The White Editors of 'Rage Baking' Overlooked the Black Woman Who Popularized the Term

Latest

On the surface, the idea of “rage baking” seems commonplace enough: You’re livid about something; you bake it off. But if you’re going to publish a politicized cookbook on how “baking can be an outlet for expressing our feelings about the current state of our society,” you might want to give credit to the person who brought the term into the mainstream.

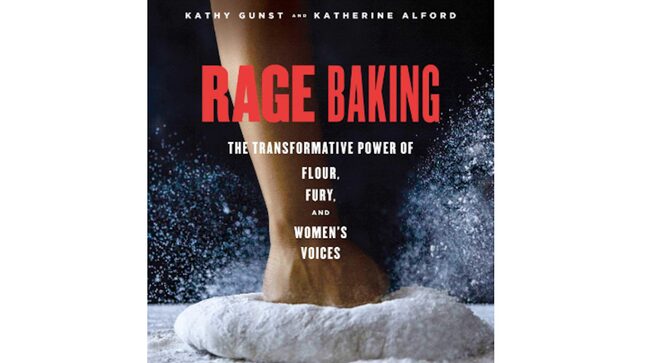

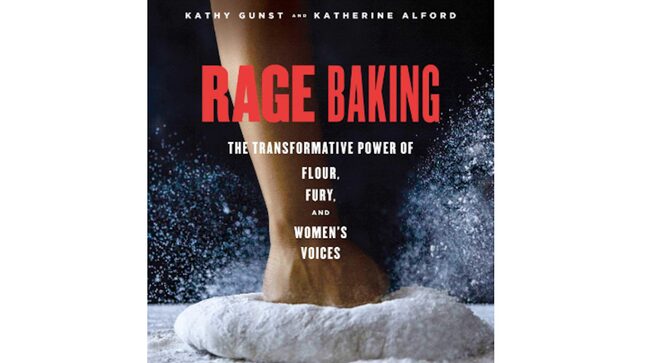

Earlier this month, Simon & Schuster released a cookbook called Rage Baking: The Transformative Power of Flour, Fury, and Women’s Voices. It was edited by Katherine Alford, formerly of the Food Network, and NPR’s Kathy Gunst, and includes contributions from a wide variety of food industry professionals as well as writers and artists. The description encourages women “to use sugar and sass as a way to defend, resist, and protest.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-