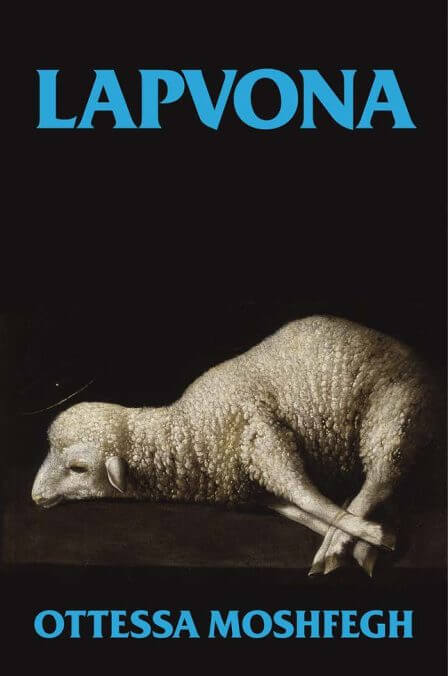

Ottessa Moshfegh’s ‘Lapvona’ Is the Feel-Bad Hit of the Summer

The response to the brazenly unpleasant Lapvona is as divisive as it gets for a contemporary book. This is a good, good thing.

BooksEntertainment

Could it be a coincidence that Ottessa Moshfegh’s brazenly unpleasant new novel, Lapvona, was released on the first day of summer this year? I can’t imagine that it is. The timing works in deadpan harmony with the book’s content, a seemingly medieval-set story that marries gory fairytale vibes with contemporary cynicism over a society that is on its way to hell, if not already charred by flames lit from within. The idea of this grotesquerie—in which abuse and humiliation are the norm, and cannibalism, degradation, human starvation, and rape are key features—being someone’s beach read isn’t funny haha, per se, but it strikes such an ironic image as to be hilarious. It’s like noticing a deflated eggplant pool float hanging out of the mouth of the great white shark that is barreling your way.

The book is so pungent with suffering that an ocean breeze would do nothing to mask its misery. It’s not just the gore—the dismemberment of a corpse to feed a hungry witch during a plight; the flapping eyeball on the dead body of a teenager. It’s not just the abuse—the lord of the setting Lapvona, Villiam, has a servant pelted with a grape that’s been rubbed on an asshole for his entertainment in a shit-dark comedic scene that would have fit well into Pier Paolo Pasolini’s de Sade adaptation Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom. The book is difficult beyond its gag-reflex testing proclivities. A shifting third-person point of view thrusts us into the minds of some dozen characters, often within the same scene and sometimes within the same paragraph. I haven’t read a book this in love with its own omniscience since Frank Herbert’s similarly shifty Dune. It’s as though Moshfegh, who until Lapvona had written her novels in the first person, just discovered a new super power and is eager to show it off. What if the mass thought-sharing capabilities that Twitter allows were grafted onto old-timey feudal living? What if God was one of us?

What if the mass thought-sharing capabilities that Twitter allows were grafted onto old-timey feudal living?

In Lapvona, Moshfegh surveys the selfishness at every level of the social ladder and throws up her hands. Sometimes all you can do is laugh, right? Lapvona is as rigid as a burlap shirt but unfolds like a soap opera, regularly rolling out new reveals. (For that reason, some of the plot points discussed in this review could be considered spoilers.) The effect of these somewhat discordant sensibilities is to electrocute any notion of a high/low culture divide. As prim as the novel can be, it is almost devoid of pretense. The characters say what they think, or if they don’t, we get to read their thoughts anyway. There’s an uncommon focus on dreams, which seem to be inconsequential to the plot, insofar as the book has one (the overall effect is more like observing Moshfegh play with the literary dolls she just cut out). Moshfegh, whose last book, 2018’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, found her protagonist largely unconscious, shares a surrealist’s fixation on the dream world. Visual artist Louise Bourgeois once said that “the surrealists made a joke of everything. And I consider life a tragedy.” Moshfegh’s wry depiction of human misery suggests that those two world views need not be mutually exclusive.

The book’s ostensible protagonist, 13-year-old disabled peasant Marek relishes his father’s abuse in a manner that sometimes takes on an erotic, masochistic bent (“He, too, enjoyed the pain, and he was ashamed of that”) but mostly derives from piety (“Marek was heartened by his father’s renewed disdain, as this made God love him more through pity”). Because we can read other characters’ thoughts, we get to see them call bullshit on each other. “Villiam thought Marek’s waking martyrdom was a kind of barbarian vanity,” writes Moshfegh. Villiam, meanwhile, hires bandits to terrorize the poor people he rules over and plunders their resources (“Terror and grief were good for morale, Villiam believed”). He hosts an eating competition while the people of Lapvona starve and when he is presented with his dead son, he asks with a chuckle, “Is that an eye hanging out?” The forest-dwelling witch Ina is a wet nurse for the village—but to mitigate any potential selflessness one might suspect derives from her service, nursing actually restores the blind woman’s sight temporarily. No one in this book thinks for very long outside of their own self interests. Moshfegh has long been fascinated by the disgusting products of human bodies, and in Lapvona egocentric thinking is presented as the body’s most unseemly function.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-