Buy These Pajamas & Rescue a Prostitute; Or, Why Rescue Brands Are Dumb

Latest

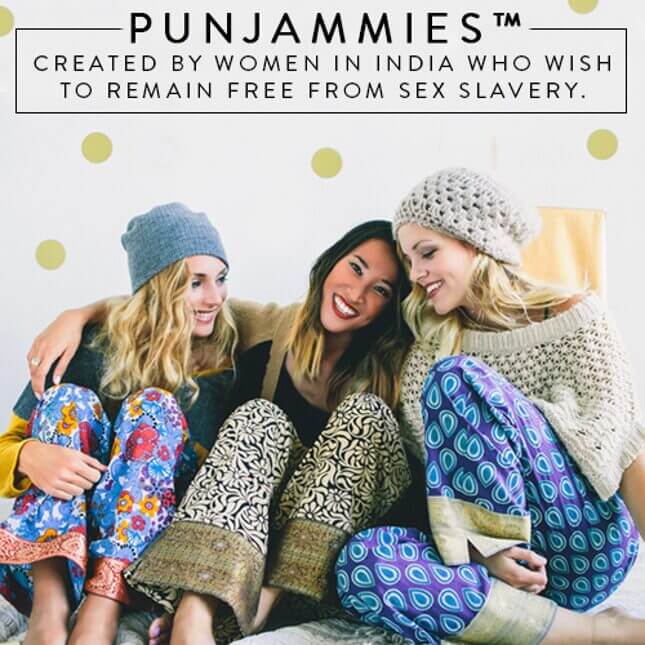

There are a great number of awful things on Facebook, so I wonder if you’ve managed to see the most awful thing? It is an ad. It shows a beautiful young Asian woman bookended by beautiful white, blonde women, and they are all cozy together on a couch, each in her own unique pair of Punjammies. The copy reads: Created by women from India who wish to remain free of sex slavery.

When I first saw the ad I felt a bit guilty zeroing in on any single horrifying element while the rest of them were allowed to innocently lurk about. Still, I had to start somewhere, and the name–Punjammies–seemed as logical a place as any. I said it aloud to myself once. “Punjammies.” My next thought was: “What flaxen-haired garden-trowel-wielding Connecticut-dwelling wife of the president of the International Bank of Satan thought it would be clever to combine the words ‘Punjab’ and ‘Pajamas’?”

Indignation, of course, is not the same as proof. I emailed the company. “I just saw your pajama pants on Facebook and they’re really nice,” I wrote. (They are.) “I just wanted to know how came up with your name? Just wondering!” I figured that if the recipient was moved to wonder if I was really a customer or just some asshole who’d read ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’, the exclamation point would throw them off the scent.

I was amazed when I received a quick answer:

“Our founder and CEO Shannon Keith was inspired by the beautiful colors of sari’s [sic] while in India and it was there that she decided she needed a practical way/skill that women would learn in order to save them from a life of sexual slavery. Pajama pants have simple lines that were easy for the women to learn which was also ideal! Punjabi [sic] is a region in India as well as a type of clothing worn so we thought combining our two cultures into one name would be perfect! J”

Do I feel bad printing this email here? A little. But as soon as any feelings of shame start creeping up, I remind myself I’m not a white woman who went with a Christian charity/Christian Mission to India in 2005 and was so horrified by human trafficking that I decided to start a company called Punjammies, a word I created by combining the name of an article of clothing and the name of a region unrelated to this particular endeavor and over 1,200 miles from where those articles of clothing are made, and then, miraculously, the feelings of shame go away.

Moving onto the image: it bothers me that the Asian woman’s attention is focused outward, while the white women look very helpful and nurturing towards her—suspiciously so, for an image with two white women around a woman of color right underneath the line “Created by women in India who wish to remain free from sex slavery.” If this were a cartoon, the Asian woman might be saying, “I just love Punjammies” and the white chicks would just be cooing something like, “We’re so glad we could make the magic of Punjammies possible! But if you want one of these stupid hats, honey, you’re going to have to bring your own. ”

The actual ad copy is “Created by women in India who wish to remain free of sex slavery.” I wonder if were there other contenders for the spot of the word “wish”? “Wish” is nuts—so breezily hopeful, as if it said “prefer to remain free of sex slavery,” or “yearn to remain free of sex slavery” or even “think it would rule to remain free of sex slavery.” The tagline is so disturbingly arch I don’t think anything I’ve imagined is much worse than what is.

Getting further inside the world of Punjammies—to their umbrella organization called International Princess Project—did not increase my sympathy. Their homepage alerted me to the fact that every Wednesday in January was Red Light Wednesday: “…Whenever you are commuting, we pause to think/pray for the people still trapped in red light districts all over the world.” I wondered if anyone with any kind of sway questioned this campaign. If they had, they might have said something like, “You all know red traffic lights aren’t the same as red lights in red light districts?” And I wonder if that concern was summarily dismissed with someone saying something like, “Hey, if there’s a social media campaign where people take selfies when they’ve just woken up as a way of raising awareness about ‘waking up’ to the violence in Syria, you better fucking believe we don’t need to give a shit if red traffic lights have nothing to do with red light districts.”

Punjammies is just one of many companies selling goods made by former sex slaves. There’s also the Nomi Network—their tagline is “Buy Her Bag Not Her Body,” a deployment of rhetoric implying she’s going to have to sell one or the other, and she is dependent on your choice to seal her fate. There’s Purpose Jewelry, “handcrafted by survivors of modern day slavery… each jewelry tag is hand-signed by the girl who created it.” There’s JC Denim, “handcrafted by girls who have been rescued out of sex slavery.” One more—just for the pun—a soap brand, Trades of Hope made by women who “have made a clean break from their previous lifestyle in the sex trade and have chosen soap-making as an alternative source of income.” The first image you see when you go to their website is a blonde white woman standing by a boat on a tropical beach wearing a white maxi dress, under the copy “Empowering Women out of Poverty.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-