Image: Elena Scotti (Photos: Wikimedia Commons)

Anna Sewell’s Black Beauty (1877) is not often a novel that comes to mind when we think about Victorian literature. There are no youths entangled in agonized romantic longing, nor plucky orphans determined to distinguish themselves in a rapidly industrializing London, nor labyrinthine mysteries surrounding inherited wealth or parentage. No wives are imprisoned in attics (thank goodness), and nobody wears a decades-old, moldering wedding dress to mourn the lover who jilted her at the altar. These are the sorts of stories we tell about people, and Black Beauty is the story of a horse.

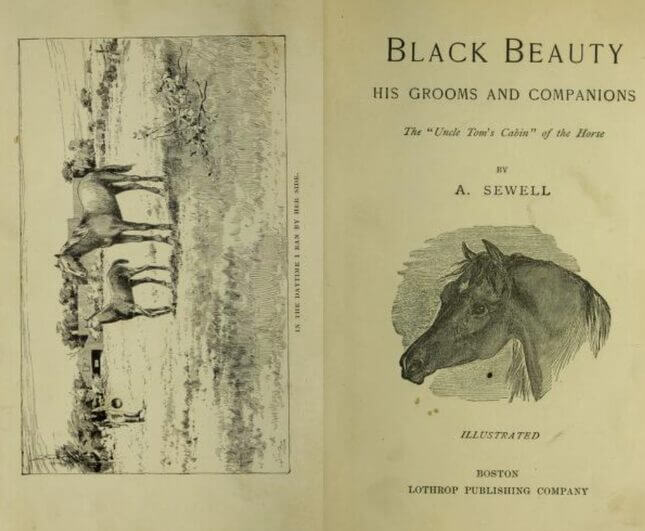

Sewell, whose bicentennial is on March 30 of this year, named her first and only novel Black Beauty, his grooms and companions; the autobiography of a horse,‘Translated from the original equine by Anna Sewell’—and as the rather verbose title suggests, the story is narrated in first person, by Black Beauty himself. It chronicles the ebb and flow of his fortunes, from an idyllic colt-hood to a happy, plush situation amongst benevolent rich folks, to the afflictions of hard labor and abuse. “I am writing the life of a horse,” Sewell declared in an 1871 diary entry, explaining that her motivation was to “induce kindness, sympathy, and an understanding treatment of horses.” This decision to write from Beauty’s perspective was a profound exercise in empathy, and while it might seem like an obvious choice to those of us who grew up with Charlotte’s Web and Frog and Toad, Victorian readers were less accustomed to books that featured talking animals. Surely, an animal narrator was even more of a surprise. With rare exceptions, like Francis Coventry’s 1751 novel The History Of Pompey The Little, fiction remained a province of human experience.

Black Beauty’s novelty must have worked in its favor because it was a prodigious success. Jarrod & Sons paid Sewell a meager £20 for the rights to the book; it was published on November 24, 1877; and by 1890, it had sold over 200,000 copies. Sewell, however, never saw her book become a literary juggernaut, nor did she enjoy any financial benefits: in April 1878, she died of hepatitis, shortly after her 58th birthday. Black Beauty had only been on the market for five months; certainly, there was no way to know that her manifesto on animal rights—modest and green, a sketch of horse gazing woefully from its cover—would become one of literary history’s best-selling books. It has never once gone out of print.

Black Beauty is typically categorized as children’s literature, and although Sewell did not write with a young audience in mind—she hoped to reach those who worked directly with horses—the taxonomy makes sense, and it calls to mind the skepticism we so often direct at imagined animal subjectivity. Stories featuring chatty animals tend to be treated as whimsical and fairytale-adjacent; they demand suspension of disbelief in a way that adults are less inclined to indulge. Sometimes my own intolerance on this front feels like a personal limitation, an unwillingness to dwell in the pleasure of fantasy—and, moreover, to extend my empathy to that length. Generally, I prefer my animal-centric media and literature to be winkingly clever: Zootopia instead of, say, Bambi. I am asking for my fragile adult ego to be soothed and validated, for the film or book to insinuate that it knows that I know we are frolicking in impossible fiction. I would rather feel intelligent for understanding the way a trope is manipulated than give myself over to an earnest anthropomorphic narrative that isn’t interested in either meta-jokes or appealing to cynicism.

But regardless of the story’s tone, hyper-articulate animal characters like Black Beauty are an oft-welcome presence in children’s media; after all, fanciful conceits can mitigate the tedium of didacticism. It’s no surprise that children’s literature, particularly from the Victorian and Edwardian periods, veers towards the morally educational. In 19th-century England especially, it was a handy mechanism for breeding loyal, Christian British subjects. And over time, writers like Beatrix Potter (The Tale of Peter Rabbit), A.A. Milne (The House at Pooh Corner), and Arnold Lobel (Frog and Toad) have sought to instruct through gentler, more compassionate means. That said, Potter’s bucolic tales can be singularly harrowing, even disturbing. I’m pretty sure that reading The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck as a little girl did more to exacerbate my existential anxiety than to instill good sense.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-