Like what you just read? You’ve got great taste. Subscribe to Jezebel, and for $5 a month or $50 a year, you’ll get access to a bunch of subscriber benefits, including getting to read the next article (and all the ones after that) ad-free. Plus, you’ll be supporting independent journalism—which, can you even imagine not supporting independent journalism in times like these? Yikes.

Rape, Revenge, and Writing

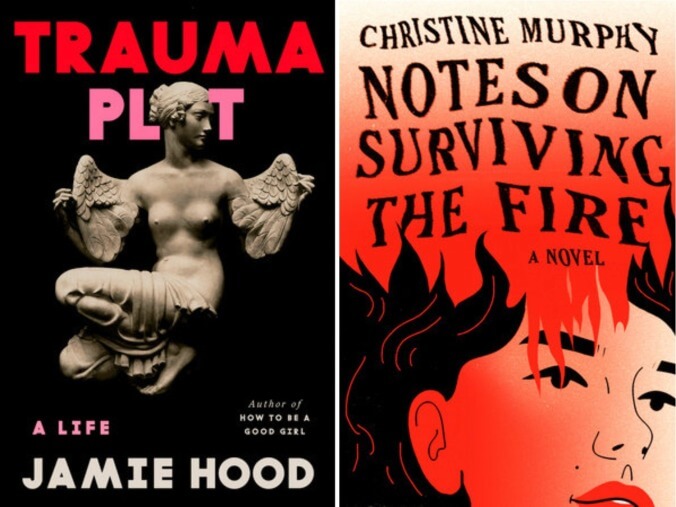

Trauma Plot by Jamie Hood and Notes on Surviving the Fire by Christine Murphy explore how women process and forge new senses of self in the aftermath of assault.

Photo: iStockphoto Books

In the introduction of her memoir Trauma Plot, Jamie Hood invokes the ancient Greek legend of Philomela. After Philomela, a princess, is raped by her brother-in-law Tereus, she threatens to talk, after which he cuts out her tongue. Though Philomela later has her revenge, her literal silencing has echoed in stories of rape victims throughout the subsequent centuries, both in art—Shakespeare referenced Philomela in Titus Andronicus, for example—and, inevitably, in real life. In the myth, Philomela manages to tell Tereus’ wife what has happened by weaving her story into a tapestry; later, his wife kills their son and feeds him to an unknowing Tereus as punishment. But Philomela, who is turned into a nightingale, never entirely escapes what has been done to her, and the story culminates in violence and despair.

Though women now can speak about being raped more than Philomela could, doing so remains difficult, and the criminal justice system offers little recourse to victims. Over two-thirds of rape victims in America choose not to report their rapes to the police, no doubt because so few rapes are prosecuted, and even fewer (below 1%) yield convictions. Those who do speak up are routinely treated with hostility and skepticism: As Rebecca Solnit observed in Men Explain Things To Me, “When a woman says something uncomfortable about male misconduct, she is routinely portrayed as delusional, a malicious conspirator, a pathological liar, a whiner who doesn’t recognize it’s all in fun, or all of the above.” Anyone who has witnessed stories of rape and abuse unfold in public in our post-Me Too culture can attest to this pattern: female victims are routinely demonized, while men tend to escape unscathed.

Without reliable recourse to either the criminal justice system or the court of public opinion, victims are left to find ways to heal on their own. As the fable of Philomela illustrates, talking about these experiences can be difficult or complicated, and it can be tempting to view the aftermath of a rape as a catastrophe from which escape feels impossible. As the philosopher Susan Brison writes in Aftermath: Violence and the Remaking of the Self, she found talking about her rape difficult: “I was never entirely mute, but I often had bouts of what a friend labeled ‘fractured speech,’ during which I stuttered and stammered.” But when a survivor can find that voice, the taboo act of speaking—or writing—about the experience of rape can shift power from the rapist, and a society full of complacent bystanders, to the victim.

Pantheon, Knopf

By this logic, both Trauma Plot, in which Hood recounts multiple episodes of rape and their aftermath, and the novel Notes on Surviving the Fire, in which Christine Murphy crafts a thriller out of the epidemic of campus rape, are acts of reclamation. In both, the authors use the craft of writing to reframe their personal narratives (Murphy is, like Hood, a survivor) and to pose moral questions about violence, revenge, and the self in the wake of violation. Trauma Plot is primarily concerned with the reconstitution of the self in the wake of trauma, while Notes on Surviving the Fire asks how a rape victim can continue to live as an ethical person in a world that aids and abets rapists—that is, in a world where ethics no longer seem to apply.

After being raped by a fellow member of her PhD cohort, Sarah, the narrator of Notes on Surviving the Fire, is dismissed by local police and ostracized by many in her academic program. Though her rape has shattered her life, its effects would be much less overwhelming if her university, UC Santa Teresa (a fictional campus), provided support to students who have survived sexual violence. Instead, it takes students years to qualify for group therapy through UCST, and when they finally get there, they mostly discuss the university’s Kafkaesque Title IX process, rather than their initial traumas. Though Sarah’s PhD cohort has heard about her accusation against her rapist, they have chosen to tacitly ignore it; her rapist has faced no consequences, and Sarah must continue to work in the same department with him. Meanwhile, like every other PhD student in America, Sarah is also struggling financially. Her advisor is unresponsive. Southern California, where UCST is located, is on fire. And, as the book opens, her best friend Nathan is found dead in his home.

Though the police dismiss Nathan’s death as a straightforward overdose, Sarah is convinced that he has been killed. He never used heroin, and although he was left-handed, the needle was inserted in his left arm. Sarah begins to suspect that her rapist’s bumbling but frightening best friend, whom she calls Flopsy (her rapist is referred to only as Rapist) had something to do with Nathan’s death. According to Nathan’s diary, Flopsy had aggressively pushed him into a wall, and he later tells Sarah that “Nathan got what he had coming … and I don’t feel bad about it.” The two pairs of students had been at odds since Sarah reported Rapist for raping her, and when Sarah finds a stash of heroin under Flopsy’s bed after breaking into his house, her suspicions grow stronger.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-