The Time Is Ripe for Another Lilith Fair

All-male acts make up two-thirds of music festivals, which women often feel unsafe attending. America needs a femme show again.

In DepthIn Depth

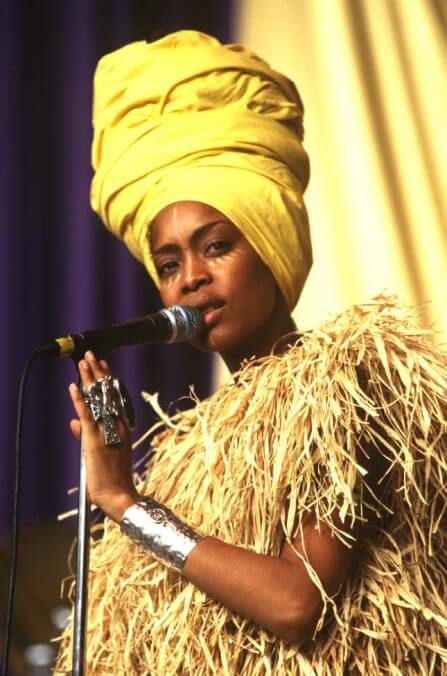

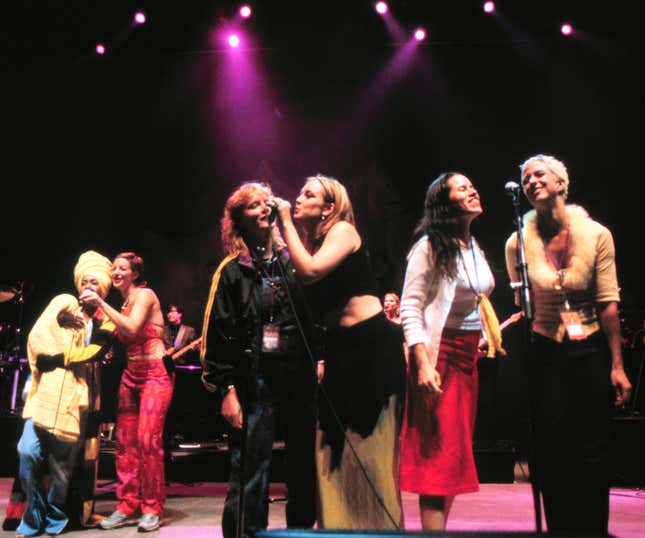

Photo: Bill Tompkins

In July 1997, Time magazine made a striking declaration on its cover: “Macho music is out. Empathy is in.” In its accompanying story, writer Christopher John Earley personified summer in America as if it was a specific kind of man, likening the months of July and August to displays of masculine mania one would’ve witnessed at an outdoor alt-rock show: “muscular bare-chested frat boys, the sharp, scabbed elbows, the clomping Reeboked feet…” But, “What if summer were different?” Earley questioned, imploring readers to imagine a more feminist season, before introducing the woman who would attempt to make it so. Her medium for performing such an onerous task? Lilith Fair, a special string of concerts that made its debut in the late-nineties and quickly became the top-grossing touring festival of the moment.

Twenty-five years later, it might be difficult to envision a summer night spent on the sprawling lawn of a local amphitheater, a space where the beer was cheap and camaraderie amongst the crowd cost even less, as a cadre of the most sought-after female and femme artists took the stage to spur a supernova the stuff of musical lore. Perhaps you don’t have to exert as much effort as someone of a younger generation. Maybe you can recall it from memory. Such was Lilith Fair.

“When you look back at the lineup, it just kind of had everyone you could possibly imagine,” music journalist and author of Her Country, Marissa R. Moss, told Jezebel in a phone interview. “It showed clearly the massive appetite for music from women, and the ability to sell massive amounts of tickets and alcohol and whatever else you need to sell to put on a profitable festival.”

The brainchild of Canadian singer-songwriter Sarah McLachlan, Lilith Fair is fondly remembered for convening the likes of the Chicks, Sheryl Crow, Queen Latifah, Fiona Apple, Tracy Chapman, and Erykah Badu, and has been credited with spring-boarding the careers of Missy Elliott, Christina Aguilera, and a host of others. Today, however, the stars of the festival might be a vinyl body-suited and booted Megan Thee Stallion, punctuating her blustering bars before a sky-high graphic reminding all to “Protect Black Women”—0r maybe Phoebe Bridgers, clad in her signature skeleton suit, would make an appearance and call the Supreme Court “irrelevant old motherfuckers” before launching into “Kyoto.” Better yet, perhaps the pair would find a way to share a set, because that kind of collaboration was ineluctable to the Lilith ether. Of course, these are only hypotheticals.

Lilith Fair abruptly ended after 1999, and though there was a mildly successful revival in 2010, canceled performers and a reported lag in sales on the heels of the recession tempered hopes for a modern run. It is unclear, when the music industry is more saturated with socially and politically outspoken female and femme artists, and the desire for the same onstage statements that almost cancelled the Chicks seems insatiable, why there hasn’t been another festival of its distinction. But, one thing is certain: The industry might not always be kind to artists who refuse to just “shut up and sing,” but there will always be a need for them.

In 1996, long before she lent “Angel” to what would become the most successful ASPCA advertisement in history, Sarah McLachlan wrote a note to folk singer Suzanne Vega, as Vega recounted in Glamour’s 2017 oral history of Lilith Fair: “I’m thinking of having a kind of girly show next year.”

As the story goes, the 28-year-old McLachlan was a success story in mid-nineties pop music, with Fumbling Towards Ecstasy, her third and most recent album, having received stellar reception. And yet, she was frustrated. The music industry was—as it remains to be—largely dominated by men: radio jockeys who wouldn’t play two female artists back-to-back, event promoters convinced that more than one woman on a bill couldn’t sell, and nationally respected journalists that didn’t cover up-and-comers. She knew they were wrong and set out to prove as much.

According to Vanity Fair’s 2019 oral history of Lilith Fair, co-authored by music critic and writer Jessica Hopper, McLachlan first conducted a test-run in 1996, playing four shows alongside fellow flourishing artists like Vega, Tracy Chapman, and Paula Cole. Inevitably, McLachlan’s hypothesis that strength in numbers sold proved substantive. Each date sold thousands of tickets and easily drew crowds with little to no promotion, from the Heartland to the Pacific coast. “People were saying, ‘You can’t do that.’ Well, we did…and people came,” McLachlan recalled to Vanity Fair.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-