Paris Hilton Isn’t Dumb—She Knows How to Write What Her Fans Want to Read

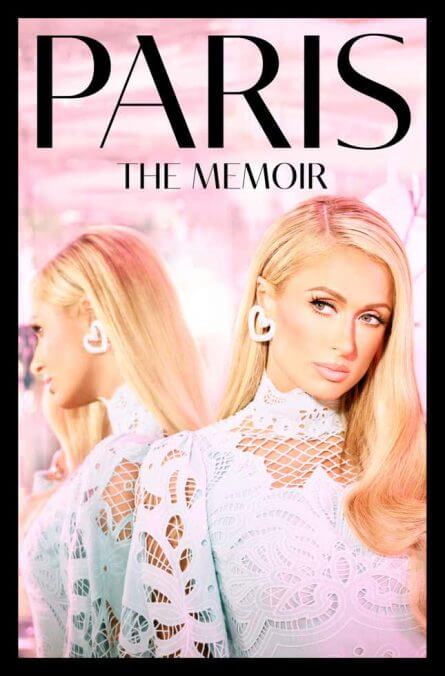

Paris: A Memoir is an abysmal mix of telling and not showing, bad sentences, and open image cultivation from a self-proclaimed "performance artist."

BooksEntertainment

Paris Hilton is an animal—or at least, that is often how she views herself retrospectively in her new book, Paris: The Memoir. Hungover the morning after her 21st birthday and en route to skydiving, she “trembled like a little wet dog.” She gets quiet when she’s scared, “like a little rabbit going purely on instinct.” She meeps “like a baby bird,” has the attention span of a gnat, and her signature walk is deemed a “unicorn trot.” In footage shot at the Christmas she spent at Provo Canyon, the “emotional growth” boarding school where she says she was sexually abused, she looks “like a goldfish out of its bowl: beaten down, emaciated, and shy, with dishwater brown hair and a forced fake smile.”

Hilton’s affinity for four-legged friendships—her menagerie has included dogs, cats, rabbits, bird, snakes, chinchillas, gerbils, a baby goat, and “even a little monkey”—is well-documented and continues to be one of Hilton’s most endearing traits, partly because of how telling kindness to animals can be (Gandhi’s “the greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated,” and all that), but also because it seems pure. The often open obfuscation that has defined Hilton’s ever-shifting public image is nowhere to be found in her love of animals.

Identity and its elasticity are key themes in Paris (out now). The book begins with a discussion of ADHD, which Hilton refers to as her superpower. “I wish the A stood for ass-kicking. I wish the Ds stood for dope and drive. I wish the H suggested hell yes,” she writes. Her discussion of her diagnosis—which occurred in her 20s but wasn’t taken seriously by her until later—works, at least initially, as a framing device. “I’m probably going to jump around a lot while I tell the story,” she writes. This includes jumping out of the story about jumping out of an airplane to discuss attending a party with Pia Zadora when Hilton was a child, and going on a tangent about the show Euphoria after mentioning euphoria (the condition). Hilton’s ADHD discussion allows her to be voicey (“Intrusive thoughts are my nemesis”) and performative—at one point after getting off topic, she asks for effect, “Wait. Where was I?”

Hilton’s performance is conscious and telegraphed. She is, by her own estimation, a “spin-sorceress” and a “people pleaser” with a “pathological fear of embarrassment.” Recounting her time in the public eye, which began in her teens as a New York party girl/Page Six staple, she admits making decisions that prioritized the safety of her brand. This is why she didn’t speak up and share her experiences at Provo Canyon and the similarly oppressive CEDU school when she saw people sharing their stories of abuse in the early ‘10s: “My brand was more than my business; it was my identity, my strength, my self-respect, my independence, my whole life. I had to protect my brand. Anything off brand—no. Circle with a slash. Can’t have that.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-