Robyn Crawford's Indispensable Memoir Shows Us More of Whitney Houston Than We've Ever Seen

BooksEntertainment

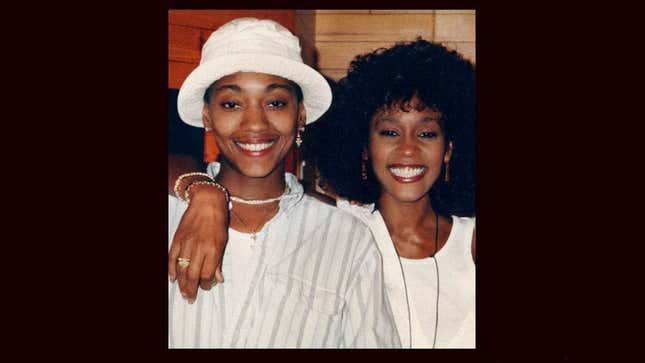

Image: Dutton

Many Whitney Houston fans never thought this day would come. Robyn Crawford, the singer’s friend, assistant, and long-rumored lover has broken her silence. As if that silence were a dam, the words pour out with a palpable fervor in Crawford’s new memoir A Song for You: My Life with Whitney Houston. This is a generous, loving book that has more insight on Houston’s career—the ride, the fall—than any other single source that I’ve encountered (it wipes the floor with the 2017 documentary Can I Be Me? and the 2018 one Whitney). Some 40 years in the making, A Song for You is unequivocally worth the wait.

The pre-release press on Crawford’s book has mostly focused on her revelation that she and Houston indeed had a romantic sexual relationship. Whispers of this virtually spanned Houston’s entire career—Crawford was a visible fixture in Houston’s public comings and goings, which set people and especially the tabloids talking—but absolute confirmation has a way of commanding attention. For the record, Crawford writes that she and Houston were intimate for about two years. It started soon after they met during the summer of 1980 working at the East Orange Community Development center. Crawford was 19; Houston would turn 17 that August. “As long as we were together, I was down for whatever,” writes Crawford, conjuring the halcyon of her young love.

In 1982, while Houston was cultivating her career in music, the singer halted the romantic aspect of her relationship with Crawford “because it would make our journey even more difficult.” They were both religious and feared damnation. They’d previously discussed Houston’s potential challenge of launching a career while in a relationship with another woman during the intolerant early ’80s. “The love I felt for Nippy was real and effortless, filled with so much feeling that when we talked about ending the physical part of our relationship, it didn’t feel I was losing that much,” writes Crawford. She remained Houston’s best friend and eventually something akin to a manager. I’ve seen “executive assistant” used to describe Crawford’s role in Houston’s career, though the label-averse Crawford writes straightforwardly about her function: “If she didn’t want you there, you weren’t getting in, at least not through me.”

The narrative is caked in cocaine and pervaded by the sweet smell of marijuana.

“Stick with me, I’ll take you around the world,” Houston told Crawford. And she did. A Song for You documents the inner workings of Houston’s career through the ’90s. It is undeniably juicy. Beyond the details of Houston’s intimacy with Crawford, there are descriptions of Eddie Murphy’s (often tepid) courting of Houston as well as the early days of Houston’s relationship with Bobby Brown. The narrative is caked in cocaine and pervaded by the sweet smell of marijuana. Crawford indulged in both alongside Houston, who told her friend that she first tried coke at age 14. It soon became clear that Houston had a problem, but A Song for You shrewdly describes the fun of getting high with Houston and going on adventures. With a sense of responsibility and nuance, Crawford examines the enjoyment she and her friend took in doing drugs in order to illustrate how they’d later become such a problem, particularly for Houston. For a time, it all seemed so innocent.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-