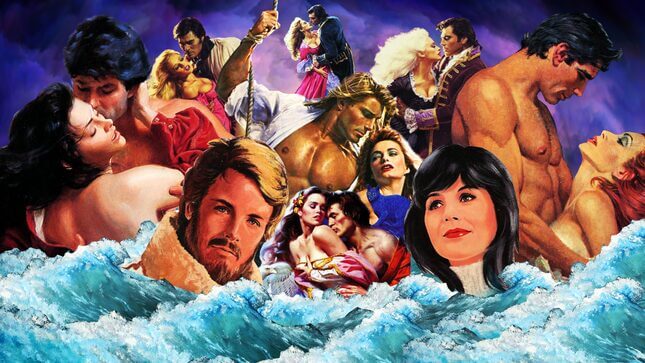

Graphic: Elena Scotti/GMG

“We’ve got some books here I want to show you,” Johnny Carson told a Tonight Show audience in March 1990. He turned to a colorful stack of paperback romance novels.

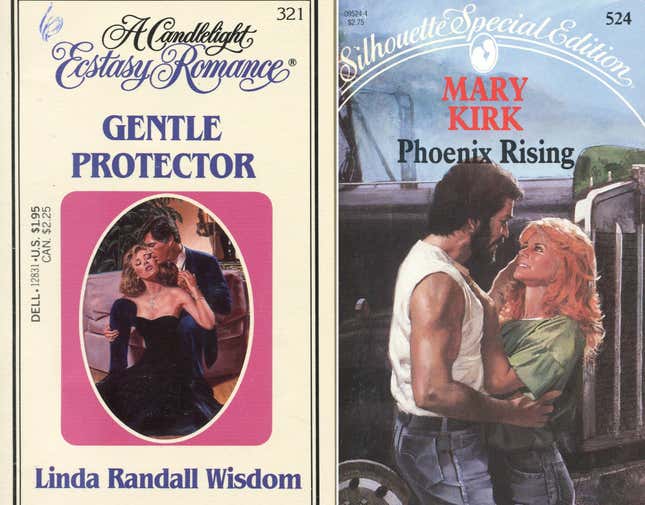

He explained that you usually find these books in supermarkets; “They say the biggest type of reader of these type of things are ladies,” he informed his viewers and sidekick Ed McMahon. Carson began to hold them up, one by one: “You see that?” The camera cut in close to show The Lion’s Lady by Julie Garwood, featuring a blonde with her head thrown back as a dark, handsome man nuzzles her neck. Then came Elaine Coffman’s Escape Not My Love, which he opened to what’s known as the “step-back,” a glossy, lush, full-color interior cover featuring a couple locked in a passionate embrace. Here, it’s a dark-haired woman swathed in a generically 19th-century lavender gown erupting with frothy lace, being nuzzled by a blonde Adonis, the pair horizontal on a pink satin surface, an enormous floral arrangement behind them.

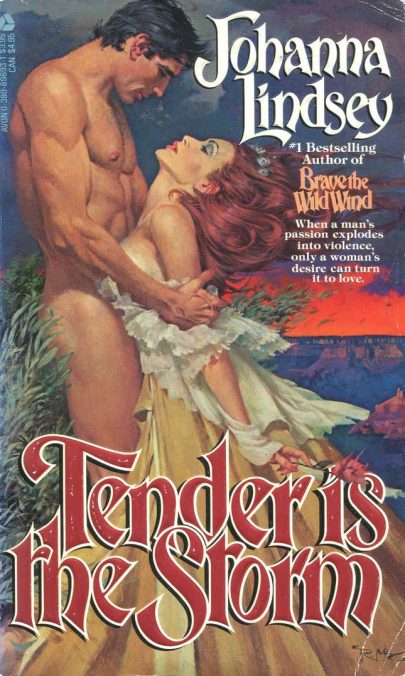

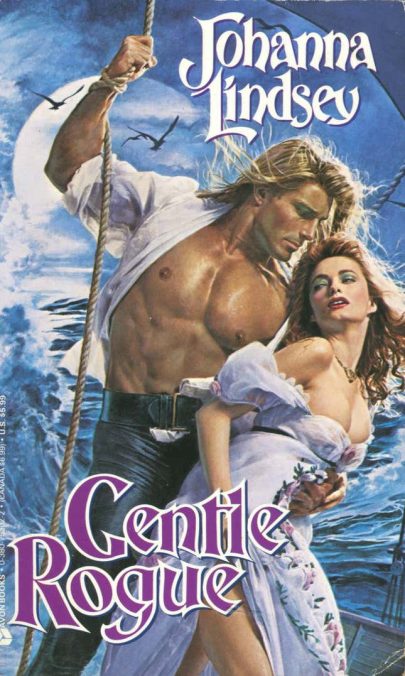

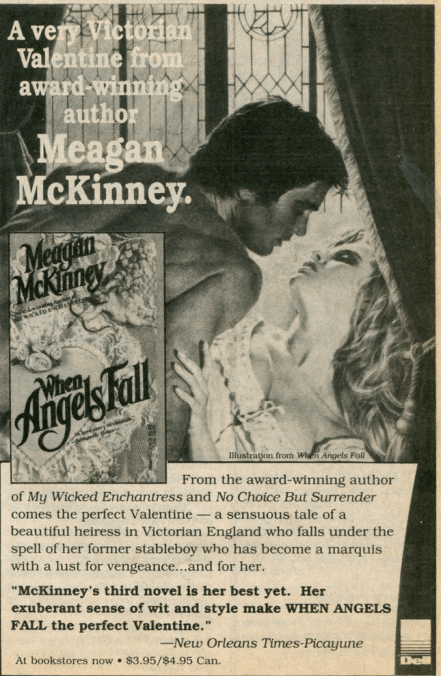

“See, this gives you an idea of what it’s like,” said Carson. “Now you’re talking!” replied McMahon. “The guys are always bare-chested and so forth,” said Carson, proceeding to Megan McKinney’s When Angels Fall with a couple tumbling across a bed—she’s about to burst out of a chemise, he’s wearing tan pants that show off his butt, there’s another vase full of roses nearby—pronouncing it “steamy stuff, folks.” Finally came the grand finale: Savage Thunder by Johanna Lindsey, then one of the genre’s most popular authors. “You know any of these people?” he asked McMahon, who replied that he did not.

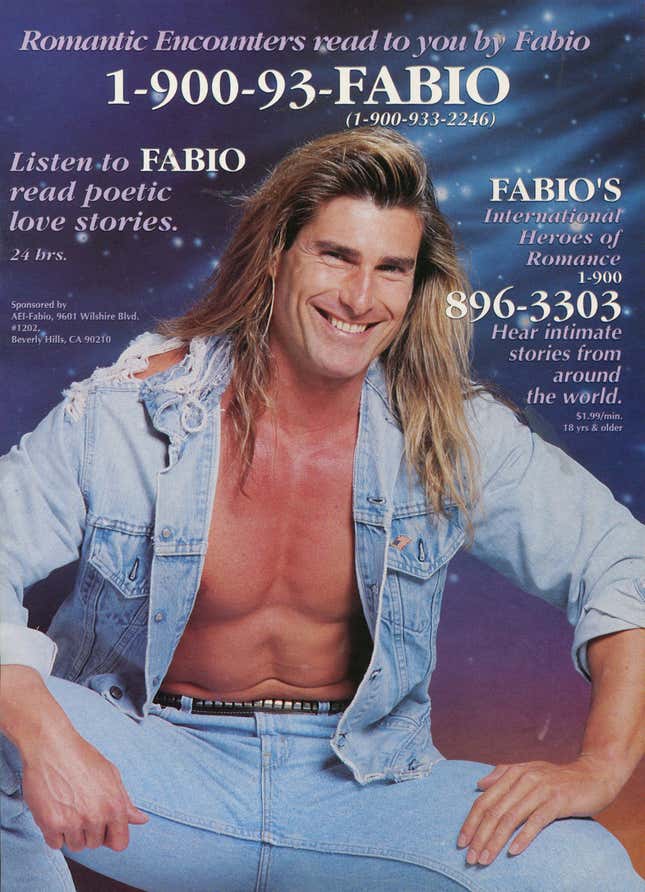

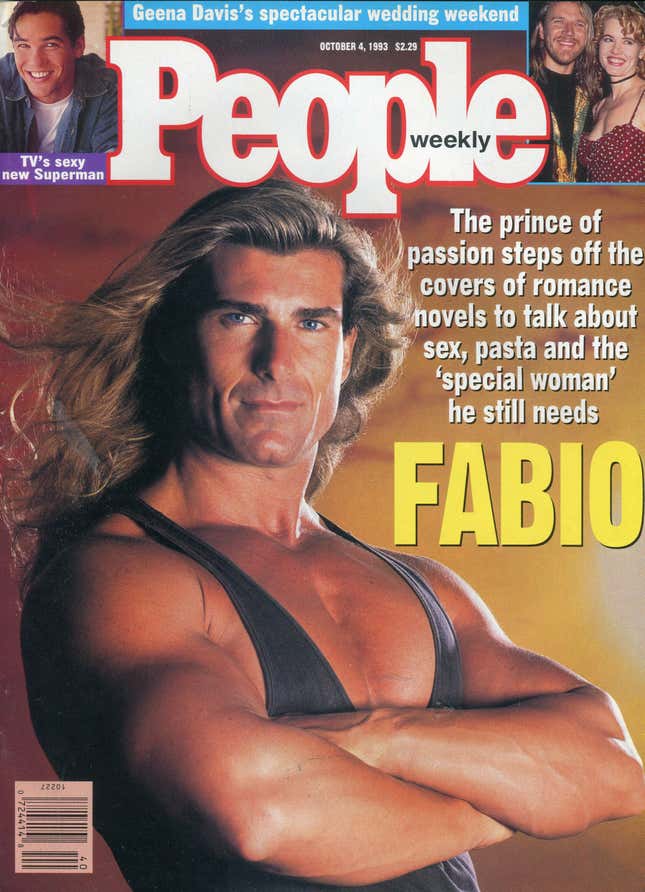

“Look at the cover on this baby,” Carson said, flipped the book outward to outright hooting and hollering from the audience. The cover featured a bare-chested young model named Fabio, hair blowing in the breeze, a redhead en borderline déshabillé at his feet and clinging, beseeching, to his open leather vest. Carson didn’t read any of the back-cover copy, or flip through to any of the quotes—the covers said it all.

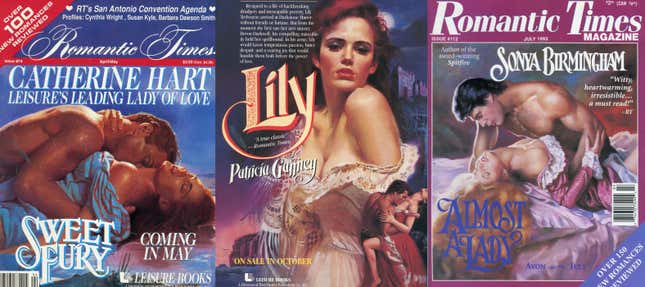

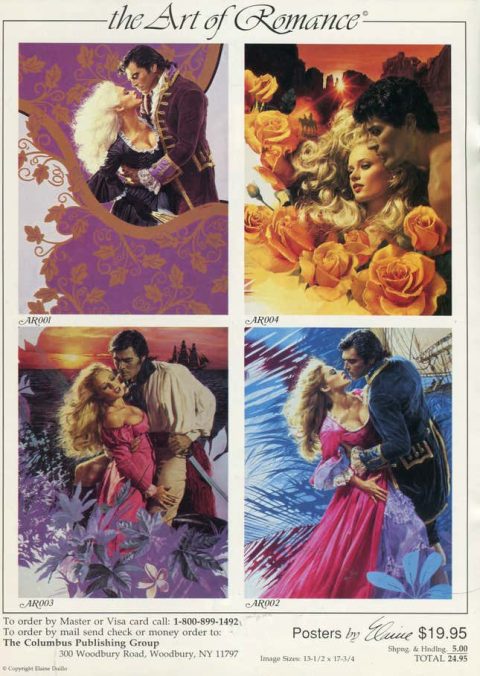

In a way, Carson and McMahon were right: The covers did quite deliberately indicate that there was steamy stuff inside. No popular genre is as firmly associated with its packaging as romance novels; even Playboy is given constant credit for its best journalistic years. For decades, coverage erased any differences between covers and content, and the genre has long been synonymous with a specific style of art from a specific period.

As the 1970s opened, the look of romances was tame, reflecting the fairly chaste contents of the books themselves. Sex scenes were closed door, or at least incredibly light on detail; any jollies to be gotten came in the form of the infamous “punishing” kisses.

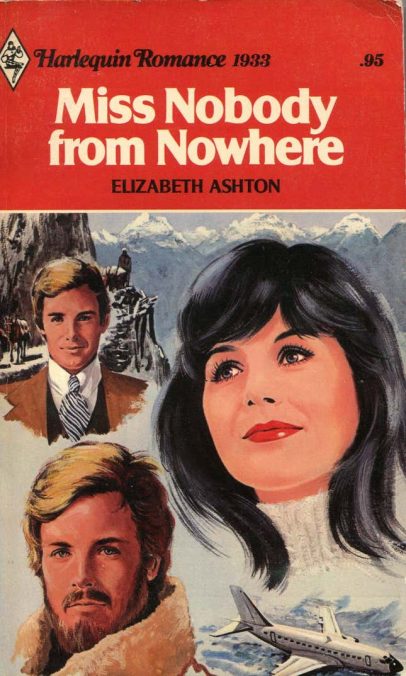

Speaking to Publisher’s Weekly in 1974, Bantam art director Len Leone described his approach like so: “I try to make my romances look like little white candy boxes,” he told the trade publication. “Flowers on the cover, a piece of sweet but simple art in a pretty shape on the box.” The market at the time was dominated by short, contemporary-set stories and practically synonymous with the publisher Harlequin. Their style tended to be pulpy depictions of men and women staring moodily into the distance, perhaps with some Alps behind them. Generally, these storylines featured naive young girls paired with inscrutable older men who didn’t reveal their emotional cards until a declaration in the last pages.

But the actual storylines of the books underwent a sea change after the publication of The Flame and the Flower by Kathleen Woodiwiss in 1972 and Sweet Savage Love by Rosemary Rogers in 1974. Rogers’s and Woodiwiss’s success proved that women would buy sweeping epics featuring explicit, often violent sex. These new storylines required new packaging, and the covers began to dramatically change.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-