Something Is Wrong in This House: How Bluebeard Became the Definitive Fairy Tale of Our Era

In DepthIn Depth

Image: Chelsea Beck

A door that locks without anyone touching it, rendering escape impossible. A large man who overpowers, beast-like. A man wears a mask of virtue that he removes behind closed doors. These striking and grotesque images could have sprung from fairy tales, but they didn’t—they’re from real testimonies by real women, over the last year of reckoning. Yet, there’s a kinship between so many #MeToo accounts and the original grimmer fairy tales that came before the 20th century.

In her short history of fairy tales, Marina Warner writes that the genre is remarkable for its straightforwardness: “This is as it is, as it happened; the tale is as it is, no more no less.” What has the past year been if not a parade of awful stories, delivered in clinical and straight-faced reporter speak? What is a whisper network but a series of people serving as each other’s fairy godmother? A father whose lusts are revealed to be perverse and violent describes both the Charles Perrault tale “Donkey Skin” and, in a sense, the man who was formerly “America’s dad,” Bill Cosby. Rape, assault, sexual harassment—they’re the stuff of fairy tales, fitting comfortably alongside the child-eating wolves and witches.

But of all the echoes of fairy tales, the loudest of all is the story of Bluebeard. The character, named for the color of his beard, originally appeared in Charles Perrault’s 1697 compilation Histoires ou contes du temps passe. Perrault tells the story of a rich, ugly man with a blue beard across his face who woos a young woman with a succession of parties at his elaborate home. The woman, often named Fatima, becomes convinced he can’t be quite so bad as a husband and consents to marriage. He gives her two keys, one of which unlocks all his treasures and she is free to use as she likes. The other, however, unlocks a small room that’s absolutely forbidden.

Of course, she unlocks the small room that’s absolutely forbidden. Perrault writes (via Norton’s The Great Fairy Tale Tradition):

At first she could discern nothing, the windows being closed, but after a short time she began to perceive that the floor was all covered with clotted blood that reflected the dead bodies of several women suspended from the walls. These were all the wives of Bluebeard, who had cut their throats one after the other.

She drops the key in her horror; when she tries to cover her tracks, she learns the key is enchanted and reveals the blood to her wife-murdering husband. “You wanted to enter the room! Well, madame, you shall enter it, and you shall take your place among the ladies you saw there,” Bluebeard thunders. The woman is saved from the fate of her predecessors, delaying her murder long enough for her brothers to ride to her rescue.

In the original telling, Perrault puts the fault at the heroine’s door, appending a moral warning against the dangers of a woman’s excessive curiosity: “Curiosity, in spite of its appeal, May often cost a horrendous deal. A thousand new cases arise each day, With due respect, oh ladies, the thrill is slight: As soon as you quench it, it goes away. In truth, the price one pays is never right.” Alternatively, it doesn’t take a Freudian to see lurking anxiety about marriage as the initiation into adult sexuality and the staggering rates of death in childbirth before the medical advances of the 19th century. But the most obvious lesson is quite simple: Before you climb onto the back of Prince Charming’s steed, remember that sometimes men murder their wives.

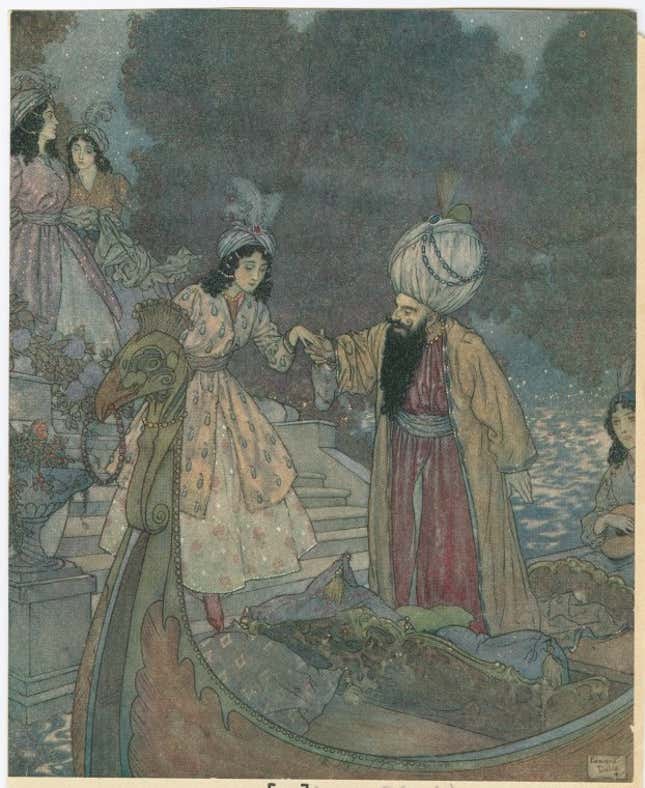

Bluebeard, though, has long been represented in a vastly different manner than the suitors of Cinderella or Snow White. “Well out of fashion in the court of the Sun King,” Warner explains in From the Beast to the Blonde, “the beard of Perrault’s villain betokened an outsider, a libertine, a ruffian.” Almost immediately, illustrators and retellers began interpreting that to mean that Bluebeard must be an Ottoman or some sort of Eastern amalgam, giving the story wildly Orientalist illustrations and pushing the whole disquieting tale into the geographic and cultural distance. (“By the blueness of his protagonist’s beard, Perrault intensifies the frightfulness of his appearance: Bluebeard is represented as a man against nature,” Warner adds—either by dying it “like a luxurious Oriental,” or by producing such a wild mane without any help.) This despite a long folkloric tradition associating Bluebeard with the very real Gilles de Rais, a companion to Joan of Arc, who was hanged in the 15th century for the serial murders of children. Even with this possible reality available, interpreters have imagined Bluebeard as fundamentally foreign, while representing the more appealing fairy tale husbands as familiar, even local.

Bluebeard has always been part of the fairy tale canon, but has drifted to the margins as “fairy tale” has come to mean colloquially something more specific than the “wonder tales” of Perrault and the Grimms. A “Cinderella story” is a generic concept obvious to everyone; we do not have the equivalent for Bluebeard. When Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s wedding was referred to as “fairy tale,” its meaning was apparent: an average girl turned princess living happily ever after with her prince. But unlike Cinderella, Bluebeard doesn’t lend itself to the Disney interpretation of the genre. A blood-smeared key and a string of dead wives stored in their own gore don’t make for little girl’s party decorations. Nor does it lend itself to the fanciful dress up of Disney femininity.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-