Image: Chelsea Beck/GMG

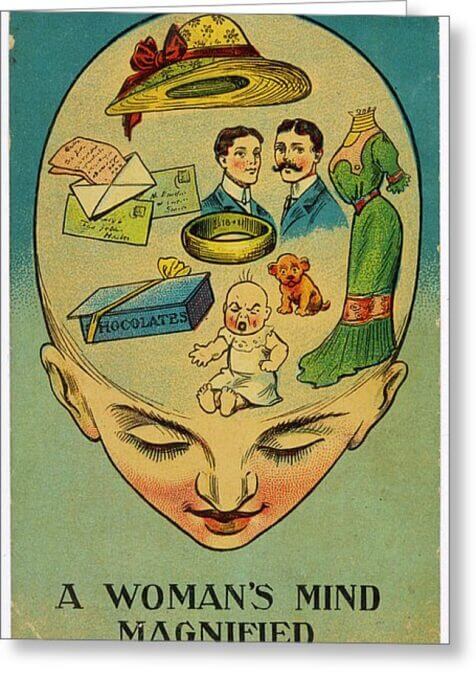

The stereotype of the incompetent, irrational woman journalist is resurgent. She is familiar and she’s bad news: she’s volatile, unethical, and not very good at her job, and she discredits anyone with a feminine-leaning identity who works for the press. Though we know by now she’s an illusion, a hoary trope in a similar vein to the Manic Pixie, she persists.

It’s hard to miss her on television. In House of Cards, journalist Zoe Barnes was often out of her depth, pulled there by her own ambition. Clever but unwise in where she placed her trust, she wound up with that frequent fate of women journalists in fiction: an affair with her most important source, followed by a gruesome death. In the original British series of House of Cards, Barnes’s equivalent was reporter Mattie Storin, who kept a writhing bundle of complexes barely contained beneath her demure, floppy-collared work suits (she referred to her much older, MP lover as “Daddy”). She, too, ends up killed off. And in HBO’s adaptation of the Gillian Flynn novel Sharp Objects, the beautiful, scarred Camille Preaker drifts into eddies of compulsion and booze as she reports on murders in her hometown.

The type pops up in literary fiction, too; the protagonist of Jonathan Lethem’s recent novel The Feral Detective describes her role at the office—in her case, the New York Times: “I’d been a decorative editorial flunky, a limit I’d never fought my way free of. (That was partly my fault, hey—it wasn’t as if I’d gone around pitching brilliant ideas for op-eds, and the witticisms that turned the heads of the men around me were more in the cause of charming self-deprecation than of carving my way out of the category of the highly dateable.)”

This enduring character type is dangerous because plenty of people believe she is real. Some of them wield global power. In a press conference on October 1, 2018, the President dismissed three reporters, all of them women. “She’s not thinking! She never does,” he was heard to tell ABC White House correspondent Cecilia Vega, before wagging his finger at CNN’s Kaitlan Collins and cutting off a third who asked a question about mass shootings. “I watch you a lot, you ask a lot of stupid questions,” he told CNN’s Abby Phillip at a press conference a few weeks later. That sentence alone could stand for how audiences as a whole have come to look at women reporters: fun to watch, ripe for tearing down. The problem has been ably dissected with an eye to what’s happening now.

The madwoman in the newsroom was first invented over a century ago. Ever since women entered the field of journalism in meaningful numbers, she had an unreliable counterpart in fiction. Leading the brigade, in The Portrait of a Lady (1881), Henry James sketched the comic character of Henrietta Stackpole, a reporter for the New York Interviewer. She is a nonconformist who hectors her friends to get married while insisting that she herself does not need a man to be happy (though ultimately, she marries). James himself admitted to Miss Stackpole’s “slightness of cohesion,” writing in his preface to the 1908 edition, “Henrietta must have been at that time a part of my wonderful notion of the lively.” In the 1908 edition, James describes Miss Stackpole as “smell[ing] of the Future—it almost knocks you down!” She isn’t a person so much as a symbol of a changing society, written by an ambivalent author who wanted to make her a figure of fun.

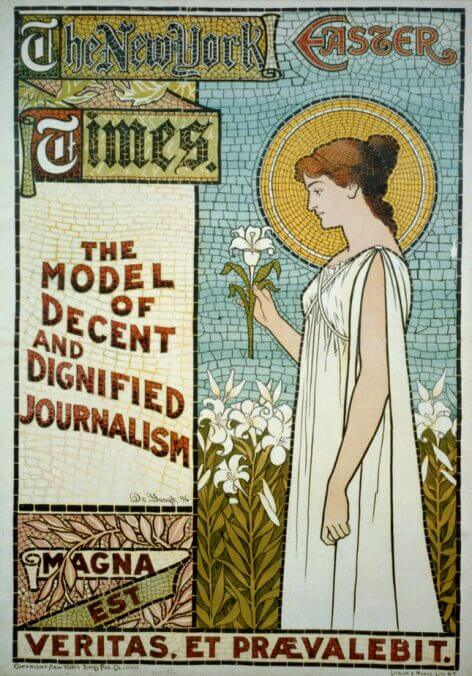

Like the insouciant Gibson Girls on bicycles who coasted across magazine covers in the Progressive Era, Miss Stackpole signaled new freedoms that were opening to women. For most of the 19th century, if educated, unmarried, ambitious “New Women” chose to work outside the home, they were expected to heed a call to a pious or caretaking vocation: missionary work or teaching. Writing and the press were less conventional options for those who weren’t drawn to these two paths, but women could and did write for the press—mostly from home, mailing in their pieces on housekeeping, fashion, and family life to editors. That changed with the groundbreaking careers of outliers including Sarah Josepha Hale, formidable editor of the required-reading magazine Godey’s Lady’s Book; transcendentalist critic Margaret Fuller; reporter Nellie Bly, famed for her undercover work; journalist and civil rights leader Ida B. Wells; and investigative magazine writer Ida M. Tarbell.

By the turn of the 20th century, journalism was decidedly co-ed. “These modern days are certainly the opportunity of the Women,” wrote English writer Ella Hepworth Dixon. “For the first time they can, and do, compete with men… One of the last citadels to fall was the newspaper office. Here prejudice reigned supreme […] Today the Bastille of Journalism has fallen.”

The reaction in fiction was swift. At best, it was anxious and picaresque, like James’s Miss Stackpole. At the other end of the spectrum, newswomen saw their careers overshadowed by affairs of the heart.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-