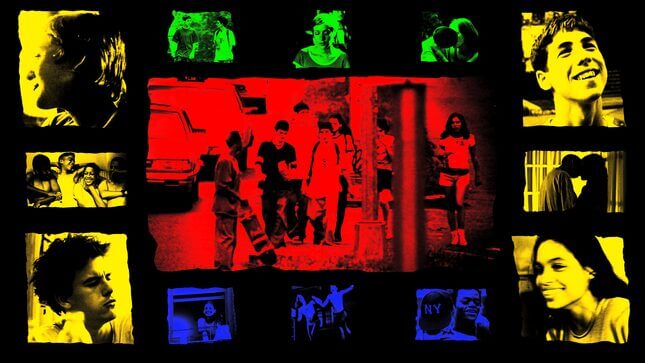

Illustration: Array

The 1995 film Kids is one of those projects that stays active in your mind long after you’ve watched the end credits roll. Following the lives of a band of misfits living in New York, and shot with the unpolished lens of a documentary, it touched on the blissful ignorance of youth and the unsettling prevalence of peer pressure—all framed within the context of the AIDS pandemic that was devastating the American healthcare system. Directed by photographer Larry Clarke and written by Harmony Korine, who would later write and direct Spring Breakers, the film was a star-making vehicle for a young Rosario Dawson and Chloë Sevigny. It also made celebrities of the skateboarders featured heavily as marauders of the city who were constantly up to no good.

Reactions to the film were explosive and polarized, with critics applauding (through gritted teeth) the realism of teenage self-destruction, while others found it salacious and wildly exploitive. In the 25 years since its debut, cast members have spoken of the film, both the creative process and the ways it shaped their lives. Notably, an air of unease has followed Kids, making it somewhat of an acclaimed but eerie success story in indie filmmaking. Two cast members, Justin Pierce and Harold Hunter, died relatively young after battling drug addiction and depression, and Leo Fitzpatrick, who played the lead role of Telly, has spoken of being accosted and harassed in the streets by viewers who truly believed he was the same menace to society he portrayed in the film.

For co-producers Christine Vachon and Lauren Zalaznick, jumping on board was a no-brainer after reading the script. Vachon, the winner of both a Gotham and an Independent Spirit Award, was a short film veteran when she started working on Kids alongside Zalaznick, with the two having forged a successful working relationship after meeting right out of college. Kids is a standout part of Vachon’s creative oeuvre that has seen her produce films like the Academy nominated Far From Home, I Shot Andy Warhol, and the Oscar-winning Boys Don’t Cry. Zalaznick is most known for her work in the reality television industry-leading hits Project Runway and Top Chef.

Aside from working together on Kids, the pair also co-produced the sci-fi drama Poison, Swoon (a cinematic retelling of the relationship between murderers Nathaniel Leopold Jr. and Richard Loeb), and the 1993 short Dottie Gets Spanked. I recently spoke with Vachon and Zalaznick about the making of Kids, its zeitgeist appeal, and how it still stands apart decades later.

JEZEBEL: What first drew you to the film? Was it the cast, script, director, or a little bit of everything?

CHRISTINE VACHON: Well, it came to us as a script from Red Hot, which was an organization that came together to do various productions to benefit people with HIV. The most famous one they did was a series of cover bands covering Cole Porter music. They wanted to do more and the woman who ran it (Leigh Blake) showed Lauren and me the script. There was no cast attached to it; it was Harmony and Larry, and they knew they wanted to cast the film mostly from a group of kids who skateboarded at Washington Square Park. We really got involved, I would say very quickly after the script was written. Is that your recollection, Lauren?

LAUREN ZALAZNICK: It is. And in terms of what drew us, it’s an overused word today, but the script was absolutely fresh. It was not trying to be anything it wasn’t. It was definitely, in my recollection, the [type of] script which just leapt off the page. It was probably secondarily the way that Harmony and Larry had this vision for these kids who they described in Washington Square Park. Christine and I were really very connected to that area. Our office was right near there, I lived right near there. It was brought to life in the script and then through Harmony and Larry and then through the actual cast as we either met them or during the casting process.

So then you were both pretty hands-on during the creative process?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-