The 2019 Pro-Life Women’s conference wasn’t in New Orleans as advertised, but in the adjacent suburb of Kenner, where there are more strip malls and significantly fewer temptations to sin. The Pontchartrain Convention and Civic Center, isolated in a lonely corner of the city, sat at the end of a slab of concrete with all the square footage and charisma of an airstrip. It was a summer weekend between the Great Southern Gun and Knife Show and the Gumbo Dance Sport Championship, the heat so intense that dragonflies were plunging mid-flight and flopping around on the pavement like fish. Outside the glass building, a middle-aged woman perspired into a cigarette and wondered aloud whether the dying insects were simply missing their queen. Turning from the insects, she gazed idly across the street at the only other feature of the landscape, two linked barricades protecting the designated “Protest Area.” No one was there.

Had any protesters decided to brave the humidity, they would have found something between a talk show and a medical panel, the kind of sentimental, performative huddle usually reserved daytime television. Four gynecologists from as many states folded themselves into plush white couches on a stage, firing off stories about women who had been ignored and mistreated by the sterile medical system and overprescribed risky, understudied drugs. These women, the doctors said, needed to be treated in “holistic and restorative ways” rather than as a mere collection of organs and symptoms. They deserved answers that haven’t been given to them by physicians trained to be “one-trick ponies,” and by a medical industry that has been primarily interested in studying men.

“Women deserve better,” they said, especially when those women experience painful periods or infertility or hormonal imbalances associated with polycystic ovary syndrome.

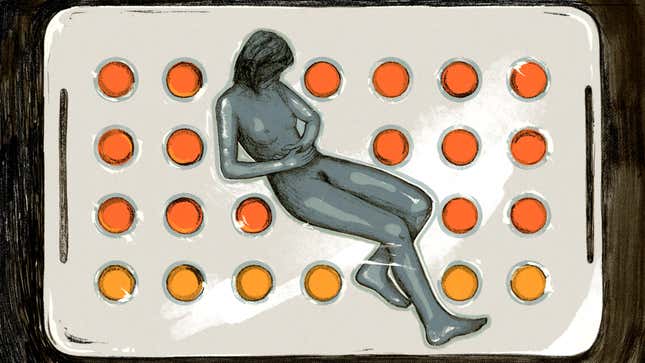

An OBGYN named Faith Daggs told the story of a teenager who went to a “traditional” gynecologist with complaints of mood swings and terrible PMS. The doctor, according to Daggs, told this impressionable girl that “we’re going to give you the panacea for all that ails women,” a medication that, in Dagg’s estimation, pummels a woman’s natural state into submission with risky chemicals in exchange for side effects like hair loss, sexually transmitted infections, and an increased risk of cancer, among more existential threats.

“And what’s that, ladies?” she asked. Eight hundred of the anti-abortion movement’s most committed activists responded in unison: “The birth control pill!”

“The birth control pill is the only medicine that is given to a healthy person who is fertile with the intention of making them sick,” Daggs explained. “We’re talking about pregnancy as a disease. We’re talking about anything that comes out of a woman—a period, a child—as a problem that we need to suppress and shut down.”

Like the other doctors onstage, Daggs is a staunch Catholic. For decades, the Catholic Church has been the most uncompromising faith when it came to the issue of employing contraceptive “barriers” as a husband and wife take to the marital bed. As Protestant leaders spent the ’70s weighting the “birth control question” and came in many cases to accept hormonal contraception as a scientific marvel supporting God’s plan for a harmonious marriage, Catholics had the Humanae Vitae of 1968 to reaffirm birth control’s inherent sin.

The Pro-Life Women’s conference, anchored by Abby Johnson, America’s most famous former Planned Parenthood employee, was in its third year when I attended last August. It was as much a celebration as a strategy session: The movement is winning the policy war. A few weeks after the event, a woman the next state over was arrested for miscarrying her child. Two months later, a group of Catholics petitioned the Supreme Court to review their case against the state of Pennsylvania, arguing that a religious nonprofit should be exempt from Obama-era rules requiring most employers to cover birth control. It triggered the judicial process that would effectively end the contraceptive mandate in July of this year.

But the women at the conference in New Orleans weren’t preoccupied with the dry politics of appeals and amicus briefs. They were armed with statistics from the liberal Guttmacher Institute and messages of radical love for potential mothers. In the halls of the Pontchartrain Center, giving birth was feminism incarnate, the most glorious calling a woman could have. With the political battles tilting in their favor, these 800 women had assembled to plan how best to dismantle the moral structures that make abortion an option.

The movement refers to this as making abortion unthinkable. Attorney Michele Sterlace-Accorsi, the executive director of Feminists Choosing Life of New York, expanded on this when she took the stage in a grey pantsuit to give the conference’s keynote, a vigorous call to action delivered in staccato bursts.

“Abortion is an attack on a woman herself! It takes the male body as normative,” she said. “It treats her like a disease.” The abortion mindset, she explained, “elevates womblessness,” and removes a woman’s inherent “feminine mystique,” including the ability to help those who suffer, to be “selfless yet self-sufficient,” and, of course, to bear children.

“Women need not resemble men!” Sterlace-Accorsi shouted to loud applause.

A few yards away, a booth advertised one of several cycle-tracking contraceptive techniques declared “we don’t let chemicals kill the chemistry.” Pamphlets promised “organic love” and “natural womanhood,” hawking five-part audio programs and ovulation workbooks. In the expansive, invigorated world of the modern anti-abortion movement, the Catholic position on the Pill has been mainstreamed and tumbled together with longstanding anxieties about feminism’s destructive effect on the family. And in recent years, those anxieties have expanded to address more universal concerns about the medical industry’s failure to accurately treat or diagnose women—a resonant message that could, as much as any legal brief or federal rule, put a dent in the roughly six million women using contraceptives in the United States.

Abby Johnson has been describing a single event since 2009, when she walked out of the Planned Parenthood where she worked and directly into the office of the Brazos Valley Coalition for Life, informing an anti-abortion advocate she could no longer stand to kill babies.

Religious activists had been trying to convert Planned Parenthood employees to the other side for decades, a tactic that seldom, if ever, worked until Johnson appeared. Within months the then-29-year-old—whose story of witnessing a baby recoiling in pain during an ultrasound-assisted abortion has been disputed in court and in the press—was on a plane to New York to begin a professional speaking tour that has seemingly continued without end since that moment. Her 2010 memoir was optioned into the movie Unplanned, which opened in 2019 and had grossed almost $19 million by the end of its theatrical run. Johnson’s ministry of former Planned Parenthood workers claims to have helped more than 400 women quit working for the “abortion industry.” And, somewhere along the way, in the early 2010s, the effusive Texan came out against “artificial” contraception entirely, eschewing hormonal contraception and condoms to use calendar-based “natural family planning” methods instead.

People think we’re nuts. You start talking about not taking birth control, that’s so countercultural, people think you’re crazy

As Johnson told a crowd at a 2018 fundraiser for Natural Womanhood, a nonprofit dedicated to promoting “natural alternatives to contraception”: “People think we’re nuts. You start talking about not taking birth control, that’s so countercultural, people think you’re crazy.” When she sat crying on the floor of the Coalition For Life offices all those years ago, Johnson recalled, she said she would never be against the Pill. But now, as she sees it, Planned Parenthood is getting women on the drug early because they know it will fail, and they can make more money on abortions when the medication doesn’t work. (“Self-control doesn’t make them any money; birth control does,” she said, an oddly anticapitalist riff on a longstanding abstinence-only adage, and a statement which is untrue.)

Surrounded by donors, Johnson listed the side-effects of the birth control pill, some more scientifically sound than others: risk of cancer, risk of stroke, osteoporosis, risk of heart attack, risk of STIs, and risk of HIV. If a woman is “that desperate to not have a baby that she’s willing to risk that harm to her body, and she does get pregnant, the next logical step would be abortion,” she said. Doctors, Johnson has written elsewhere, hand out birth control pills like candy: “They treat women like we’re too stupid to understand our bodies; as if we’re second class citizens when it comes to healthcare.”

The menacing specter of a corporation treating a woman’s body as its laboratory has crept steadily into the anti-abortion movement’s established scripts, borrowing language from the feminist health movement as well as functional health, but revamped to fit this particular anti-abortion message. Lila Rose, the 31-year-old founder of radical anti-abortion group Live Action, has similarly harped on the failures of the medical establishment: In a 2015 interview, she claimed that “self-proclaimed ‘pro-women groups’” were trying to silence the conversation about the Pill. It’s because, she said, “they are afraid of challenging the pharmaceutical status quo.” Sounding more like a spokesperson for lilac oil than for childbirth, Rose added that women were “focused on eating organic, going vegan, avoiding processed foods or certain chemicals.”

“More and more,” she continued, it seemed like women are rejecting the medical industry’s dictums to focus on “how we treat our bodies.” Birth control “isn’t healthcare,” she explained last year: “Imagine taking a drug designed to target a healthy part of your body and make it stop functioning.”

Fueling concern about medical intervention is a clever tactical move: There’s a dearth of definitive research on the dozens of brands of combination birth control pills, and it’s far easier to debunk the idea that abortions cause breast cancer, for instance, than it is to say the Pill is perfectly safe. Women report a huge number of symptoms depending on which form of pill they take. The list includes everything from nausea to a lack of mental clarity. One particularly viral study has suggested a correlation between treatment for depression and use of the pill (others refute this); some brands have been shown to lower bone density in young women. The risk of blood clotting is still real: If a woman experiences haloed migraines or smokes while taking many forms of hormonal birth control, the chances she’ll have a stroke increase exponentially. And medical device companies have marketed and sold contraceptive products—Dalkon Shield was a particularly horrific example—that have killed or injured hundreds of thousands of women. As of 2019, Bayer settled over 1,000 lawsuits related to its brand of combination pill, Yaz.

“We do our best to make things as scientifically rigorous as possible, but humans are not robots,” Dr. Zia Okocha, a family practitioner in Minnesota and a fellow with Physicians for Reproductive Health, tells Jezebel. “People can have very different reactions to the same concentration of hormones.” She says sometimes patients can go through six brands of the combination birth control pill before the seventh finally works. It’s a tight metaphor for the cynical logic that dominates women’s relationships to the medical industry: in exchange for decoupling procreation and pleasure, one might have to suffer through the discomfort of six discrete sets of side effects, unsure of if or when the alchemy will ever balance out.

Individual testimonies have filled the space left by the lack of research, hobbled by a lack of funding or will in traditionally male-dominated fields. There’s a growing secular movement around rejecting the Pill, bolstered in online forums and naturopathic practices, among people who at their most extreme appear to believe that every woman who takes hormonal contraception is mentally and physically ill. This is all in addition to the fact that the pendulum has swung wildly in the decades since the original Pill was introduced in the 1960s. Skepticism of the medical industry is high, particularly among women who are statistically most likely as a class to be misdiagnosed or overprescribed. Targeted interventions have fallen out of favor, replaced by treatments focused on preventative measures and whole-body health.

To the secular birth control skeptic, the sex-positive feminism of the ’70s mistakenly looked for salvation in the form of pharmaceuticals, alienating women from their bodies and preventing them from crucial holistic knowledge of their cycles. Enshrining “fake periods” and suppressing the symptoms of being alive and female, they say, the medical industry has conned women into lifelong dependence on a risky drug. The new woman-led anti-abortion movement has similarly become preoccupied with the Pill’s effect on the body and its stifling of women’s innate physical qualities. Sometimes, from a distance, it can seem as if the central difference between these two movements is whether you believe “natural” is the morally correct state of being for a woman, or simply a part of God’s most holistic, divine plan.

But if the Pill has become the target of anti-abortion activism, then the foundation for the movement was laid decades ago. In the ’60s, around the time

Griswold v. Connecticut legalized the baby pink Enovid pill for couples whose union had been approved by the state, mainstream religious leaders elevated marital harmony over God’s natural plan for a woman’s womb. In 1959, Billy Graham

told a group of reporters he saw “nothing in the Bible that would forbid birth control.” An influential article in

Christianity Today seven years later concluded contraceptives like the Pill could be acceptable for married couples, provided it helped them “achieve a better relationship.” The Christian Medical Society affirmed the use of contraceptives, too, provided they were deployed in “

harmony with the total revelation of God for married life,” a reflection of a broader consensus that scientific and pharmaceutical progress could be compatible with, or even enhance, a pious life.

Decades later, more conservative critics would consider this an unnecessary recompense, a bending to the looser sexual morals of the time, and an attempt by some denominations to distance themselves from the Catholic Church, which in the late ’60s, stunned many of its adherents by condemning birth control entirely as an unnatural imposition on God’s will.

A small group of contrarian theologians failed to make the Pill a cultural crusade in the decades that followed Roe v. Wade, in part because of the drug’s popularity, and in part because of how difficult it was to prove that the combination of estrogen and progesterone ended a human life. Through the ’70s and ’80s, Catholic writers published texts on the “violence of contraceptive birth control” and the unholy practice of treating fertility as a disease. But even after Jerry Falwell proclaimed in 1980 that the Bible “clearly teaches that life begins at conception” and Randy Alcorn, an influential Protestant writer, published a 210-page book arguing that the Pill occasionally caused a fertilized embryo to flush out of the womb, anti-abortion medical panels failed to find definitive evidence that this was true.

This is in large part because of how understudied the issue is (there are ethical questions about conducting research on a human embryo) and how unlikely, given how hormonal birth control is understood to work, it is that an egg could be fertilized at all. Most modern forms of the combination pill act in three ways: First, estrogen prevents ovulation, and progesterone renders the uterus inhospitable to semen. As a secondary side effect, in the extremely rare event that a woman would ovulate and additionally that sperm might live inside of her long enough to fertilize an egg, hormonal birth control could potentially render the womb inhospitable. How often this happens, and whether it happens at all, is still a subject of debate, as is whether it would qualify as an abortive phenomenon at all.

These questions were supposedly answered by a handful of anti-abortion organizations in the late 1990s and early 2000s: One group of 20 religious OBGYNs argued the “theory” of an abortifacient birth control bill came with “a significant weakening of our credibility,” given its tenuous relationship to fact. Focus on the Family, one of the most influential anti-abortion organizations in the country, didn’t consider the Pill an abortifacient through the aughts. But in 2018 it published a policy brief hedging on the issue, encouraging prayerful individual research and recommending against progestin-only pills.

The delta between Focus on the Family’s positions a decade apart can be explained in part by the development of the morning-after pill, which introduced a new enemy: An over-the-counter abortion, supposedly “on demand.” The drug reinvigorated interest in pharmaceutical interventions, sliding the moral focus from the fetal ultrasound back to the second a woman placed medication on her tongue. Complicating the issue, most emergency contraception acts in ways quite similar to the Pill, preventing ovulation, and occasionally halting the implantation of a fertilized egg as a stop-gap: If the movement was to take on emergency contraception, it would also be forced to expand its scope.

By the midpoint of George W. Bush’s presidency, conservative Christians had begun to successfully fold anti-contraceptive ideology into an administration invested in pleasing its religious base: For instance, by appointing the Mormon anti-contraception doctor Joseph B. Stanford, a man who argued a condom encouraged a husband to consider his wife an “object of sexual pleasure,” to sit on the FDA’s Reproductive Health Drugs Advisory Committee. Such political installations appealed to what Albert Mohler, a wildly influential Evangelical and the president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, described at the time as a growing number of Christians who had begun to rethink the evangelical stance on birth control, calling the “effective separation” of sex and procreation one of the most “ominous” events in recent years.

By 2006, the year the FDA approved the morning-after pill for over-the-counter use, sermons on contraceptive use were beginning to appear more frequently in churches. A smattering of Republicans also inferred publicly that hormonal contraceptives could cause abortions, among them Representative Chris Smith (co-chair of Donald Trump’s Pro-Life Coalition in 2016) and Senator Mitt Romney. As religious pharmacists filed complaints or simply refused to fill prescriptions for the morning-after pill, the Pro-Life Action League hosted a conference dedicated to exposing the “myth” that birth control was “good for society.” In a talk during the event, which the New York Times referred to as a “coming out party” for the anti-contraceptive movement, the Catholic gynecologist Janet Smith proposed that birth control introduced the idea of an “accidental pregnancy”—a false pretense—and disrupted a woman’s “natural balance of hormones,” which might hinder her ability to find a suitable mate.

Around the same time, an editor at Christianity Today used the metaphor of a romantic relationship to write about quitting the pill. (“Mircette and I became one shortly after my wedding day,” she began.) Mircette, she wrote, had been a selfish “safety lock’ not just on her womb but on her career and her gym routine, a way to prevent the “inconvenient interruption” of a “god-sent guest.” Some months later, in August of 2006, the publication ran a cover story headlined “The Case For Kids.”

While the courts debated whether a pharmacist could refuse to hand over the morning after pill, a small hardline faction against birth control coalesced, incubated in the Chrisitan homeschooling movement, and bolstered by online newsletters and forums. The major texts that inspired the Quiverfull movement may have been written in the ’80s and ’90s, but by the mid-2000s its adherents were estimated

to number in the low tens of thousands. Named for an Old Testament Psalm, Quiverfull metaphorically likened children to arrows, suggesting kids were not just a gift but soldiers in God’s army. Obedience to God started in the domestic sphere, with men as the head of the household and women the caregivers, bound by Biblical duty to procreate. For the strictest adherents, birth control, including the rhythm method, was a selfish rejection of the greater divine plan. Infertility was to be met with prayer.

As Mary Pride, who wrote in one of the movement’s foundational texts The Way Home: Beyond Feminism, Back to Reality, put it, true Christian women had to realize that “my body is not my own.” A reformed feminist, Pride believed “planned barenhood” and careerism had been unfulfilling for women, a refutation of the natural order. “Childbearing sums up all our special biological and domestic functions,” she wrote. “God intended women to spend their lives serving other people.” In her writings, and in interviews, Pride centered her ideology on the “natural” state of the body as a tribute to the Lord. (Pride initially rejected natural family planning but, in the sequel to The Way Home, noted that NFP could be used very sparingly.)

Quiverfull could have been just another Christian cult, but the media was eager to cover these unusually large families, and adherents appeared on Nightline, Good Morning America, and on Fox to explain their belief that God is the only “opener and closer of the womb.” But it was the Duggar family that was the public face of Quiverfull: The wide-eyed, Midwestern stars of 19 Kids and Counting, a show about a sprawling born-again Christian family who, along with fundamentalist practices like chastity until marriage, spurned all forms of birth control. At its peak, 19 Kids and Counting was among the highest-rated shows on television for adult women.

Quiverfull solidified in the margins—in homeschool groups and small non-denominational churches, bolstered by industrious fringe thinkers and tight alliances between families. Some of its most popular personalities also held beliefs that weren’t compatible with the daytime television circuit: Charles Provan, author of The Bible and Birth Control, denied the stories of Holocaust survivors. Nancy Campbell, who published Be Fruitful and Multiply along with a prolific Quiverfull magazine and blog, offered a literal interpretation of the arrow metaphor, hoping to outbreed a Muslim threat with her bountiful Christian heirs.

The media treated the movement as a curiosity, a series of newsy lifestyle segments only vaguely more rigorous than the long-running Duggar show. But Evangelicals with larger platforms, like Albert Mohler, the longtime birth control skeptic, saw an opportunity in Quiverfull: As he told Newsweek’s 3 million readers in 2006, “If a couple sees children as an imposition, as something to be vaccinated against, like an illness, that betrays a deeply erroneous understanding of marriage and children.”

Katheryn Joyce, who wrote a book on the Quiverfull movement, found after spending time with several families that many were drawn in through research on the birth control pill’s supposedly abortifacient elements: endless, natural childbirth being a coherent if extreme conclusion a person could draw from the idea that hormonal birth control is a form of murder, and that God fundamentally wants women to procreate. The mothers also believed, as Joyce wrote, that they were “domestic warriors in the battle against what they see as forty years of destruction wrought by women’s liberation: contraception, women’s careers, abortion, divorce, homosexuality and child abuse, in that order.”

Obscure as it was, the Quiverfull movement publicly synthesized the Catholic position on birth control with Protestant anxieties about feminism and shifting familial roles

Obscure as it was, the Quiverfull movement publicly synthesized the Catholic position on birth control with Protestant anxieties about feminism and shifting familial roles; it was also among the first visible anti-contraceptive movements centered around the testimonials, and thus the desires, of women. In 2009, Quiverfull mothers and their allies filled a stadium in Chicago, sharing the conviction that modern society was experiencing “the consequences of abandoning God’s design for men and women,” who were equally valuable, yet naturally ordered to occupy distinct roles.

A decade later, in Louisiana, I found a version of that message professionalized in a pantsuit and delivered with the jargony punch of a TED Talk when Michele Sterlace-Accorsi took the stage to announce that “true feminism embraces womanhood” in its most natural, child-producing form, swapping Biblical references for gestures to “the body politic” and “normative thought.” But by that time her position was no longer on the fringe.

Mike Huckabee, the former governor of Arkansas, made for an unlikely bellwether when he stepped up to the podium at the Conservative Political Action Conference in 2012, striding out to a song by the country husband-and-wife duo Thompson Square. The twice-overlooked presidential candidate hadn’t attended the conference since 2010; the party, he’d decided,

had become too Libertarian, straying from the culture war staples of the Christian right. It had invited a GOP gay rights group to co-sponsor the event, after all.

But when Huckabee returned that election year, it was to deliver a very specific message ahead of November: “I want to begin today by doing something that you probably didn’t think was going to happen at CPAC,” he said, fingers wagging heavenward, the mannerisms of a man who learned to be a politician by tending a Baptist flock. “I want to say a great big thank you to Obama,” he said. “Thanks to President Obama, we’re all Catholics now.”

In the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate, a fractured GOP struggling to find consensus on its long-standing family values platforms discovered a tangible enemy, not so much in contraception itself, but the idea that under a liberal regime, a religious person might be forced to provide what was considered a form of socialized medicine at the expense of their deeply held moral beliefs. From July of 2011, when the Department of Health and Human Services first published a memo imaging contraception as a basic American right, religious leaders revolted. Catholics bucked at the concept that birth control could be considered preventative healthcare, repeating the logic that “pregnancy is not a disease.” For Evangelicals, either collapsing or misapprehending the distinction between hormonal birth control became a useful rhetorical device.

In reality, the execution of the ACA’s contraceptive rules, established after several revisions in August of 2012, were calibrated to prevent just this division in response to pushback from religious organizations and the recommendations of then-Vice President Joe Biden. When the contraceptive mandate went into effect, most church-affiliated organizations could decline to provide birth control directly, signing paperwork to place the burden of payment on an insurance company rather than the exempted institution itself. But none of those compromises could combat the growing solidarity between religious entities who believed Obamacare represented an egregious encroachment on the church by the state: Rick Santorum, once considered too radical for the party given his belief that contraception’s cultural effect was “counter to how things are supposed to be,” reiterated on live television as a presidential candidate that states should have the right to ban contraception entirely in a way that had been illegal since 1965.

By the end of 2012, there were more than 40 lawsuits making their way through the courts affirming a growing GOP consensus on birth control’s relationship to religious freedom—most notably with the Hobby Lobby case, in which a for-profit corporation with Evangelical owners refused to cover IUDs. Hobby Lobby won the right to refuse care, and the Supreme Court directed lower courts to hear similar challenges. Three years later, the organization behind the March For Life, one of the country’s most visible anti-abortion advocacy groups, filed a lawsuit naming oral contraceptives a form of abortion. Abby Johnson came out against contraception. The Pro-Life Action League’s executive director rejected the idea that a women’s “capacity to become mothers is a disease that needs to be cured.” After decades of relative obscurity, the connection had been made clear enough for everyone to see.

A political lifetime but just a few calendar years later, Brett Kavanaugh described the Pill as an “abortion-inducing” drug during his Supreme Court confirmation hearing, a comment that in the wake of his petulant performance following Christine Blasey Ford’s rape allegation, barely registered. Two years after Kavanaugh’s confirmation, in July 2020, the court reversed the contraception mandate entirely at the behest of the Trump administration. Among the first clinics to be granted a few million in federal funding under the Trump Administration’s guidelines was Obria, a Christian medical center that’s rebranded from a crisis pregnancy center to a “holistic” and “comprehensive” alternative to Planned Parenthood. It is the first Title X clinic in American history that does not provide contraception to people who walk through its doors.

“We must bust open the pro-choice narrative that the pro-life movement is white men telling women what do to,” Sterlace-Accorsi told the conference crowd outside of New Orleans. And if the goal is to dismantle the “abortion mindset” and convince women to equate contraceptives with the hollowing out of a woman’s fundamental spirit there are more intimate battles to wage than the ones being orchestrated in the Supreme Court.

Today, the majority of Americans—even Catholics who regularly attend Mass—don’t consider birth control morally wrong. As of 2016, most people still believed employers’ insurance should cover contraceptives. It’s estimated that more than half of women in the United States are currently using some form of birth control, several million of them some form of the Pill. But there is a resonant language that’s been boosted among secular Pill skeptics that has proven to be a useful scaffolding on which the anti-abortion movement’s contraceptive ideology can hang: It’s the language I heard at the conference over the summer when an anti-abortion gynecologist from Philadelphia spoke of “treating a woman not as a uterus, or a pair of ovaries, but as a whole person” after being taught to “suppress” every medical issue with dangerous contraceptive drugs.

The idea that the Pill is damaging women’s bodies and minds is grounded in the absence of solid information, along with a reasonable level of suspicion and a raft of individual truths

The idea that the Pill is damaging women’s bodies and minds is grounded in the absence of solid information, along with a reasonable level of suspicion and a raft of individual truths. When Cosmopolitan set out to survey 2,000 women about their experience with the pill in 2018, it found about a quarter reported “side effects,” though they ranged from depression to weight gain and didn’t discern by brand or hormone combination. (Nearly three-quarters of those women were reported to have either stopped or considered stopping use of the pill during the prior three years for reasons that were never fully explored, though the “Goop factor” was invoked.) In researching this story, I learned that the Pill has been reported to cause a range of side effects, among other things: vitamin depletion, acne, hair loss, hair growth, low libido, mood swings, pain during sex, chronic infection, depression, UTIs, anxiety, fatigue, insomnia, infertility, light or heavy periods, headaches, “leaky gut,” inflammatory bowel disease, and autoimmune disease. But the loudest voices argue hormones are robbing women of something more spectral, what amounts to an intangible piece of their souls.

The summer I visited the Pro-Life Women’s Conference, journalist Jennifer Block published Everything Below the Waist, one of many books in recent memory to attempt to address the massive, unwieldy problem with women’s healthcare in the United States. It was named by Elle magazine one of the best books of the season. The first chapter, unsurprisingly, was on the Pill. It was critical of the “engineered bleed” brought on by taking the medication, and quoted at length a psychiatrist who said she’d steered patients away from hormonal birth control, concerned over reports of low sex drive—and a study in which women on the Pill declined to report attraction to men researchers had deemed their “best genetic match.”

“The thing I’m really worried about,” the psychiatrist told Block, “is that because [women] are on antidepressants and the Pill, they’re not capable of mating the way we’ve been mating for thousands of years.” Elsewhere, a midwife and fertility instructor tells Block that “in our intention to get our body out of the patriarchy, we’ve actually put upon ourselves the same injustice. Because we’re trying to control our bodies rather than living in harmony with nature.” This gender-essentialist critique is echoed by other prominent skeptics like Sarah Hill and Holly Grigg-Spall, who have written in their respective books that the Pill is “making women a different version of themselves” and that “every woman taking the pill will experience, over time, impaired mental and physical health.”

The Pill, once a symbol of the sexual revolution, has come to represent for many the patriarchal tendencies of the medical establishment. And as the wellness-adjacent worry it’s removing an intangible and crucial part of their womanhood, they intersect with patently Christian ideas about natural bodies and the neutering of women’s essential reproductive functions as a pressing social ill. The religious language that denounces “treating fertility as a disease” has co-mingled in secular circles, which, given the anti-abortion movement’s preoccupation with mirroring Planned Parenthood’s control of the scientific narrative, appears to be the idea. Lisa Hendrickson-Jack, a prominent Canadian blogger who teaches fertility-awareness based method of contraception wonders “why so many women are lining up to temporarily ‘cure’ themselves of their fertility.” The founder of Natural Cycles, a pro-choice cycle-tracking app, recently highlighted a glowing review praising the company for recognizing “our fertility is not a problem to be solved, but a blessing.”

The cross-pollination of rhetoric leaves women interested in ditching the Pill may find themselves sifting through duplicitous information. As a Catholic OBGYN noted on one of the occasions she was featured on Hendrickson-Jack’s “Fertility Friday” podcast, it makes sense religious providers, having so much more experience with natural contraception, would be a central resource. During the interview, the doctor spoke about the importance of sharing the science with secular women, and the threat abandoning the Pill posed to the pharmaceutical industry’s bottom line.

“I think women’s health and family planning has become so political,” the OBGYN told Hendrickson-Jack. “I wish we could remove the politics and share this information with women.” As it happens, that provider was Dr. Marguerite Duane, who spoke at the Pro-Life Women’s’ conference I attended. “Pope Paul VI predicted the #MeToo movement,” she wrote recently. “While birth control may be marketed as liberation for women the true ‘beneficiaries’ are men.”

It could be possible to see this cross-pollination as innocuous, a heartwarming moment of solidarity among women traditionally at odds if it weren’t for the vacuum of reliable information on hormonal contraception. To take a few examples from Block’s book: the author twice implies that taking hormonal birth control can significantly increase a woman’s chance of contracting HIV, a staple statistic of Abby Johnson’s when she speaks publicly on the dangers of the Pill. The claims are based on a single study of sex workers in Africa; other, more recent studies, some in the United States, have been unable to correlate those claims. Block says that the Pill causes inflammation, which may put women at a “greater risk of autoimmune diseases” like lupus, citing one study that found inflammation in obese people taking the Pill and another that put the increased risk of lupus around 1.5 percent.

She also name-checks, albeit briefly, an organization called FEMM as a resource for women looking for a “natural” alternative to fertility treatments: FEMM, as the Guardian reported, is funded by Catholic donors and shares a phone number with The World Youth Alliance, an anti-abortion group. On its website, a doctor writes that the “side effect profiles” of hormonal birth control suggest “they are causing illness and degrading health.”

At the Pro-Life Womens’ Conference, I attended a workshop about media messaging: The goal, articulated by a marketing firm from Texas, is to wrestle Planned Parenthood for control of reproductive health information and, most importantly, to win. This requires the movement to change its public image; to become a supportive environment full of well-organized advocates for women, instead of religious nuts. What if NPR went to the anti-abortion organizations for statistics on abortion? What if CNN used anti-abortion activists’ preferred terms?

Organizers handed out fact sheets and talking points and glossaries. They ran PowerPoint presentations illustrated with photographs of tattooed couples of color. Avoid hurtful rhetoric, they said, these women aren’t murderers, they’re abortion survivors. Don’t ever say they should have kept their legs closed. The message now is empowerment; it was about choice. It’s all about finding common enemies, one presenter pointed out. “We’re in the business of solving social problems, together,” she said.

After all, said the founder of the Alice Paul Group, clicking through her slides, “Abortion is the ultimate exploitation of women.” And if contraception is abortion, it’s a conspiracy to persecute women too.

A previous version of this story referred to Michele Sterlace-Accorsi as the executive director of Feminists for Life. She is the director of Feminists Choosing Life of New York.