‘Why Not Us: Southern Dance’ Makes the Case for Black Dancers as the Original Influencers

The women of HBCU dance lines have long shaped mainstream pop culture. The ESPN+ series returns to give them the hype and credit they're owed.

In Depth

Kayla Pittman, an alumna of Louisiana’s Southern University and a professional dancer featured in Beyoncé’s Homecoming, is somewhat of a celebrity among HBCUs (historically Black colleges and universities). Her dance style has been described as “milky,” though it’s hard to accurately capture the silky refrains and sharp shifts in words. The oozing texture of honey comes close, but then again, honey lacks Pittman’s bravado. Perhaps words escape because the way Pittman sews, stitching together delicacy, sexuality, and hip-hop in one routine, is a singular product of Southern University and the organization that made Pittman the dancer she is today: the Fabulous Dancing Dolls.

Steeped in nostalgia and femme-presenting poise, the Dancing Dolls, arguably the most prolific and widely known amongst university dance lines, are the subject of the new series Why Not Us: Southern Dance, premiering on August 11 on ESPN+. Southern University is featured in the third season of Why Not Us—executive produced by NBA player Chris Paul—which chronicles the beauty and influence of HBCU culture. The second season featured Florida A&M University’s football team, and the show now finds itself in mirrored rehearsal rooms where Dr. Akai Smith, the coach of the Dolls, must assemble a team of athletes who comprise HBCU lore in their own right.

While Why Not Us: Southern Dance closely resembles the competitive edge and high emotional stakes of Netflix’s Cheer, its focus on the deeply embedded Black artistry in HBCU culture—and, really, popular culture at large—is without modern-day comparison. Just as the heroes of any sporting league win the affection of fans and daydreamers alike, the young women at the center of this show will quickly earn the respect and adoration of viewers. But this time, unlike many dancers before them, they won’t be chronicled as a gimmick or a sideline distraction. They’re the main event.

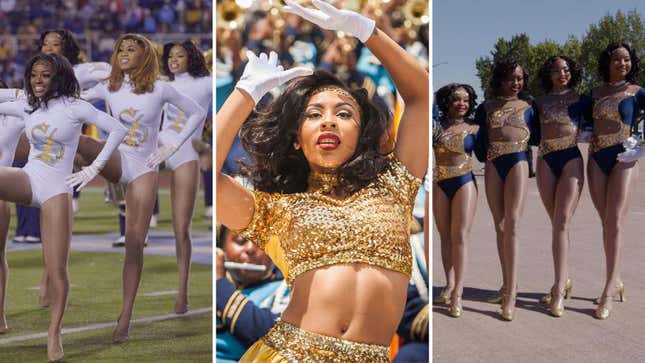

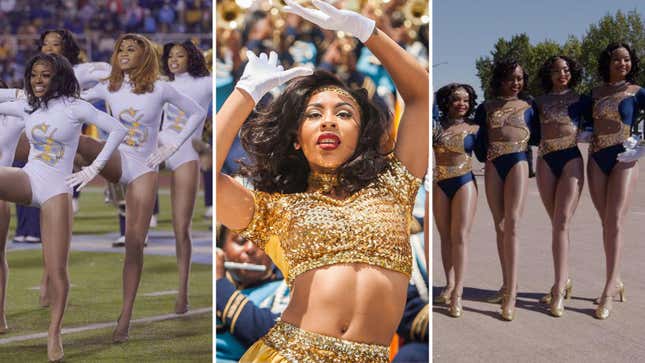

Viewers are greeted with a perfume cloud of captivating stage presence, cropped white gloves, leopard print leotards, and glittery capes. The Dolls are an elaborately coiffed presentation of Black hyper-femininity, literally “dolled up” in high-waisted briefs and feather-bedazzled bra tops. Not a single forced smile to be found. But the women are also regarded as athletes and are initiated into an extreme, pressure-cooker environment in which the prospective Dolls put their childhood dreams on the line, hoping to join the ranks of the best HBCU dance line.The women of HBCU dance lines have long been setting pop culture trends, but are only just beginning to garner the widespread attention, hype, and credit they deserve. Beyonce’s 2018 Coachella performance and accompanying Netflix documentary Homecoming brought the attitude and command of hip-hop majorettes and dance lines to the forefront of musical culture. Lizzo has featured the Dancing Dolls in music videos filmed on HBCU campuses. And Dancing Dolls alumna Kiara Ely went on to perform in and co-choreograph the Nick Cannon film Drumline; danced alongside iconic artists like Nicki Minaj, John Legend, Missy Elliott, and Lil Kim; and choreographed stage performances for Ciara, Janelle Monae, Ludacris, TLC, and Christina Aguilera. But misogynoir around Black feminine aesthetics have downplayed and ignored the outsized influence these artists have on mainstream culture.

“Everyone always says that this team must be influenced by something, but I always provoke people to think about us being the influencers. The Dolls are not just a group of girls that are pretty, they’re not just what you see on Saturday,” she said. “These girls are so talented that I would do them a disservice by saying that they’re influenced by Black culture. They are the influencers. Dance is really just the platform that opens them up to a world of being successful women, and ultimately, that is Black culture.”

For all the force and ease with which Smith, the coach, commands a room of ambitious women in their teens and early 20s, she is, in no way, a camera person. “Anybody that worked on the show with me knows that every time you turn around, I was trying to run from the camera,” she told Jezebel in a phone interview. But that certainly doesn’t stop her from becoming an endearing, forward-facing character in the series, or from trumpeting her pride for the “Black girl magic” of her dancers.

“People today want to know what it’s like to attend an HBCU, what the experience is like, what Black culture is like, the dance teams and the marching bands,” she said of the recent fervor to lionize HBCUs, the first of which was established in 1837. “The trend is ongoing, and everybody now wants to have a piece of it.”

HBCU dance lines emerged in the 1960s, a natural evolution from the majorettes or baton twirlers who performed alongside each school’s marching band. By the ’70s, the already rich culture around homecoming halftime performances—with its camp, fringe, and sequins—was enlivened by the emergence of dance lines, whose style combined classic marching techniques with “lyrical, West African, jazz, contemporary, and hip-hop choreography,” according to BuzzFeed’s Frederick McKindra. While some schools adopted the hip-hop-based “bucking,” the Dancing Dolls ushered in what McKindra calls an era of smooth, balletic, and “prissy” movements, famed for “slow body rolls,” graceful attitude leaps, and stand counts in the bleachers.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-