How a $5 Pack of Abortion Pills in Ethiopia Sparked a Movement to ‘Demedicalize’ Access in the U.S.

In her new book, Access, Rebecca Grant chronicles activists' decades-long fight to defy abortion restrictions—including the origin story of Plan C.

Photo: Getty Images AbortionBooks

This is an excerpt from Access: Inside the Abortion Underground and the Sixty-Year Battle for Reproductive Freedom, by Rebecca Grant. The book chronicles activists’ decades-long mission to defy abortion restrictions and fight for reproductive freedom, from the U.S. to France, Mexico, the Netherlands, and more.

In 2014, Elisa Wells and Francine Coeytaux were positioned outside a pharmacy in Ethiopia waiting for a colleague to come out. The pharmacy was sandwiched between two stores with green signs that read “Fujifilm Digital Print Shop” and set back from the bustling red-and-yellow sidewalk. A few moments later, their companion, a woman, emerged holding a box. White and light brown with a yellow rose and branded as a “Safe-T” kit, its label read: “This pack contains treatment for early medical abortion.”

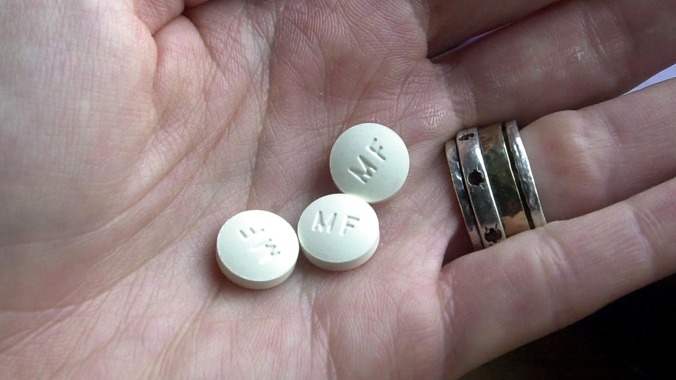

Wells and Coeytaux were stunned. There they were in the Ethiopian highlands, in one of the poorest, most health-challenged countries in the world, and people could walk into a pharmacy and buy a combination pack of abortion pills, including mifepristone and misoprostol. In the United States, FDA regulations only allowed mifepristone to be dispensed within the confines of a clinic, medical office, or hospital, making it no easier to access than surgical abortion; it wasn’t available in pharmacies, nor could it be sent in the mail, even by certified prescribers. Also, there were no “medical termination of pregnancy” (MTP) kits, also known as “combipacks,” available in the US, in which the appropriate dosages of mifepristone and misoprostol were packaged together in one blister pack, as was available elsewhere. (American patients received each of the two medications in separate packaging.)

Moreover, a medication abortion in the US cost around $500–600, while the kit the woman was holding, with generic versions of the same medications, had cost around $5. That was expensive by local standards, but the gap in price was still hard for Wells and Coeytaux to wrap their minds around.

They were part of a team for the MacArthur Foundation evaluating projects that used misoprostol to treat postpartum hemorrhage in sub-Saharan Africa. Observing the availability of medication abortion kits in the region— how available they were, how relatively easily they could be obtained directly by patients, how the distribution of the medication was community-based instead of rooted in a medical system—threw into sharp relief how not just burdensome but also superfluous the hurdles were in the US.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-