Paris Is Burning Director Jennie Livingston on Legacy, Controversy, and Harvey Weinstein

Entertainment

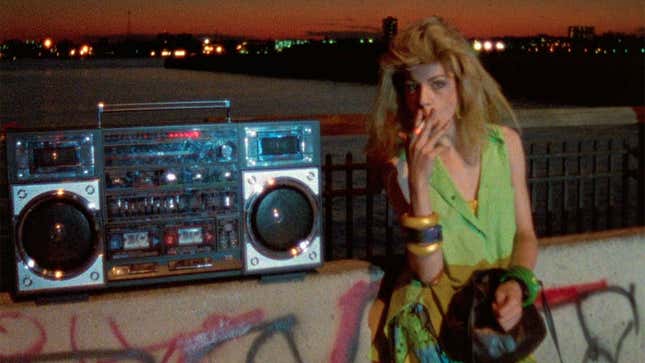

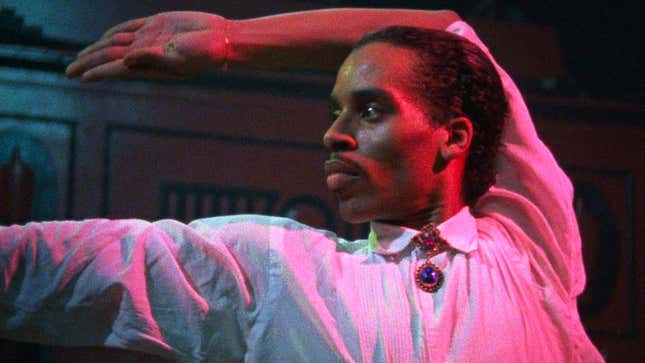

Paris Is Burning, Jennie Livingston’s 1991 documentary about the New York ball scene, has been argued over since the time of its release. The one thing I think everyone familiar with the movie can agree on is that it is enduring. As a portrait of queer POC interfacing with the harsh realities of white patriarchy, it is perpetually relevant (and made even more explicitly so via the rise of RuPaul’s Drag Race, which has overtly referenced the film and implicitly shares much of its ethos). At this point, it seems like people will be debating this movie—and the ethics of a white filmmaker capturing and commodifying a world to which she was an outsider—until the end of time.

This week, Criterion released a special edition package of the film on Blu-ray and DVD. It includes a gorgeous restoration of the movie, new conversations with Livingston and subjects Sol Pendavis and Freddie Pendavis, and perhaps most tantalizingly, almost two hours of previously unseen outtakes (the bonus footage, in fact, runs longer than the 76-minute movie itself). Last week, I met up with Livingston, who I know well enough to consider a friend, to discuss her film. (Note: Livingston identifies as genderqueer and says she’s okay with “she” and “they” pronouns. I’ve opted to use the former in this piece.) Livingston has continued working, perhaps most notably directing an episode of Pose last season, but she has yet to release her second film (she continues to work on it). Paris Is Burning remains her sole feature.

We discussed her Paris process, which began with her photographing the New York ball scene in the ’80s—she’d spend some two years immersed in it before shooting her documentary. We talked about the enduring criticisms, as epitomized by bell hooks’s searing critique “Is Paris Burning?” She told me about her dealings with Miramax, the distribution company run by Harvey Weinstein that picked up Paris Is Burning after a successful New York run, her time in the industry, and why she feels she wasn’t afforded certain opportunities to progress in her career. An edited and condensed transcript is below.

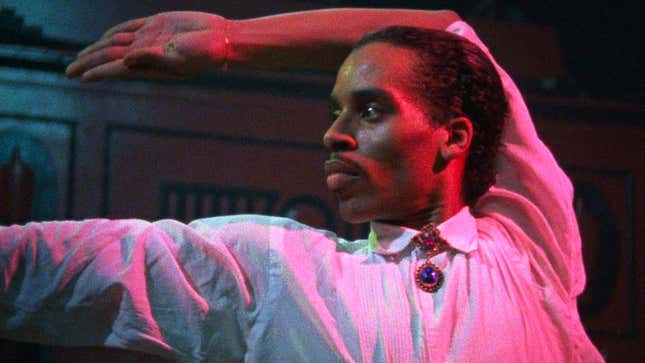

JEZEBEL: Something that really struck me this most recent time watching it is that the film positions its subjects, Pepper LaBeija and Dorian Corey, in particular, as intellectuals. I’m sure this was not at all revelatory for people in the community or even people whose identities were adjacent to it, but in terms of representation of queer people (queer people of color, especially) in film, it was radical.

JENNIE LIVINGSTON: Can you imagine how hard it was to cut that movie? I worked with a great editor, Jonathan Oppenheim, and it was a good partnership because I really loved the ideas that they embodied. I loved Dorian and Pepper because they had those brains, because I was a nerd, and it was like, “Yeah, they can look at the world and sum it up.” But obviously, I loved the dance and the spectacle and the gender transformations and gender play. In the editorial process, [we accommodated] both—you want to fall in love with these people and you want to be entertained by the performances.

I think what some people who criticize the movie often miss is that if it ever seems glib or as though it’s rushing past certain ideas, it’s all in service of entertainment, which is exactly why it still resonates.

Yeah!

If it were dry, we wouldn’t be talking about it decades later.

Exactly. And I think if, as a green filmmaker making my first film, I had had my way, we wouldn’t be talking about it because I was like, “I just want to hear Dorian talk.” No one would have sat through it. Jonathan was also a young filmmaker, a young editor. He was ripe to build something that he could collaborate with a director to make something elegant. And we did make something elegant.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-