Building a Memory Palace of Penises: The Collection Is Part Literary Experiment, Part Feminist Revenge Plot

In Depth

Jeanne is a collector of penises. She systematically feigns dizzy spells on busy Parisian streets, which invariably bring to her side a concerned man, whom she then invites back to a hotel room. There, she has sex with him, but the sex is somewhat beside the point. The point is the penis, which she observes with a matter-of-fact eye. Some penises sit at a “perpendicular angle as though the testicles—skin pulled taut, ready to tear—acted as counterweights.” Others are “semi-erect, drawing towards repose.” One is “very long, perfectly tubular,” while another has “a multitude of beauty spots.”

Jeanne takes great care to remember each and every one of them, constructing a “memory palace,” an imagined physical space through which she can mentally walk, like a museum. In each room of the memory palace lives a disembodied dick. In each case, the man to whom it belongs is long forgotten, if ever even meaningfully observed in the first place.

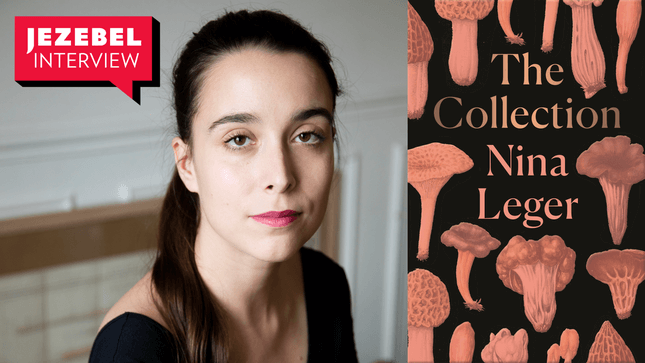

This is the electrifyingly bizarre setup of Nina Leger’s The Collection, a novella that follows protagonist Jeanne as she populates her memory palace, building “corridors, annexes and outbuildings” to mentally house the memories of all the penises she encounters. It is a literal, and yet fantastical, exploration of the female gaze: Jeanne’s dick-collecting journey begins one day when she sets her eyes upon a man’s fly on the metro and her subject is “petrified by her gaze” as she “seems to draw down the teeth of the zip one by one.” Soon after, she is so overwhelmed by the sudden realization that she uncontrollably “stared at a man’s crotch for four stations” that she nearly faints, a man comes to her aid, and, well, there she finds her routine.

The book—part conceptual literary exercise, part feminist revenge plot—was first released a year ago in French, and was recently translated and published in English. Upon its earlier release in France, it courted plenty of praise, winning the Anaïs Nin Prize, but also notably unsettled some vocal male critics. The writer Yann Moix—who once infamously announced as a 50-year-old man that he preferred the “extraordinary” bodies of 20-year-olds to those of women his same age—went head-to-head with Leger on a popular TV show to lambast the book as “old-fashioned” and “catastrophic.” These men were not only disinterested in this exploration of the female gaze, but also seemingly outraged by it.

She reduces men to their penises and places the remembered members within its rooms like pedestaled artifacts.

It’s true that Jeanne’s memory palace is, quite literally, objectifying: She reduces men to their penises and places the remembered members within its rooms like pedestaled artifacts. During her encounters, she narrows her vision to the dick, ignoring or else willfully forgetting these men’s voices and personalities, and even the body beyond the genitals. Her myopia is such that she finds herself realizing after a sexual encounter with an unremembered man that she had met his penis before; it already had its own room in the memory palace. It dawns on her that she could encounter the same man yet again and not know him until she saw his dick, because it’s still, even after this second encounter, all that she remembers of him.

Despite this seeming ruthlessness, though, Jeanne takes great care in sensually exploring and detailing and remembering each and every penis, without any judgment. “She accumulates, but looks for nothing; she is not searching for a penis that would surpass all others and give meaning to her explorations, imposing their limit,” writes Leger. “She collects without comparison, adds without judgment, showing neither preference nor disdain.” She seems to have an appreciation of all of them, no matter size or quirks in coloration or shape. All penises are equal and belong in the memory palace, whose layout is intentionally constructed without any kind of hierarchy.

The occupants of the memory palace are described in luxuriating detail, but we never see anything of Jeanne—her hair color, age, marital status, or profession. Nor do we learn what Leger dubs the “whys” and “becauses” of Jeanne’s behavior; there is no knowing what motivates her. As Leger tells it, she wanted to withhold these details to challenge the impulse to pathologize women’s sexuality. Of course, any person who steps outside the bounds of heterosexual, marital, procreative sexual behavior can become a target of critique and diagnosis. But the popular vision of the essential nature of straight men’s desire is something akin to a mental encyclopedia of boobs. An obsessive and objectifying relationship to sex is seen as normative; a man making notches on his bedpost is considered unremarkable. The inverse, however, is treated as fundamentally suspect.

To protect Jeanne from judgment, Leger felt she had to conceal most aspects of her protagonist—from readers, and even from herself as the author. In this way, The Collection drives home the limitations of the female gaze both within the current culture and as a straightforward inverse of the male gaze. In order to effectively entertain this literary experiment, Jeanne had to be reduced to her actions and sight. This might prevent her from becoming an object and secure her as a subject, but Jeanne’s interiority is largely scrubbed blank. In her emphatic looking, her own body is rendered invisible, and so is any of her pleasure beyond the experience of seeing and remembering. She is ruthless in her mental cataloguing of disembodied penises, but not, as far as the reader is allowed to see, in her pursuit of, say, orgasm. Her encounters are highly controlled and systematic, as opposed to spontaneous, wild, or free.

But The Collection isn’t a manifesto of women’s sexual liberation, it’s a surrealistic literary exploration, and maybe a bit of a Rorschach test for readers. Jezebel spoke with Leger, whose first language is French, about confrontations with male critics and the art of painting literary peen.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-