The Gouty, Flatulent, Meat-Bloated Aristocrats Who Never Stopped Eating

Latest

The term “good food” is weighted—foods that are good are healthy, nourishing, and often expensive. “Bad” foods are cheap, disposable junk. Historically, rich people have been the arbiters of which foods are good and which foods are bad, while also acting as the gatekeepers for who has access to good foods.

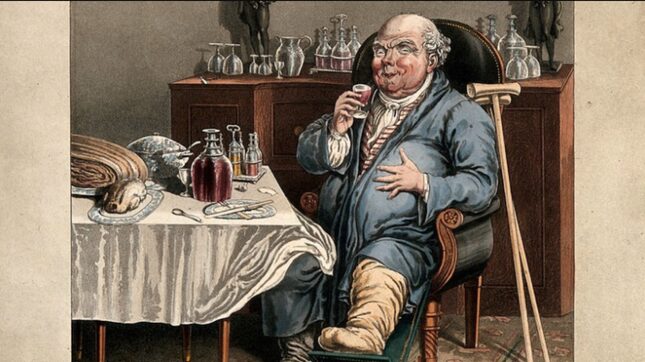

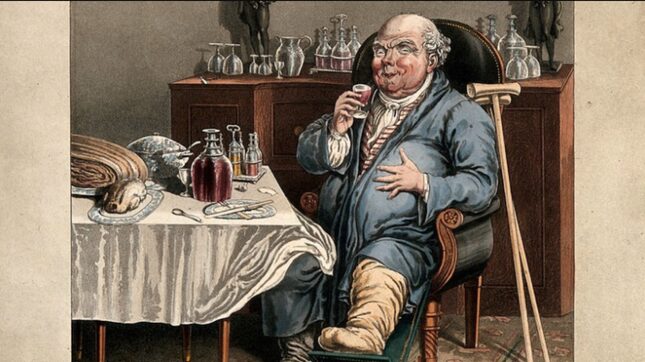

I began watching The Great British Bake Off, a wholesome show about good English cooking, because I loved Sue Perkins’s 2008 docuseries, The Supersizers Go. On Bake Off, Perkins is a punny cheerleader, rooting for contestants to succeed in recreating old-fashioned British recipes. In The Supersizers Go, she and food writer Giles Coren are less enthusiastic about historical English food. They roll their eyes through nearly every period of British culinary history, dressing and living like the aristocracy of the time as they eat mountains of bad food that rich people once considered good. When I first watched the series, seeing modern people halfheartedly attempt to mimic the pomp and circumstance of the ruling class cracking sarcastic jokes about their foppishness at every turn was a fun way to collect bits of trivia about historical weirdness. But after re-watching the series on the heels of seeing Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, a movie in which working-class people fight to the death for rich people’s scraps, it’s hard to see wealthy people’s dinner tables as anything but showcases for all the resources they’ve kept from everyone else.

The Supersizers Go began with a single, one-hour documentary called The Supersizers Go Edwardian. It was a response to the 2004 Morgan Spurlock documentary Supersize Me, in which Spurlock ate nothing but McDonald’s for an entire month. It was a joke: If Spurlock thought McDonald’s was excessive trash, he should take a look at the Edwardian Era, when the English elite showed off their wealth through all-day feasts of the richest foods imaginable, throwing away what they couldn’t eat despite the fact that at the time, 23 percent of those living in urban working households could not afford basic necessities like food. Hosts Perkins and Coren are guided through their week of Edwardian eating by cookbooks and historians, dressing the part and keeping track of the havoc the excesses of the era, with diets heavy in meat and light on vegetables, would wreak on their bodies.

The one-off documentary eventually became a two-season, 12-part series in which the pair ate according to the standards different periods in British history, from WWII rationing in the first episode all the way back to the early-modern Elizabethan period. The series originally aired on the BBC, and when I first watched in 2014, it was included on Hulu. These days, Supersizers only exists for Americans as grainy YouTube videos. But for viewers who can put up with the poor video quality, watching the episodes chronologically according to time period is an engrossing look at the ways English tastes were shaped by the exorbitant amounts of wealth amassed by colonization and privatizing land while hiking up food taxes. In the Elizabethan Era, the earliest time period covered by the series’s first season, English aristocrats who had yet to be introduced to the fork were still amateurishly dumping New World spices haphazard into pots of boiling animal entrails. But by the Edwardian era, their meals were an elaborate, never-ending banquet of complicated, intricately-prepared dishes that had about as much to do with nourishment as a mink coat has to do with staying warm.

“You know the stories of women who just wouldn’t come down for breakfast or lunch because they lived almost in fear of the tyranny of what awaited”

For example, in Edwardian England, an upper-class couple sat down to a breakfast spread of porridge, sardines on toast, curried eggs, grilled cutlets, coffee, hot chocolate, bread and butter with honey. For one o’clock lunch, their private chef would have served sauteed kidneys, mashed potatoes, macaroni au gratin, and boiled pork tongue. Afternoon tea meant coconut rocks, fruit cake, Madeira cake, toast with butter, and hot potato scones. For dinner, the wealthy could expect oyster patties, sirloin steak, braised celery, roast goose, potato scallops, and vanilla soufflé. Watching Perkins and Coren try to shovel all these meals into their bodies along with endless glasses of claret is akin to watching a goose be tube-fed for foie gras.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-