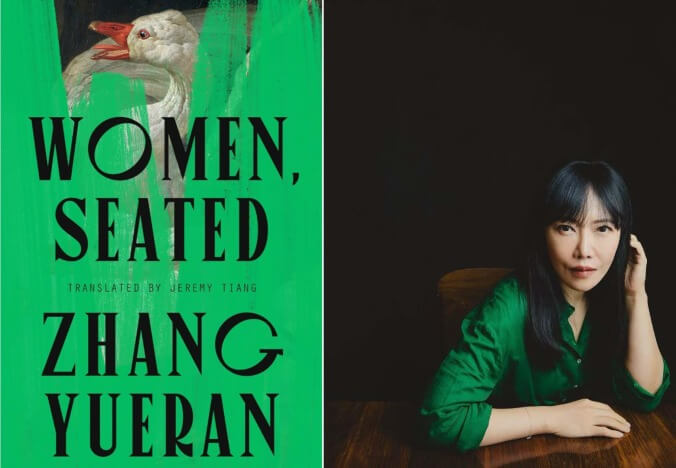

‘Women, Seated’ Shows How Precarity, Wealth, and ‘Having It All’ Are Not Just American Problems

Zhang Yueran’s new novel is part of a wave of Asian authors breaking the dominance of Europe in translated literature in the U.S., while dissecting gender and class in their respective societies.

Photo: iStockhphoto BooksEntertainment

In Zhang Yueran’s new novel, Women Seated, Yu Ling, a nanny to a wealthy family in Beijing, yearns for a more independent life, one where she can marry her boyfriend and leave her cold employers forever. Yet like so many other nannies across the world, Yu Ling can’t help but love her charge, 7-year-old Kuan Kuan. In turn, Kuan Kuan is devoted to her in a way he is not to either of his parents: “He liked holding on to [Yu Ling’s] ear as he dozed off, and when he couldn’t sleep, he’d kneed her earlobes with his plump little fingers.” She is his security blanket.

Yu Ling’s world is thrown into chaos when the government arrests Kuan Kuan’s maternal grandfather. After Kuan Kuan’s father is also arrested, his mother, Qin Wen, disappears, and Yu Ling finds herself the temporary mistress of the house in which she was previously a servant.

But it’s not freedom she feels: She remains bound to the house and to Kuan Kuan as a result of her emotional attachment to him.

Despite her love for the boy, Yu Ling is keenly aware that their bond is a result of her employment, and that it will be altered if and when Qin Wen reappears and reasserts her role as his real mother. Though Yu Ling was at first eager to work for Qin Wen, an artist, in her studio, and then happily took on the role of nanny for Kuan Kuan, their relationships are altered when Qin Wen learns that Yu Ling has a criminal record back home. When Yu Ling tries to resign, Qin Wen replies that she’ll have to keep working for them no matter what: No one else will hire her given her background. Yu Ling had “always believed she’d chosen to work for this household, that she’d chosen to give her affection to Kuan Kuan. … Now she realized she was trapped, a pathetic person who needed to be taken in.”

However, whether or not she gave her affection to Kuan Kuan willingly or as a result of coercion, she now cannot help caring for him.

Qin Wen is also ambivalent toward her work. She is dedicated to painting, but has faded into obscurity. Unlike many women artists, Qin Wen is not overwhelmed by the burden of childcare, but as a result of her marriage. She was able to pursue her artistic goals thanks to a wealthy, politically connected father, but the benefits of this wealth came to feel corrupting. Her domineering husband, who married Qin Wen for her money, insists she ought to have a solo show, but his support feels more like an exercise in status than in artistic expression. “He’d bring in a highly experienced curator from abroad, book the finest gallery, invite the most prominent people … make sure all my paintings sold in no time at all,” she tells Yu Ling. But “the whole thing felt meaningless. … The only reason they’d buy these paintings would be to curry favor with my father or husband. Who would want that kind of appreciation?” Qin Wen feels trapped in her marriage and her life, and her depression at being unable to create meaningfully is legitimate. But Zhang also understands that only people who do not need to worry about money have the luxury to dwell on the frustrations of having too much of it.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-