‘Pretty Baby: Brooke Shields’ Reckons With the Notion of Child as Sex Object

The model-actor, who was sexualized from a young age, revealed she was raped as an adult in the Sundance documentary.

EntertainmentMovies

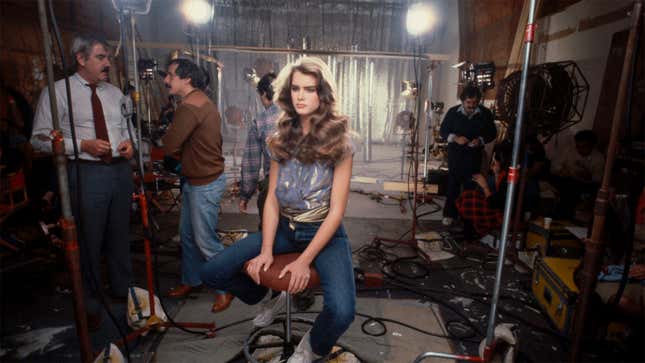

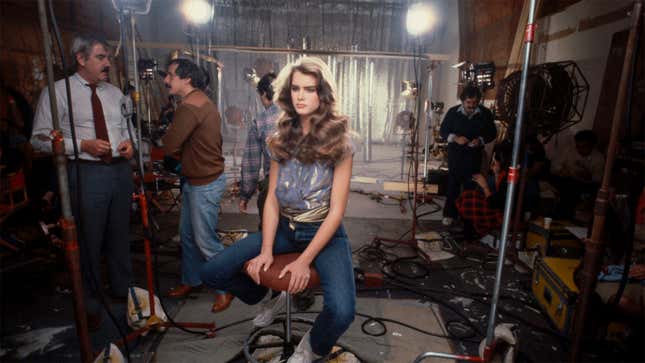

“You couldn’t make Pretty Baby now,” Brooke Shields concedes in Hulu’s upcoming two-part documentary on her life, which premiered Friday at the Sundance Film Festival. “Or a Blue Lagoon. Or Endless Love.” Even before the string of movie roles that sexualized a young Shields, her modeling was pushing in that direction. In addition to 1980’s Blue Lagoon and 1981’s Endless Love, the notorious 1980 ads Shields shot for Calvin Klein jeans further commodified her supposed sexuality: “Do you know what comes between me and my Calvins? Nothing.”

One could make the case that Shields’ early career, as shepherded by her momager Teri Shields, was built on the notion of child as a sex object—and in a certain way, that is the case that the Lana Wilson-directed documentary does make, albeit with a good deal of compassion and context. But it is the 1978 film Pretty Baby by Louis Malle that remains the most notorious project in her body of work. To Shields’ quoted point, it’s astonishing that it got made, as it portrays the 12-year-old daughter of a sex worker in a New Orleans brothel whose virginity is auctioned off. As chronicled in the doc, Pretty Baby: Brooke Shields, the movie was extremely controversial, even by the wild-west standards of ‘70s cinema, not only for its plot but for Shields’ nudity (she was 11 when she filmed it).

“America’s Newest Sexy Kid Star,” read one headline announcing Shields’ casting. “World’s youngest sex symbol?” read another. From the cover of People: “Pretty Baby – Brooke Shields, 12, stirs a furor over child porn in films.” In an interview for the film’s release that’s featured in the doc, a preteen Shields said: “I knew it was going to be done in good taste…and it wasn’t any porno movie so I didn’t feel so bad about it.” Today, at age 57, she has maintained much of this attitude. She says she “knew” the movie was “a real artistic endeavor.” She speaks about filming in practical terms: “I wanted to make everyone happy with the job that I was doing. When it came to acting, no one helped me. I was there to say these lines, to do it without any education about how to do it. That’s what Louis wanted.”

She doesn’t offer much new insight on the making of Pretty Baby, either. She wrote about it pretty extensively and unapologetically in her 2014 memoir There Was a Little Girl, and she’s previously shared the story of her onscreen kiss with Keith Carradine, 29 at the time, which was her first ever. She scrunched up her face and received admonishment from Malle, but was able to perform it after Carradine took her aside and told her, “This doesn’t count. It’s pretend. This is all make believe.” In the doc, she does reveal that dissociation, like that which Carradine suggested, helped her do her job: “I think I learned to compartmentalize at such an early age, and it was a survival technique: That’s not my life. That’s not who I am.” But where Shields is today isn’t that far off from the tone of dismissal—a certain nonchalance—that she adopted in a 1981 interview with Phil Donahue: “I did it just as another job and I didn’t take it seriously, like I was going to grow up to become a prostitute or anything.” Maybe she’s just pragmatic.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-