It’s Hard to Pull Off a Memoir About Hating Men When You Won’t (or Can’t) Write About Your Famous Ex

Anna Marie Tendler's Men Have Called Her Crazy lacks context and self-reflection, which are key elements of a memoir.

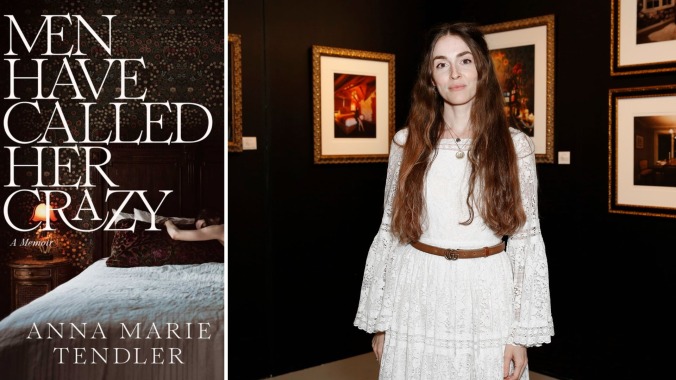

Photo: Simon & Schuster, Rachel Murray/Getty Images

Many times while reading Anna Marie Tendler’s new memoir, Men Have Called Her Crazy, I found myself thinking (and writing in the margins), “girl, pull it together!!” But it wasn’t a plea for her to quell her anxiety or stop dating men who display more red flags than a barrier island beach at rip tide. No, it was me begging Tendler’s ideas and anecdotes to coalesce into a thesis beyond blanket, basic hatred of men.

Most pop culture followers were introduced to Tendler through her ex-husband, comedian John Mulaney, who developed a reputation as a “wife guy” and spoke lovingly of Tendler in his standup specials. So when they split in spring 2021, following Mulaney’s 60-day stint in rehab, it was a bit shocking. At the time, the two revealed very little about the details of their split—save for Tendler’s statement: “I am heartbroken that John has decided to end our marriage.” Her fans’ spears were further sharpened when Mulaney was very shortly thereafter linked to Olivia Munn (they are now married) and Munn gave birth to their son in November 2021. At minimum, it’s an eyebrow-raising timeline.

Men Have Called Her Crazy sheds a little more light on that chronology. “My marriage was falling apart” following covid lockdown, Tendler writes. (In a 2023 essay for Elle, she explained, “Petunia [her dog] and I moved to Connecticut in December 2020, in the wake of my severe mental health breakdown and what appeared to be the impending end of my marriage.”) But that is the extent of Mulaney-related insight in her memoir, save for a brief mention of attending Al-Anon (Mulaney is open about being a recovering addict), and Tendler writing, “I am embarrassed to admit [my financial situation is] made stable by the security of my romantic partners.” (Similarly, Mulaney made no mention of Tendler in his first comedy special after their divorce.)

Writing around Mulaney is no small task and one that, ultimately, I don’t think Tendler successfully executes. His omission, for whatever reason (some people speculate there’s an NDA), begs the question of what else readers are supposed to glean from this book. The unsatisfying answer Tendler provides are tales of her two-week stay at an in-patient psychiatric hospital in January 2021 and recounting formative romantic and family relationships through her youth to early 20s. Those anecdotes themselves are, at times, insightful and relatable, but the memoir as a whole feels more like following stray yarns that never quite get woven into a fully fleshed out tapestry.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-