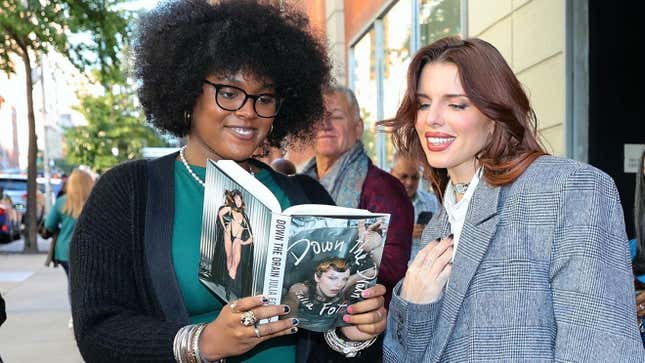

Julia Fox’s Memoir Is, In a Word, Confusing

Fox said she wrote Down the Drain without a ghostwriter and edited it herself. And wow, does it show.

BooksEntertainment

If you want to understand why Julia Fox is famous, the answer’s in her new memoir, Down the Drain, but it’s largely between the lines. She is a show-off (I mean this as a compliment) who seems to have no capacity for shame. She recalls an incident in her young adulthood, after an inebriated sexual assault, when she bought “a douche for my vagina, using it between two cars.” Sharing that in her memoir suggests that the douching in public simply was not public enough for her. Elsewhere, she grouses about “being purposely excluded from the conversation when I single-handedly started every trend of 2022.” She seems to have no self-consciousness about telling on herself; showing (with words, that is) is another, more fraught matter.

Finding one’s bearings as a reader of Fox’s prose is a challenge that lasts the entire book. I have to assume that this is somewhat by design. Drain’s style is free-flowing and chatty—I sense that she’s aspiring to classic messy-aesthetic memoirs like Jim Carroll’s The Basketball Diaries and Cat Marnell’s How To Murder Your Life. Fox is, above most things, stylish, and in the subgenre of celebrity memoirs, few entries have been this chaotic. Her lack of remorse, in aggregate, is astounding. In her book, she lies, steals, cheats, and revenge-fucks. She tells her grandfather she needs money for an abortion (that she then uses on an airline ticket). After she beats up a friend (one who we learn eventually OD’d) and is shown the facial bruises she says, “I don’t feel bad for you.” She gets thrown out of a weekend house rental and then posts on Craigslist, inviting people to “Come right in and take what you want!”

Detrimentally, Fox writes in the present tense, which leaves no time in her fast-paced dawdling for reflection. As a consequence, it’s hard to wrap your head around who Julia Fox is now. Does she stand by these decisions? Is there regret? Does she really think that slicing neighbors’ screens to let their cats out on the dangerous streets of New York City is “innocent,” or did she just think that as a child when she was doing it?

Much of Down the Drain is spent on her chaotic childhood running around New York—when she finally sees Larry Clark’s notorious 1995 flick Kids later in the book, it’s hardly a surprise that she relates. Fox, though, has a very strange idea of what’s interesting. For every potentially life-shifting event she details (like an overdose), there are more that are merely mentioned. She glosses over things like an apparent eating disorder (“We spend the next week at my mom’s apartment chain-smoking weed and binging-and-purging Nutella”) and a borderline personality disorder diagnosis (this is only revealed in a flashback to the scene in which she was briefly committed to New York-Presbyterian). Conversely, she goes very deep into incidents that, however impactful, don’t have much bearing on the story, like her friend Trisha throwing a mug at her bedridden mother, and another friend’s seemingly counterfeit suicide attempt. The book’s string of names, each of which comes with very little description, makes it hard to keep up with Fox—it’s a mostly anonymous revolving door of people that she attaches to extremely quickly and, just as quickly, stops talking about. They often say things that read like they were torn from a b-movie script: “Listen, you little brat, I’m a gangster, whether you like it or not. Maybe I overestimated you. Maybe you’re not cut out for this lifestyle.” And so does she: “It’s called spousal support! I was with you for five years! I gave you the best years of my life and if you don’t take care of me, I promise, I will make your life a living hell!”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-