New York Times Releases a Bombshell Report on the Proliferation of Child Sexual Abuse Imagery Online

Latest

On Sunday, the New York Times published a ruin-your-day (slash week slash year slash life), can’t-unsee report on the proliferation of child sexual abuse imagery online (the material is frequently referred to as “child pornography,” but the article states that “experts prefer terms like child sexual abuse imagery or child exploitation material to underscore the seriousness of the crimes and to avoid conflating it with adult pornography, which is legal for people over 18″). It is as harrowing as it is crucial, at times nearly impossible to read and yet urgently important.

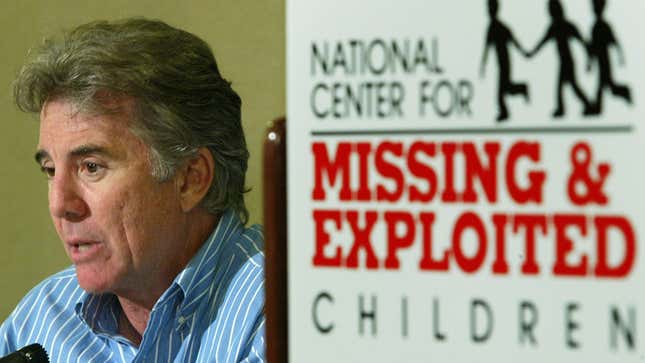

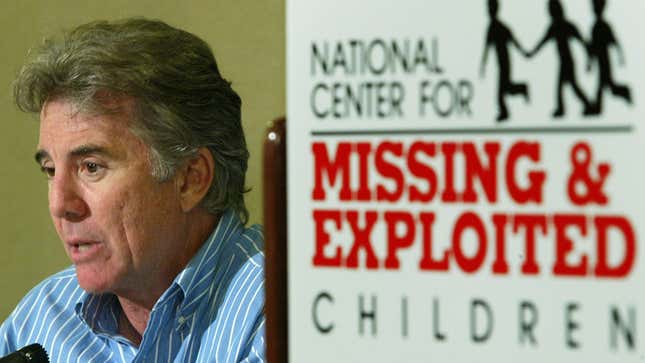

Journalists Michael H. Keller and Gabriel J.X. Dance comb through failures on several fronts—that of tech companies, the Justice Department, the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children—to help answer the question in their story’s headline: “The Internet Is Overrun With Images of Child Sexual Abuse. What Went Wrong?” It includes several descriptions of confiscated imagery of children being abused and tortured. Grueling as these are, they represent a drop in the bucket: The article says that last year, “technology companies reported a record 45 million online photos and videos of the abuse last year.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-