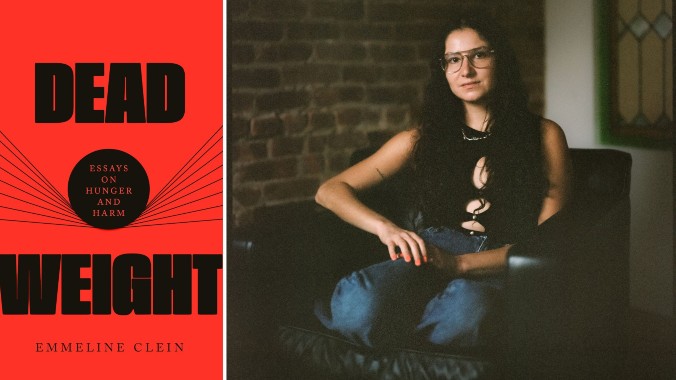

Emmeline Clein’s Reframing of Eating Disorder Culture Makes ‘Dead Weight’ a Must-Read

“Why are we only angry at the women who are in pain? Why are we not asking who taught them these coping mechanisms?” the author said to Jezebel in a recent interview.

BooksEntertainment

There are certain types of books we often find ourselves saying we ought to read: the novels long-listed for prestigious awards; the essay collections by writers whose off-beat observations go viral; the 400-page in-depth investigations about the secretive entities harming society.

Dead Weight is not a book like that. Dead Weight is a book you must read. Even if you are one of the lucky few who has never suffered from the paralyzing pervasive pressure of Western beauty standards, Emmeline Clein’s new book—subtitled Essays on Hunger and Harm—speaks to so much more. It is, in its broadest sense, a hopeful book offering an alternative, communitarian way of existing in our bodies and in the world. More specifically, it seeks to reframe the way we talk about, think about, and treat eating disorders.

Getting to this better place requires unearthing and closely examining what underpins the structures that trap us in cycles of self-hatred and self-improvement (hint: It’s often capitalism). Clein does this with the encyclopedic citations and references of a researcher, combined with the lyricism of an MFA grad (both of which she is). In another writer’s hands, the argument she makes throughout the book’s 12 essays could risk verging into the dour, sober, or pollyanna-ish, but Clein’s writing is innovative and refreshingly enervating, taking on everything from why eating disorder treatment is so ineffective (“The places meant to help patients realize that their weight is not the defining facet of their personhood are entirely oriented around their weight”) to a defense of the often-demonized eating disorder chatrooms where young women encounter their sisters in arms (who told Clein “about the isolation that accompanies a disease whose sufferers are villainized, isolation alleviated by the ‘hours [they] spent talking to people who understand’”).

In her prologue, which Clein writes primarily addressing those like her (women and girls and femmes with a history of disordered eating), she includes a line that operates as a bit of a thesis statement for the book: “I’m trying to find out what might happen if we blame someone other than each other and ourselves for a change.”

I asked her about that idea—and the series of other arguments she explores in Dead Weight—in a recent conversation.

JEZEBEL: The throughline of this book is basically that eating disorders are a systemic issue that we blame on individuals. I’m wondering how you came to that point; when did this way of thinking appear to you as the thing that might actually help people with eating disorders?

EMMELINE CLEIN: I relapsed from my eating disorder after that traditional treatment many times and I sort of ended up in a place that was like that. I think a lot of people get to sort of “recovered enough” that people aren’t worried about you when they see you, but the thoughts are still there at a very high volume pretty much all the time. And then I had a pretty bad relapse when I was working in fashion soon after college, which culminated in my experience with a Wellbutrin seizure (which you can read about in the book). But after that was when I really started kind of reorienting my whole life and being like, I need to address this. For me, it was having really open and honest conversations with other women who have been through this and doing a lot of this education. I started looking for books and texts that would offer me the context and the historicization that I actually wanted, but they were very difficult to find.

Any mental illness that does not primarily afflict women is understood as a structural issue—as well as something that individuals need to deal with—and is understood as something that is a microcosm of a lot of political and economic and social forces as well as a medical disease. Yet eating disorders get the like, “teen girls are being crazy and making each other sick online” treatment. Addiction and depression get the “addiction is late capitalism and depression is neoliberalism” treatment that does relieve blame from sufferers and understands people as pawns to these capitalistic forces. And eating disorders are, in fact, better microcosms for a lot of those forces, more nuanced ones than these other diseases.

Why are we only angry at the women who are in pain? Why are we not asking who taught them these coping mechanisms? So I wanted to give the sufferers who have been so mocked and reduced and told they were crazy a solidarity-forward kind of polemical narrative that is also taking them seriously. Let’s really map out this room you’ve been locked into and figure out who has the key.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-