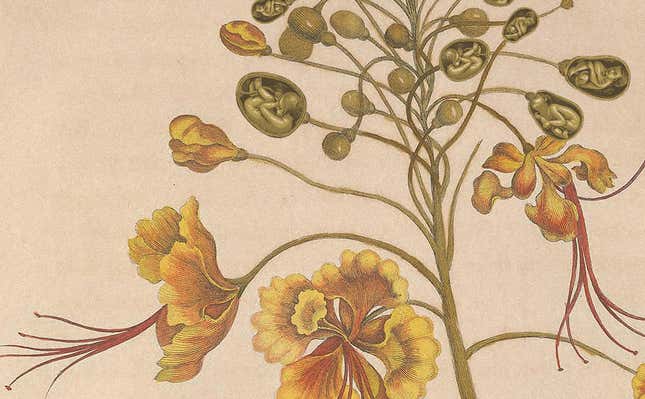

The peacock flower (or flos pavonis) is an arresting plant, standing nine feet tall in full bloom, with brilliant red and yellow blossoms. But it’s more than beautiful; it’s an abortifacient, too. One of the most striking records of the plant comes from German-born botanical illustrator Maria Sibylla Merian who, in her 1705 book Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam, recounts:

The Indians, who are not treated well by their Dutch masters, use the seeds [of this plant] to abort their children, so that their children will not become slaves like they are. The black slaves from Guinea and Angola have demanded to be well treated, threatening to refuse to have children. They told me this themselves.

Merian wrote this account after traveling to Surinam, then a Dutch colony, for the purpose of recording the country’s plants and insects. She had hoped to make a major discovery by uncovering a plant like quinine, which had made both planters and botanist rich. In the early eighteenth century, applied botany was big business. Advances in the field had opened a new world of medicines. But Merian made no such discoveries, recording instead the little-valued knowledge of slave women whose use of the peacock flower was deeply political.

She wasn’t the first to describe these qualities. Two other naturalists had also discovered the peacock flower’s use as an abortifacient in the West Indies. Michel Descourtilz, a Frenchman, had observed its same use in Haiti, writing with disdain of the “ill intentions of the ‘negress’ who aborted their offspring.” Another remarked on the “guilty practice of preventing pregnancy by use of herbs” and was surprised that slave women used them effectively, that the “drinks did not destroy health.”

Merian’s own account of the peacock flower is a vast departure from her contemporaries and a truly remarkable record. Though short, her description ascribes rationality to the act of abortion which, in the hands of Surinam’s slave women, is an act of resistance: a reclamation of their bodies and reproductive processes—neither of which, by legal standards of the eighteenth century, they owned. Equally striking about Merian’s description is the plainness of her language, her open usage of the word “abortion,” and the directness of the plant’s illicit uses. Merian does not moralize about the usage of the seeds: she simply conveys what other women have told her.

But the most fascinating thing about Merian’s revelation about the peacock flower was its total lack of dissemination within European medical communities. Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam was widely used by both botanists and men of medicine—so much so that intact copies today fetch incredibly high prices. And the peacock flower itself came to Europe: merchants valued the plant’s looks and shipped large numbers of its poisonous seeds to their home countries, where the flower decorated nearly every royal garden.

Outside of Merian’s book, however, there was virtually no mention of the abortive qualities of the peacock flowers.

While the scientific revolution and colonialism aided the discovery numerous medicinal herbs, Europe collectively engaged in a kind of culturally induced amnesia of abortifacients. Londa Schiebinger, a feminist historian of science, notes: “The same forces feeding the explosion of knowledge we associate with the Scientific Revolution and global expansion led to an implosion of knowledge of herbal abortifacients. European awareness of antifertility agents declined over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.”

The story of the peacock flower is a microcosm of a larger history of abortifacients: knowledge passed from woman to woman, often outside the boundaries of traditional medical discourses and, therefore, forever confined to a moral realm of danger and superstition. But despite hundreds of years of legal and religious repression, the abortifacient endured, proving that the desire for reproductive freedom is not nearly as modern as some argue.

The history of abortifacients is a narrative that parallels and informs our own contemporary debates over them, particularly in the wake of the Hobby Lobby decision. It’s a history that has always been mired in the murky waters of what exactly an abortifacient is; what constitutes life, and when does it begin? But it’s also a story of the incredible flexibility of legal systems that found ever-new and astonishing ways to suppress reproductive freedom.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-