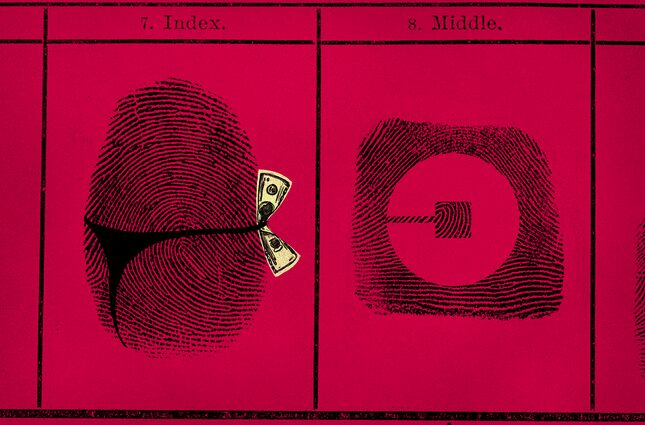

Why Are Strippers More Heavily Vetted Than Uber Drivers?

Latest

After losing an extended, expensive fight in Austin over an ordinance passed in December that mandated fingerprinting for ridesharing drivers, Uber and Lyft have ceased operating in the city. Drivers are upset about the loss of income. Riders are angry about being stuck with Austin’s insufficient cab service. Everyone is framing it in terms of crotchety, charming old Austin versus the interlopers who have either made the city one of the most vibrant in the country or killed its soul, depending on whether you moved to the city before or after Twitter exploded at SXSW.

Uber and Lyft fought the fingerprinting ordinance with Proposition 1—it was the only thing on the ballot in last week’s election—in which they asked to retain control of their background check process. They called fingerprinting an unnecessary burden on drivers and painted the city’s proposed regulations as targeted at stifling their industry. There’s also been wide speculation that Uber and Lyft are fighting fingerprinting because it could be used as fuel in employee misclassification lawsuits, like the one they recently settled in California for $100 million, which alleged the drivers were actually employees of the company and not, as Uber and Lyft say, independent contractors. (Lyft is in the process of negotiating its own settlement.)

This is a new and contrary line of thinking, because often the need to get a specialized license for work is used as evidence for the opposite argument: that a worker is an independent contractor. There are a number of contract-based professions in which workers are required to undergo this kind of background check, which has not historically led to reclassification of those workers as employees. This includes one particular profession that’s seen 30 years of misclassification lawsuits fail to change labor practices: exotic dancing.

There are many places to read about the specifics of the campaign in Austin, which brought out the worst in everyone—Uber and Lyft’s election tactics included spending almost $9 million to robo-text customers and blanket the city with paper—but I would recommend Neal Pollack’s accurately jaundiced take on my obstinate hometown. Austin, he writes, did this to itself. The city put itself in the position of choosing between a drunk driving epidemic (there were more than 6,000 DUI arrests in 2013 and 2014) and the strongarm tactics of app-based car services (the 23 percent drop in drunk driving accidents Uber claimed after it came to town was revised downward by police to 12 percent, but either way it’s significant), as its supposedly progressive residents have spent 30 years fighting against meaningful urban planning and public transportation. You say Austin’s the liberal oasis in Texas? Allow me to introduce you to the liberals who proudly protest the likes of residential density and rail lines.

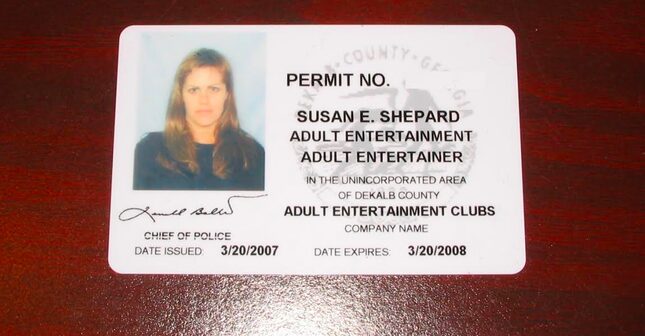

In other words, the ride-sharing companies are filling a meaningful and somewhat self-inflicted gap in the Austin market. And with all the company’s persecution fantasies, Uber isn’t wrong that licensing regulations can create a barrier to entry. Strippers, who face actual regulatory bias in many cities, understand this well. Licensing can be used to put an undue burden on people working part-time jobs as independent contractors; local regulation can be used to force out an industry deemed suspect in the name of public safety. Adult entertainment is a fragmented industry and the biggest strip club chains are a fraction of the size of Uber or Lyft, so there is no massively funded pushback against local regulations by the clubs on behalf of the workers. In cities that require strippers to obtain a license—a testament to Austin’s independence is that it’s the largest city in Texas where no effort has been made to do so—chances are they’ve been as thoroughly vetted as a cab driver. And they aren’t even responsible for driving anyone.

Stripper licensing is, like cab licensing, done on a city or county basis. There isn’t yet any state-level licensing, although Arlington state representative Bill Zedler proposed one in 2013 that would have required strippers to take a training course on human trafficking, and in 2015 a Pennsylvania proposal to create a statewide stripper registry stalled out. In both cases, the legislators were fairly transparent that they wanted to use the proposed licenses as disincentives or under the guise of protecting women from sex trafficking or working underage. Like most laws around the industry, what is touted as protecting women and children is actually about controlling women’s movements and policing nonwhites.

The licensing process in most jurisdictions only looks for drug- and prostitution-related charges and convictions. In places where the requirements are that narrow, a felony—even a homicide charge—isn’t going to disqualify someone from a stripper license, but a mere arrest on one of the specified charges can be enough to prevent the granting of a license even if the applicant was found not guilty. This means that people of color, who are more heavily policed, are disproportionately affected by licensing requirements. The City Council’s background check regulations specified that only convictions (for certain crimes, “to be specified by separate ordinance”) would be taken into account, but the Austin NAACP and Austin Area Urban League others made a similar point in a letter to the city council registering their concerns about fingerprint checks for drivers. (Currently, Uber and Lyft use third parties to run their background checks for convictions for certain offenses and moving violations.)

Of course, there are more legitimate arguments to be made for checking the backgrounds of drivers than of strippers. In Austin, investigations of sexual assault by drivers were in the spotlight, and cab drivers and ridesharing drivers alike know where their passengers live, but the worst a stripper can do is kick someone in the head with a seven-inch stiletto while popping it in a handstand. The licensing of exotic dancers is about something else, says my friend Michelle. We used to work together at an Austin strip club, and she’s also a Lyft driver. “The only reason [stripper licensing] exists is shame and revenue. It’s almost universally unnecessary,” said Michelle.

Michelle saw a lot of parallels with her experience dancing and driving for Lyft. “I found that after a few years not dancing that I really missed wrangling drunks and being out all night talking to weirdos and finding out people’s stories, and also parallel to what I enjoyed about stripping is it was a way to make people’s lives better and happier. And in the case of Lyft, it’s materially safer,” she said.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-