Is She a Winter or a Summer? The Long Fashion Legacy of Color Me Beautiful

In Depth

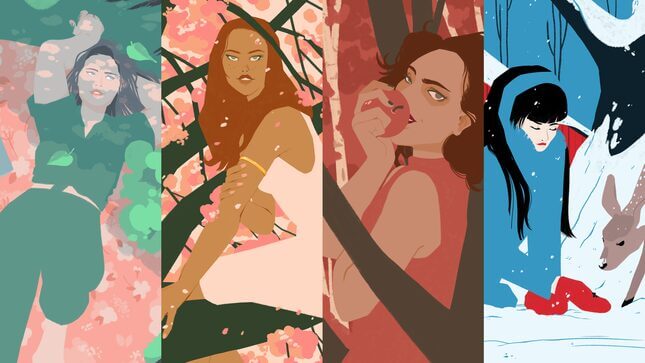

Illustration: Chelsea Beck

When Carole Jackson was a girl, she wanted “so much to be pretty,” but her reflection in the mirror—especially when she was wearing her school uniform—always let her down.

“While the powder blue uniform required at my school made some of the girls look great, it did nothing for me. It in fact made me look gray, dull, and lifeless. The color of that daily uniform robbed me of some potentially good feelings about myself well into adult life,” Jackson later wrote. It wasn’t until she finally discovered her colors, thanks to an image consultant, that she finally found “the missing link to finding [her] best self.” With the zeal of the converted, she optimized her own system, which became the style and self-help manual Color Me Beautiful.

Published in 1980, Color Me Beautiful became the foundational text of image consulting, with its mixture of how-tos and sheer conviction in color-powered magic. It sorted people (well, women first, and largely white women at that) into four big categories: Spring, Summer, Autumn, and Winter. It had nothing to do with their birthday, but instead depended on the temperature (cool—warm) and the value (light—deep) of their skin tone, hair color, and eye color. Spring was warm and light; Summer was cool and light; Autumn was warm and deep, Winter was warm and deep. You could determine it by draping yourself in different colors. The right ones would make you look healthy and, yes, younger. The wrong ones would make you look sickly and do weird things with your under-eye area and jawline. The method struck a perfect balance between esoteric and logical, and the guide remained a New York Times bestseller from 1980 to 1995, selling 13 million copies and even spawning a men’s version (1985’s Color for Men), an empire of fabric-swatch packets to carry with you while going shopping (lest you stray from your colors!), a cosmetics line, and, of course, an army of color consultants. After a lull in the late 1990s and the early 2000s, Pinterest and Instagram have revived the method, turning it into an aspirational pastime fit for the social media era—we all know, and see, how well cogent color schemes work on any feed.

But what good is knowing one’s own “Season” anyway?

“For just as nature has divided herself into four distinct seasons, Autumn, Spring, Winter, and Summer, each with its unique and harmonious colors, your genes have given you a type of coloring that is most complimented by [its own] seasonal palette,” Jackson declared in the introduction. “Color is magic and now let it work for you!” Ok then!

This proclamation, which sounds like a hybrid between astrology, medieval humor theory, and a particularly enthusiastic discussion of auras, is the foundation of one of the most timeless fashion and styling tips of the 20th century, namely Seasonal Color Analysis. It’s been 40 years since Color Me Beautiful first saw the light, quickly reaching the status of 1980s cultural sensation. But far from a curious cultural relic consigned to antique malls, the method is more popular than ever, attracting a global fanbase in the context of the color-coded aesthetics of Instagram and Pinterest and amid a reaction to fast fashion.

Seasonal Color Analysis is a palette-picking practice commodified in the 1980s, but the underlying concepts are decades older, rooted in theories developed in the 1920s by the Swiss painter and Bauhaus instructor Johannes Itten namely, that colors may be warm or cool; bright or soft; light or deep, and their combinations more or less complementary.

Around 1928, Itten began observing that, whenever he assigned his students to paint a “harmonic color combination,” each student, with their own prior knowledge of art and art history, had their own interpretation of what constituted “harmony.” That said, they tended to fall into patterns. He referred to this phenomenon as “subjective color,” which overlapped with “the area of a person.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-