Dying Mall Documentary Jasper Mall Recites an Elegy for Capitalism

The very purpose of these megastructures, one-stop efficiency, has long been trumped by online shopping.

EntertainmentMovies

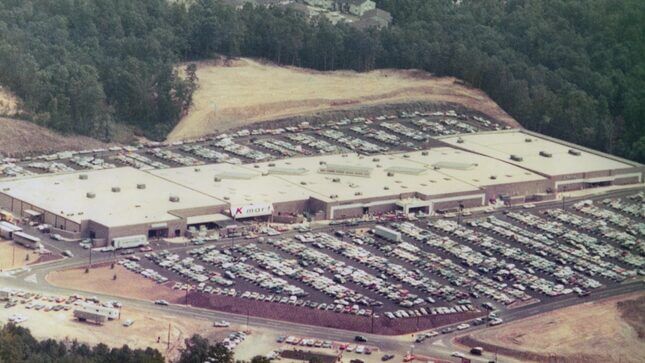

A walk through a once-thriving, now visibly depressed mall can provoke a specific kind of ambivalence. Like most figurative trips through time, it can be funny to revisit what once attracted people (or intended to) vis a vis contemporary sensibilities. The very purpose of these megastructures, one-stop efficiency, has long been trumped by online shopping. But a trek through a dying mall is sad, too. The struggling or shuttered stores, as well as the shopping center as a whole, represent unrealized dreams of entrepreneurs—dreams whose materialism and greed were not necessarily evil, but natural products of a system that forges the inequity that mars our culture. And then, because it seems overly sentimental to cry over bleeding capitalism, a third feeling prevails: weirdness over the entire experience, over feeling anything at all for a mall. Just moving through dilapidated space can conjure a psychodrama in 3-D.

Directors Bradford Thomason and Brett Whitcomb nail this bundle of strange feelings in their documentary Jasper Mall, a meditative, sensitive, and bemused portrait of a dying mall in Alabama that was filmed in 2018. Jasper Mall made its streaming debut on Amazon Prime earlier this year, and I can’t believe it’s not more of a thing, I can’t believe more people aren’t talking about it. I can’t think of better viewing in the typically slowly lived week between Christmas and New Year’s. Get on it.

Thomason and Whitcomb’s approach is reminiscent of the documentaries of Frederick Wiseman in that they’re interested in sharing their observations of an institution, not forcing a narrative. A series of interactions and testimonials—from the likes of a hairdresser at MasterCuts, a jeweler at The Jewelry Doctor, a woman named Robin whose flower shop (named Robin’s Nest, naturally) is closing—provide X-rays of decay without drilling the particular downward trajectory into your skull. The lack of specificity here—the financial particulars that led to the previously popular mall’s undoing, or even so much as an explicitly stated location—give the subject at hand a kind of everymall appeal. I’ve seen a lot of what’s documented in this movie a thousand miles away.

The movie’s de facto protagonist is Mike, who does “housekeeping, maintenance, and security.” He effectively manages the mall, desperately trying to attract traffic to a dead end. His effort is so tragic it’s as though he’s spit-shining a sinking ship (he begs someone to help him get new food vendors in there because the remaining Jasper Mall employees still need a place to eat). His motivation is deliciously opaque. Is he effectively fighting for his life by trying to preserve his job? Does he need something to believe in? Does it have to do with his former life as a Joe Exotic-type small-scale zookeeper, whose dreams, he vaguely explains, were dashed by activists? When he looks at the emptying stores that once supported a bustling shopping center, is he reminded of the empty cages that once held his “babies?” That seems to be the suggestion, but Thomason and Whitcomb are more interested in the complexities of even the most seemingly banal aspects of their story than they are in neat, succinct explanation.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-