Neko Case Is Not Nostalgic, but Her New Memoir Is All About Growing Up

Case’s stunning new book doesn’t follow the typical music memoir path; instead, she told Jezebel, it’s “more about the feeling of creativity.”

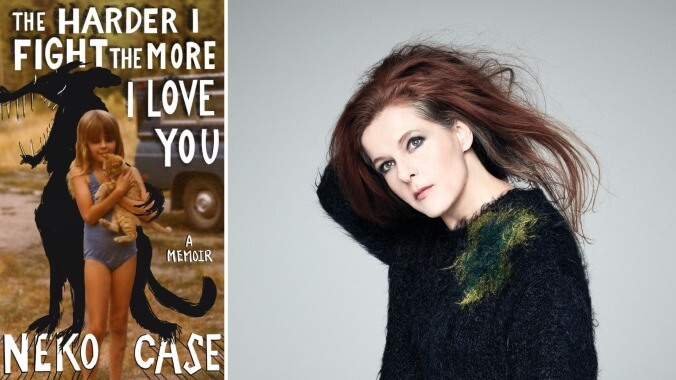

Photo: Grand Central Publishing, Emily Shur EntertainmentMusic

Neko Case was always a storyteller, even if her stories were often not autobiographical. The singer is known as a member of the Canadian power-pop heroes The New Pornographers—and also for her acclaimed solo albums.

Throughout Case’s 30-year career in music, she’s made herself into many characters and spun myriad tales from varying perspectives; her songs often contain as much detail and prose as some novels. Take her point of view as a sage narrator on the song “Margaret vs. Pauline” off of her breakout album Fox Confessor Brings the Flood, comparing the lives of the privileged, “cool side of satin” Pauline to the tragic Margaret who “lost three fingers at the cannery.” On her next album, Middle Cyclone, Case reifies her passion as a vengeful tornado tearing through a country town on “This Tornado Loves You.”

It is no surprise then that Case is just as adept an author when the focus is on herself. Her new memoir, The Harder I Fight, the More I Love You, started as a project in the early days of the pandemic for an alternative stream of income when the future of the economy—and especially that of the music industry—looked bleak. Instead of the novel she intended to write, her publisher expressed interest in Case revealing a previously unseen, more-intimate side.

If you are expecting the same old music memoir from Case, The Harder I Fight…, much like its author, does not capitulate to anyone’s expectations. It is not a play-by-play about writing and recording her albums; rather, it’s a look into the events that make Case both the person and artist we adore today. The chill of growing up in the Pacific Northwest’s wet winters is palpable in her writing, as is the pain of growing up with poisonous family dynamics—including the story of when her mother faked her own death. Music and Case’s own determination are the common threads she holds onto, and she manages to pull herself out of the grief in the end.

Despite the heaviness of her memoir, Case was warm and witty when we met on Zoom earlier this winter. We discussed her writing process, her upcoming album, and her work on an upcoming (and until recently, secret) Thelma & Louise musical due to open in 2026.

The memoir is stunning. It’s such a good read. I ate it up in like, two days. How did this get started?

I didn’t intend to write a memoir at first. I was approached by Grand Central to write a book, but I wanted to write fiction. Then they suggested I do this first, saying “We’ll pay you for your own stories.” I figured I needed the work, it was early in the pandemic, so they got to me. I hadn’t considered writing a memoir before, but I wasn’t upset about it or anything. Obviously, it worked out.

You were publishing on Substack for a bit—more day-in-the-life stuff that I assume fed into writing a memoir. What did you get out of writing the memoir that you didn’t usually get out of your songwriting or your Substack?

I’m a Virgo, and I like to compartmentalize things. So it was helpful to have my memories all in one place that. I know that seems really simplistic, but writing the book felt really organizational in a very satisfying way. I mean, I was a mess with highlighter pens and Post-Its all over the apartment. Even with my Virgo obsession with organization, we Virgos are secretly really sloppy. We are just dying to be Capricorns.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-