Looking for Love in the Newspapers of 19th Century New York

In Depth

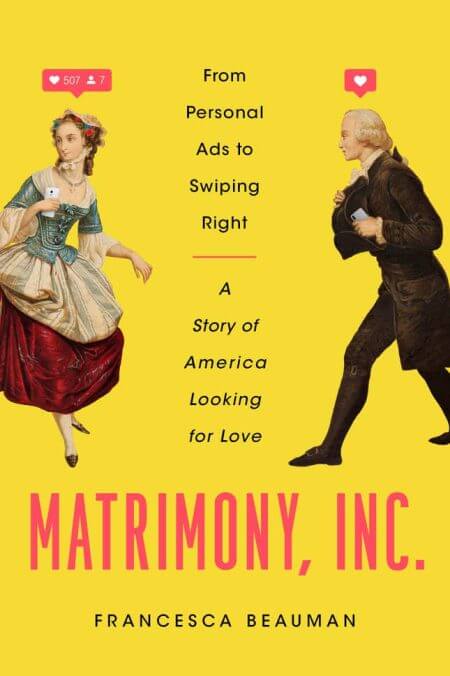

Image: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Marriage ads reached their apogee in mid–19th century New York. Prominent champions of the genre included the New York Herald and, later, the New York Times, which came to dedicate an entire column to these “parti-colored, broken and incoherent phrases of human passion,” as one journalist described them. Not only was this section of the newspaper wildly entertaining, it also offered New Yorkers a much-needed matchmaking service. Ads themselves evolved, too, demonstrating an increasingly complex and creative lexicon and beginning to reflect specifically Victorian attitudes toward love and marriage.

The continuing increase in the number of personal ads editors chose to include in their papers was in part a result of the fierce rivalry between New York’s penny presses. The New York Sun printed its first edition in 1833, followed in 1835 by the New York Herald and in 1841 by the New York Tribune. To be profitable, a penny press needed to attract readers from all sections of society. Aiming the content at both sexes, unlike the more male-orientated commercial press, was one way to do this; another was the inclusion of titillating personal ads. Take this one, which appeared in the Sun in 1840:

MATRIMONY.—The advertiser (lately arrived from the South,) being unconnected with society here, is induced to seek a matrimonial engagement through the medium of a public journal. As the advertiser is in earnest, so will he be brief in explaining his wishes—his age is 27, of a good family, moderate income, musical, fond of literature, and considered by his acquaintance of engaging manners and appearance, early habits have induced moral rectitude and religious observance. Any lady possessing accomplishments calculated to render the advertiser happy… is sought for. Money is no farther an object than as it conduces to domestic happiness. All communications will be considered strictly confidential.

The advertiser is in his mid-twenties, new in town, lacking contacts, and has sensibly decided to go public in his search for a wife. In short, he possesses many of the same attributes as other advertisers of the period not only in Philadelphia and Boston, but also across the Atlantic in London and Liverpool.

By the mid-1840s, marriage ads were a semi-regular feature of Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune, too. 1845 saw an ad from “a gentleman about 30 years of age, possessing a moderate fortune, [who] is desirous of connecting himself in matrimony with some respectable lady who is willing to undertake the charge of a small household.” In other words, he is after an unpaid housekeeper.

But it was the New York Herald (later the New York Herald Tribune) that deserved the most credit for popularizing the modern personal ad.

The Herald’s founder, James Gordon Bennett Sr., believed the role of a newspaper was “not to instruct but to startle and amuse.” Established in 1835, it made its name with sensationalist coverage of the murder of prostitute Helen Jewett. Bennett was also among the first to spot the entertainment value of ads, a significant turning point in the history of advertising.

His newspaper’s earliest marriage ad, from “Maria,” appeared on October 29, 1835, just days after American settlers in Texas, at the time governed by Mexico, fired their first shots asserting their independence.

HUSBAND WANTED.—A young lady about 21 years of age—pleasing manners and accomplished—is anxious to change her condition and would like to have a husband sometime before the 1st of January next. She has a little fortune—not much—is well connected—and has every requisite to make any gentleman of congenial habits happy in the married state. She would prefer a husband not over thirty-five—but would not refuse even forty. Fortune is not so much of an object. A letter addressed to Maria and left at the Herald office will be noticed.

A couple of weeks later, Bennett received a mysterious wedding invitation, which he eventually worked out was from the “Maria” in the ad and her speedily gained fiancé as a way of thanking him for helping facilitate their romance.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-