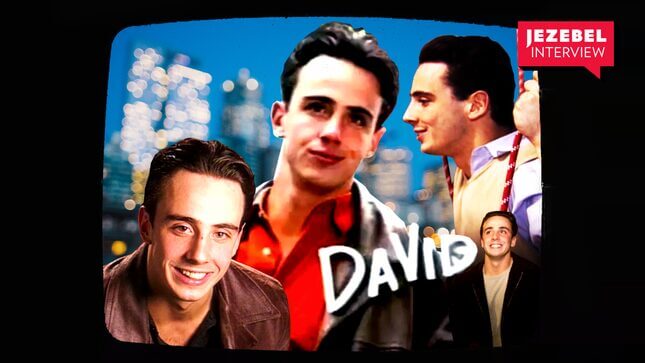

I Interviewed David Burns From The Real World: Seattle Because It’s Never Too Late to Realize Teenage Dreams

I started recording episodes on VHS, which I rewatched and rewound over and over until the tape started to skip.

EntertainmentTV

Illustration: Elena Scotti

David Burns was my first “celebrity” crush who was not a real celebrity. In the summer of 1998, as I teetered between middle and high school, The Real World: Seattle premiered and there was David with his slicked-back hair, weathered leather jacket, and multi-colored eyes (one blue, one brown). He had a penchant for black turtlenecks, which softened his raised-fist, tough guy veneer. The rest of the roommates stuck to their assigned job at a local alterna-rock radio station, while he opted for a gig at the infamous Pike Place Fish Market, unpacking seafood at the crack of dawn with a crew of surly men in bright-orange jumpsuits.

I started recording episodes on VHS, which I rewatched and rewound over and over until the tape started to skip. Then I made a fan site for him, pilfering images I’d found on MTV’s website. I hardly went outside for the rest of the summer.

I was a sheltered 14-year-old girl living in Berkeley, California with a cable TV subscription that allowed me access to the real world—meaning The Real World, meaning David, who had grown up unsheltered in a rough neighborhood in Boston. That was enough, but then came his secretive, star-crossed relationship with casting director Kira. Early on in the season, the fourth wall was knocked down when it was revealed that David and Kira, who interviewed him extensively during auditions for the show, had fallen for each other. A wrenching romantic epic ensued and my pubescent heart swelled.

here I am, a professional journalist, and an alleged adult, looking to exploit my job in the interest of realizing a teenage dream.

I’d obsessively watched all of the previous six seasons of MTV’s groundbreaking show depicting “the true story of seven strangers, picked to live in a house… and have their lives taped,” but David brought something different than previous cast members. He was a perfect archetype of the sensitive bad boy, a type I had chased throughout my feverish years of online fandom in the ’90s, which took me from Leonardo DiCaprio, with his motley crew of tortured fictional characters, to AJ McLean, the tattooed, floor-humping Backstreet Boy with the kooky facial hair, and then to David, a regular person who was neither playing a role nor performing choreographed humpage. David was part pop-culture creation, part real-life man.

Over the past two decades, I haven’t thought much about David, who, unlike many Real World cast members, did not keep chasing the reality TV spotlight. Then, late last year, I realized that he was, um, kind of a coworker of mine? He’s worked in media for years, including recently as global head of Originals & Content Licensing at Univision, Jezebel’s now-former parent company. He’s since left, but an idea was sparked. I tracked down his email and wrote to him: “Two decades ago, I ran a short-lived fan site for you. Now, here I am, a professional journalist, and an alleged adult, looking to exploit my job in the interest of realizing a teenage dream.” He gamely agreed.

Amid a flushed pubescent flashback, I spoke with David about his experience being on the other side of obsessive ’90s fandom and the lingering “what ifs” around Kira(!). More importantly, he suggested we grab a beer the next time we’re in the same city. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

JEZEBEL: What was it like for you when The Real World: Seattle started airing in 1998?

DAVID BURNS: It was a complete shock for me. I had gone on a study abroad trip to Morocco five days after we wrapped shooting. I went and lived in Fez and Marrakesh for an entire summer. I was in a different headspace. I actually kind of forgot that I had done the show. Then, when I got back, I got off the plane in JFK Airport and I was swarmed by people outside of customs. I had no idea what the fuck was going on. My buddy Charlie was standing next to me going, “What’s going on?” I’m like, “I don’t know!” We literally ran out of the airport.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-