Screenshot: Array

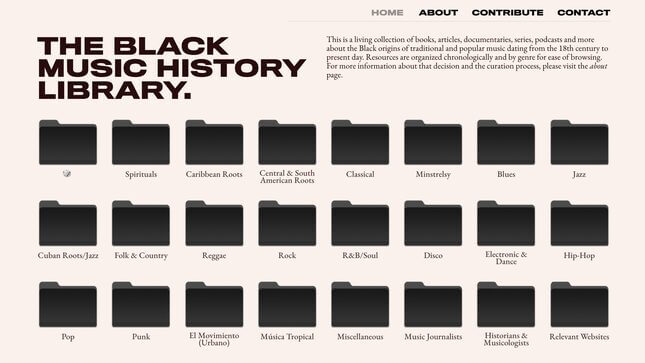

In June, 22-year-old music journalist Jenzia Burgos posted a slideshow on Instagram and wrote, “If you don’t know the history of Black artists behind your favorite music, you don’t really know your favorite music.” The post, which included reading recommendations about music’s Black pioneers in genres like country and electronic music, quickly went viral. The post’s virality inspired Burgos to build the new website Black Music History Library, which collects articles, books, podcasts, and films to outline the Black roots of different popular music genres. Simple and accessible, the still-growing collection of resources felt like something that should have always existed, especially as the music industry has faltered when it comes to interrogating how it segregates Black artists by genre.

Jezebel spoke with Burgos about creating the library, popular misconceptions of “Black music,” and the power of reading lists. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

I was thinking, What can I share that hopefully becomes a tool for somebody to use every day?

JEZEBEL: What made you start this project?

JENZIA BURGOS: In June, I shared a post on Instagram [with] the tagline: “Your favorite music exists because of Black people.” In it, I shared a few slides of books and relevant articles for some genres [because] I thought that sometimes people aren’t aware of the Black history tied to those genres; punk, reggaeton, hip-hop, which I thought was obvious, but unfortunately I see too many people whose idea of hip-hop might only be Eminem or Machine Gun Kelly. [Laughs]

The post was a response at the time to seeing lots of social media activism in light of what I like to think of as a spike in terms of an upset around racism in this country. I don’t really love the word “movement.” For people who are constantly living under a racialized state if you’re Black, if you’re brown, the idea of a movement around awareness for racism is interesting because it’s not a movement in your life, it’s something that you just have to deal with every single day. Seeing the intense mobilization of everybody on social media suddenly interested in ways to be aware of this was exciting, but also a bit limiting because I saw a lot of the same posts about how to contact your local Congresspeople, how to approach protests responsibly.

Those were all really important things to know, but at the end of the day I was thinking, What can I share that hopefully becomes a tool for somebody to use every day? I’m not an activist; I’m not an organizer. But I am a music journalist, and I love music. Music is something that’s a part of my life every day and a part of many people’s lives every day. If you’re a music journalist or working in the music industry in any capacity as an artist or on the business side, how can we make that work informed in a way that’s also anti-racist, in a way that’s also honoring Black people and Black life on a daily basis? For me, it’s [about] knowing where this music comes from.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-