Complicated Women: A Trans Daughter’s Eulogy for Her Mother

Tossed around and neglected in childhood, I forged a new path forward with my mother when she began fighting for my existence.

In Depth

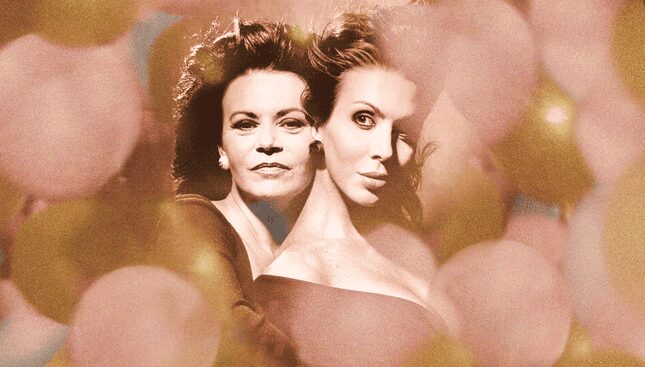

Graphic: Christina D’Angelo

It is early May and already the pollened haze is ambering the seats of every pair of riding breeches in town. The mallets at the Whitney Polo Field whack throughout the morning, and by lunch the Carolinian humidity is so heavy it threatens to bend all the Lacoste collars at the Green Boundary Club.

“Oh, sure, Aiken’s a gracious town for the haves,” Mother used to say, “but the have-nots get the pleasure of being looked down on by horse portraits at the McDonald’s. This town makes me fucking sick.”

After equestrian events, the old-money set and Yankee parvenues pile into the grand lobby of the Willcox, which, as every article about the hotel is compelled to mention, “is known to locals as Aiken’s living room”—although Mother said she’d “never heard that shit before in my entire life.”

From the late ‘60s to the mid-’80s, the Willcox was a shuttered ruin, and for curious kids of lesser means, the subject of endless fascination. We’d ride our bikes up to the porch and peek through the broken windows into the crumbling lobby that had seen FDR rendezvousing with “that Rutherfurd woman” and even the bent neck of a socialite’s mutt weighed down by the 45-carat Hope Diamond. The inn was reborn to her former splendor in 1985, its roaring fireplaces again reflecting on the baby grand and ice clinking in highballs. Five years later, when I was just 25, I returned to Aiken to host Thanksgiving dinner in its wood-paneled dining room. I sat at the head of the table, flanked by grandparents and aunts and uncles who barely batted an eye when they learned that I had recently finished my final surgery. With Mother by my side, they didn’t dare act otherwise. “Christina is my daughter now, and that is that,” she told my great-grandmother, “pass the biscuits, please.”

And now, decades later, my friend Angela and I have flown down from New York on an evening in May and checked in for three days.

The sun is dipping behind the centuries-old magnolias as the valet whisks us up to our rambling suite, where the staff is setting up for tomorrow’s gathering in our private dining room with floral arrangements and champagne buckets.

It’s not the event I expected to come back to South Carolina for. Instead of celebrating her birthday over styrofoam cups full of peach cobbler at Dukes Bar-B-Que, Mother was being wheeled into an oven at a crematorium in North Augusta on the day she should have turned 69.

At sunrise I take the tray of toast and coffee into the powder room, place it on the vanity, brace myself against the basin, and exhale: I don’t know how to do this. How do I eulogize the five decades I had with my mother in only two anecdotes? There are plenty of options, though few are fit for public consumption.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-