Why Are So Many Vogue Cover Stories Written by Men?

Entertainment

The Vogue cover story, which is to say the Vogue celebrity profile, is a very specific animal. Simultaneously fawning and enchanted by its own existence, it can sometimes approach self-parody, often knowingly, as a template of the celebrity profile and the clichés these profiles engender.

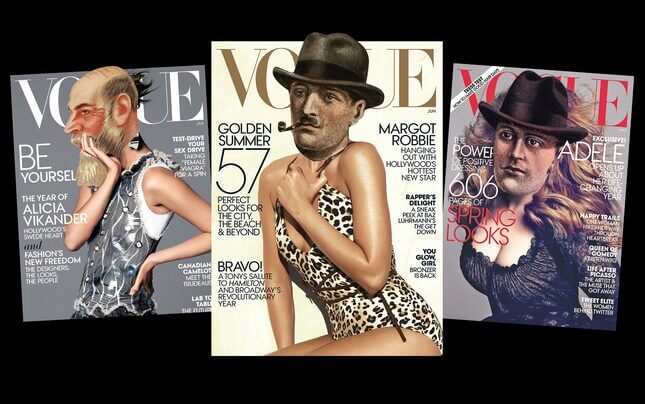

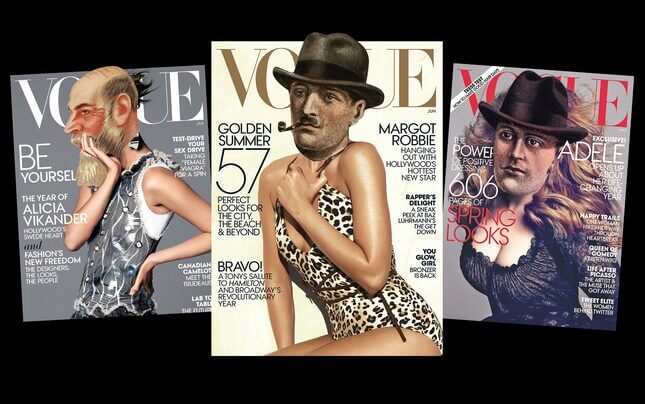

Specifically, the stock characterization of some gamine young actress pushing around salad on her plate with a fork—or scarfing a hamburger because she swears she eats!—exists partly because, often, that is what gamine young actresses are depicted as doing in Vogue cover stories. It’s a rite of passage for these cover subjects, who are usually under 40, and are exclusively women, with the exception of four men in Vogue’s history. Getting the Vogue treatment, salad/burger and all, is a specific and colossal benchmark in a woman’s celebrity. And to achieve this Vogue legitimacy means, almost always, being profiled by a man.

The most recent Vogue cover features Margot Robbie, an Australian whose career took off after she played Leonardo DiCaprio’s beleaguered wife in The Wolf of Wall Street, and who is expected to rise further after the release of Tarzan and Suicide Squad. As a beautiful young ingenue, Robbie an obvious choice for a Vogue cover in the post-2000 era, in which Anna Wintour has supplanted the supermodel cover with the celebrity (or, celebrity-who-looks-like-a-supermodel) cover. It’s been an oft-discussed decision, one that’s provoked handwringing about its effects on woman celebrities. But the TMZ industry being what it is, the Vogue cover status quo is unlikely to change; we’re lucky to get the one or two model covers per year that Wintour chooses (and even then, those models are also celebrities in their own right, like Karlie Kloss and Cara Delevingne).

What’s remained intact through the model-celebrity shift: the Vogue cover is still a milestone, a signifier of mainstream success that brings various American icons from Michelle Obama to Kim Kardashian into the same rarefied echelon. In a declining print industry, landing the cover of Vogue is one of the few measures of prestige that hasn’t wavered. And the surrealist, somewhat passé tone of the Vogue profiles is crucial to perpetuating the illusion required to make the cover such a coronation—the illusion of Anna Wintour’s fantastical universe, which casts its cover models as modern American royalty. It’s partly via that gauzy and unreal writing that the Vogue cover story gives its subjects’ most dilettantish impulses an air of legitimacy: Blake Lively’s short-lived website Preserve, for instance, which was described in a July 2014 cover story as her attempt at “using all the modern-day digital tricks of the trade to shine a light on—to preserve—all those finer, simpler things in American life that are in danger of getting touch-screened into extinction, trampled on by the medium itself.”

The Robbie cover was written by celebrity journalist Jonathan Van Meter. I’ve admired Van Meter’s work as long as I can remember—in 1993 he became the very first editor in chief of Vibe, the music magazine where, a decade after his reign, I’d later work—and he’s an accomplished writer who’s obviously made a prominent name for himself. But the Robbie story began in a way that was off, with gendered value judgments about her based on the character that made her famous.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-