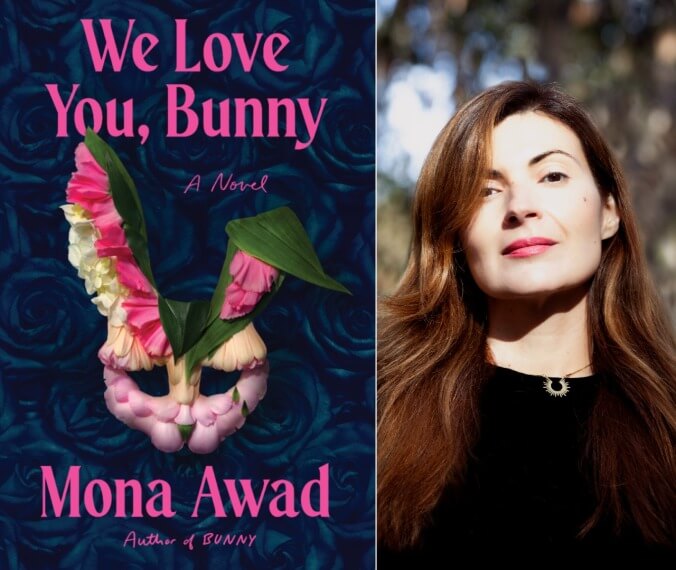

‘We Love You, Bunny’ Is Stranger and More Ambitious Than ‘Bunny’

Mona Awad's new novel is a "Frankenstein" for 21st-century MFA students.

Photo: iStockphoto BooksEntertainment

Mona Awad’s new novel, We Love You, Bunny picks up where Bunny (2019) left off: Protagonist Sam has extricated herself from the clutches of the rest of her MFA cohort, a group of women who transform rabbits into desirable men, setting the stage for this not-quite-a-sequel sequel. Told in part from the point of view of Sam’s nemeses, the Bunnies, We Love You, Bunny also includes the point of view of Aerius, the first bunny they transformed into a man, who is hell bent on escaping the Bunnies’ clutches. Much stranger and more ambitious than the original, Awad’s new novel pulls apart academia and the nature of creativity itself.

Awad, a Canadian writer who received her MFA from Brown, enjoys challenging the status quo: academia in Bunny, beauty standards in Rouge (2023), health in All’s Well (2021), and gender in all of the above. In all three books, her heroines lose touch with reality and yearn for something bigger and better than their lives; they succumb to cults in Bunny and Rouge, and to the lure of magic healing in All’s Well, which features her protagonist miraculously cured of her chronic pain. Awad’s gifts shine in her chosen tropes, but she’s occasionally failed to thoroughly interrogate the toxic environments in which her characters operate. While Rouge critiques the overwhelming whiteness of the beauty industry (drawing on Awad’s partial Egyptian heritage), Bunny is oddly silent on race and sexuality. The Bunnies, though hilariously awful, don’t really resemble real MFA students: It’s unusual these days to find an all-white MFA cohort, and I’ve never met a writing student, let alone four, who dresses like a princess or speaks in such cloying tones. While this makes a perfect environment to isolate Sam in the novel, it doesn’t resemble any kind of reality.

Photo: S&S/Marysue Rucci Books, Angela Sterling

We Love You, Bunny draws on Awad’s strengths while expanding her repertoire. Showcasing the Bunnies’ points of view is fun; as cult leaders, they are not all-knowing but instead sniping and pathetic. While her attempts to diversify her characters are mostly superficial (a few references to race and some sexual tension between the Bunnies), this new novel is richly creative. Bunny, in the world of the new book, is a novel Sam has written and is promoting. Unsatisfied with the fact that Sam’s novel is her perspective, the Bunnies (leader Elsinore and followers Kyra, Coraline, and Viktoria) kidnap Sam and force her to listen to their side of the story, focusing on the first year of their MFA, before Bunny (the real novel, and also Sam’s fictional novel) takes place.

This meta choice of Awad’s is deeply amusing. She pokes fun at Bunny; the Bunnies themselves are far from impressed by Sam’s depiction of them, and Awad has a sense of humor about her own use of tropes. And now, instead of presenting as a uniform force, the Bunnies are constantly at odds with each other, jostling for status. However, the thing they can all agree on—back in the first year of their MFA—is that their male professor, Allan, has treated them outrageously. Enraged by the mere concept of constructive feedback, they describe his critiques as “assault.” Their collective, impotent anger leads them to imagine a beautiful, compliant man who would validate, rather than criticize, their work. This man, they fantasize, would “no[d] at everything she fucking said, she was so endlessly fascinating.” Through this inadvertent act of spell-casting, they turn a bunny into a man for the first time. Unlike their subsequent attempts—which Sam observed in Bunny were physically slightly off and incapable of having sex—this man, Aerius, is a perfect Adonis.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-