“Outwit, outplay, outlast,” could be the slogan for pretty much any game that’s designed to break down relations between its players. But it’s particularly pertinent as the tag line of Survivor, a reality competition that—much like Jumanji, without any of the magic or knife-throwing monkeys—has always been played at the expense of the participant.

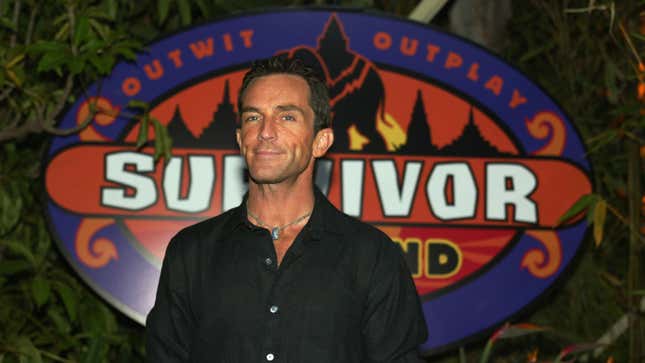

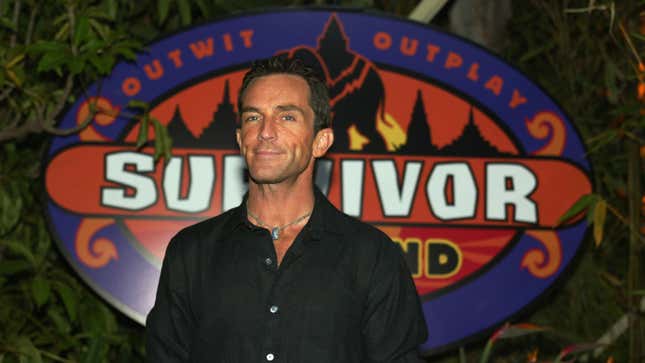

Survivor, a show that bred a new, hyper-competitive form of reality TV—and has been hailed by critics as “the biggest game-changer in the past 20 years of television”—is, in essence, a showcase of resilience. “You are witnessing sixteen Americans begin an adventure that will forever change their lives,” host Jeff Probst said in a voiceover, introducing Season 1. The adventure Survivor promised viewers was traditional: contestants marooned on a desert island face playground challenges like walking through fire, building shelters from scraps, and starting fires with their hands. What viewers were actually witnessing, though, was a live experiment that rewarded those contestants who were unwaveringly able to play the dirtiest game for the sake of money.

So perhaps the sexual harassment allegations that have disturbed the most recent season of Survivor shouldn’t come as much of a shock to longtime viewers. This season, a group of contestants took the machiavellian gameplay that’s synonymous with the Survivor brand and expanded it to the kind of sexual harassment that’s increasingly not tolerated in an era of MeToo. In the eighth episode of Season 39, Survivor cast member Kellee Kim accused Dan Spilo, a player and Hollywood talent agent, of repeated unwanted touching over the course of filming. Kim reported that the incidents occurred both while she was awake and while she slept. Producers reportedly issued Spilo warnings about his behavior and didn’t address Kim’s allegations until a member of the crew also reported experiencing a similar interaction, at which point Spilo was dismissed.

The manipulative behavior

The manipulative behavior, meanwhile, worked as intended. After two other cast members, Missy Byrd and Elizabeth Beisel, formed a false alliance by fabricating their own complaints against Spilo, Kim was voted off during a tribal council ceremony. (Byrn and Beisel later apologized for weaponizing sexual assault in order to progress in what is, at the end of the day, a fucking game show.) After the incident involving a member of production, Spilo was also ejected from the island.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-