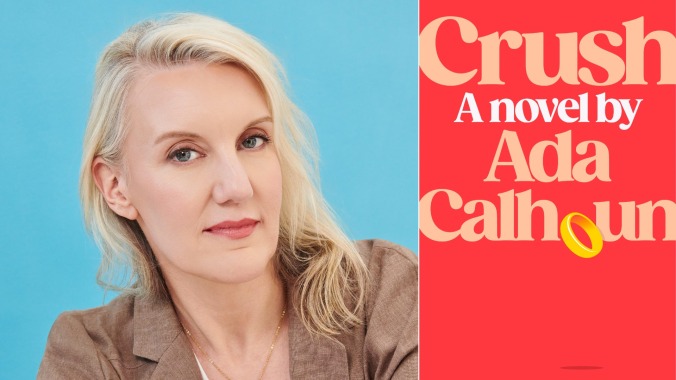

Ada Calhoun’s New Novel Is About Flirting, Lovers, and a Woman Figuring Out Her Own Way

"The first few men who read it were like, 'This book is very sad,'" she says of 'Crush.' "Not a single woman has said that to me. Almost every woman who has read the book was like, 'This was joyful.'"

Photo: iStockphoto BooksEntertainment

“You really should put down the Transcendentalists and read Polysecure,” advises Paul, the protagonist’s husband in Ada Calhoun’s new book, Crush. After Paul admits he’d enjoy being with someone other men want, the unnamed narrator is given a free pass, and she ends up in an unexpectedly intense situation with David, an old college friend-turned-lover—the titular “crush.”

She tries to compartmentalize it as a fling, but their giddy long distance correspondence—which involves round-the-clock ultralong emails with footnotes and multiple languages—reveals the true nature of whatever’s happening between the two of them. It’s not so much the type of polyamory that’s taken the stylish coastal media by storm (see the numerous articles on the subject over the past year or so, mostly in publications with “New York” in their name); instead, the narrator somewhat accidentally ends up with two partners. “I tried to think of myself as Archie and these two men as Betty and Veronica,” she says, wishfully, of Paul and David.

Paul becomes impatient with his wife’s connection, and their clashing visions about evolving their couple become untenable. Her core traditionalism—about clinging to the promise of longevity within her marriage—can feel anachronistic, and increasingly wearisome, as she has clearly moved on but refuses to acknowledge it. Ultimately, Crush explores when to realize a partnership has reached an impasse, and when to take yourself on a new adventure.

We spoke with Calhoun—a native New Yorker and prolific writer of both novels and nonfiction—about slight incredulity surrounding open marriages, feminist liberation from familial obligations, and refraining from trying to force personal relationships into a tidy narrative.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

The narrator glancingly mentions this “swirl” of open marriage articles and books. How much were you thinking about this cultural discourse as a backdrop?

The idea for the book is that she’s trying to figure out how to keep both these men in her life. She’s looking at every possible solution throughout history. Included in that wealth of literature are all these articles coming out online, and books. They’re these potential resources for trying to figure out this thing that’s extremely difficult—to say, “We’re going to flout centuries of what it means to be faithful to someone and what it means to be a good partner, and we are going to come up with something completely new.” It is very audacious, but a lot of people are motivated to do that in every era.

There’s something about it now that I think is coming out of the pandemic. It dismantled all of these systems: Suddenly the rules are not the rules. You don’t go to the office every day, you don’t send your kids to school all the time. These things that we thought were the way things were, that were unchangeable, were suddenly very changeable. A lot of people were suddenly questioning everything. I saw that especially with women, and it makes sense to me that almost all the articles and books I’m seeing are by women saying, “wait a minute.”

Headshot: Jena Cumbo

Do you feel Crush is in conversation with those books and articles?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-