The Aggressive Visibility of Camouflage

In Depth

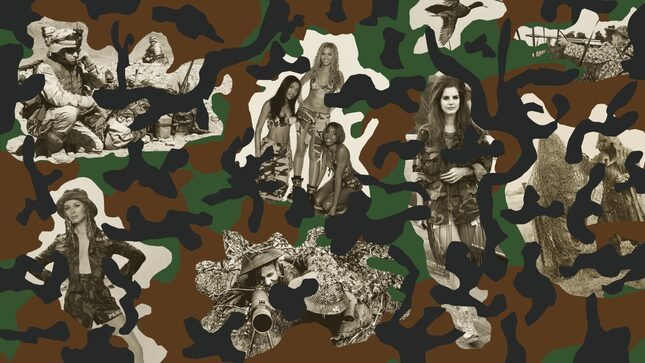

Illustration: Elena Scotti (Photos: Getty Images)

When the Trump Administration released in January the army green, camouflage-print designs for their Space Force uniforms, it took about five minutes for the dunking to begin. It was funny, I guess, to see the sixth branch of the American military stand at attention in their Air Force knockoff fatigues and talk about everything they still needed to figure out. “It’s going to be really important that we get this right,” said a representative. “A uniform, a patch, a song… There’s a lot of work going on toward that end.”

Meanwhile, Twitter comedians trotted out the jokes about outer-space jungles and Avatar. How dumb is Donald Trump, was the subtext, how dumb are these people, that they would forget the point of camouflage entirely? Camouflage is supposed to keep troops hidden against the greenery. It’s all about disguise. Don’t they know that?

That is technically true, but I don’t think the Space Force uniforms were a dumb design decision at all, that someone simply forgot about the wide, vast, dark nature of space. I think this was a canny decision, designed to make people talk. More importantly, this print was chosen to showcase power, might, force. Because camouflage isn’t about hiding. It’s about being visible.

It took humans until the 1800s to begin to latch on to the idea that there might not be some grand tailor in the sky, sewing skin suits for all animals and insects, adding a little flair here, a little tuft of feathers there. Instead, argued British naturalist Sir Edward Bagnall Poulton in his 1890 book The Colours of Animals, creatures chose their own shades through the process of sexual selection. Some birds, like the mandarin duck, likely mated their way into fabulous permanent outfits. Some snakes, like the aptly named emerald tree python, probably survived long enough to breed by blending into the vivid greens of the jungle around them. In the natural world, camouflage works to help animals sneak up on their prey undetected—or to escape from their predators—through a combination of color and pattern.

Human reliance on camouflage has a much shorter history. Up until the mid-1800s, professional soldiers mostly wore colorful uniforms, clothing that revealed their all-important allegiance to their rulers clearly and quickly—think Prussian blue or lobsterback red. As war began to change, shaped by new technologies like sharpshooting and the demands of colonial occupation, so did the outfits. Governments began outfitting their soldiers in khaki, green, and other neutral tones in the late 19th century; camouflage fabric came into widespread use in the 1920s and 1930s. For the first half of the 20th century, it made perfect sense for soldiers to wear army green fatigues. Troops were fighting wars in jungles with guns and knives and hand grenades. They used camouflage to help them be more effective predators, less enticing prey.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-