‘Take Care Of Maya’ Shows How a Mother’s Love Can Be Used Against Her

Beata Kowalski ended her life after she was accused of Munchausen by proxy. Now, her family's story is the subject of a Netflix documentary.

EntertainmentMovies

Many likely remember the story of Gypsy Rose Blancharde, the Missouri teen whose mother, Dee Dee, inculcated within her countless afflictions she never actually had. And before her case made national headlines in 2016, Dee Dee’s own diagnosis—Munchausen by proxy—was barely discussed at all (that is, unless one read Sharp Objects, or tuned in to Season 6 of the Real Housewives of Beverly Hills).

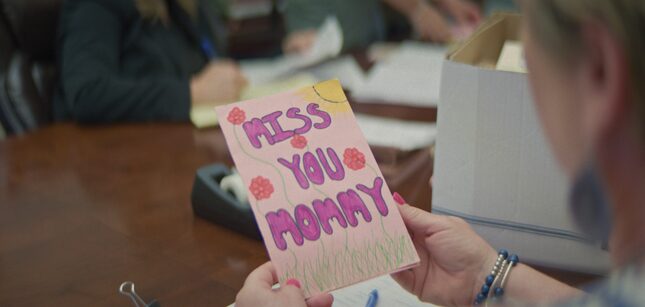

The world knows what became of the Blanchardes, but what happens when a mother is so dedicated to the care of her legitimately unwell daughter that she’s accused of the psychological disorder, legally separated from her, and driven to end her own life? Such was the tragic trajectory of Beata Kowalski, told in devastating detail in Take Care Of Maya, a documentary that premiered on Netflix on Monday.

In early 2019, the Sarasota Herald Tribune published the Kowalski family’s story for the first time. “Maya Kowalski’s only problem when she entered Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital was a severe stomachache,” it began. “By the time the preteen left the St. Petersburg facility three months later, her condition had deteriorated, her family was shattered and her mother was dead.”

Their story soon caught the eye of Take Care Of Maya’s producer, Caitlin Keating, then a People magazine reporter who later left the magazine to pursue the Kowalski family’s story full time.

“I had covered hundreds of human interest stories at People, but this one felt different,” Keating told Jezebel via email. “It felt big, complicated, and multi-layered. There was a lot of mystery.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-