In Ballet, Pain Really Is Beauty

"I wanted bunions, blisters, bleeding toenails, and I envied the girls who bruised more easily," Alice Robb writes in her book about being a child ballerina.

BooksEntertainment

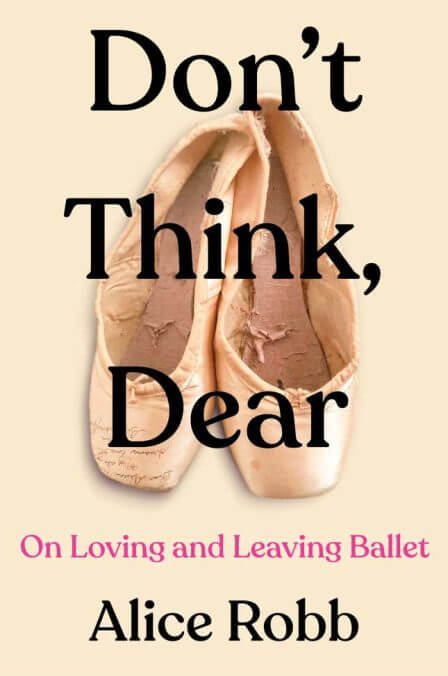

The following is an excerpt from Don’t Think, Dear: On Loving and Leaving Ballet by Alice Robb, which came out on Tuesday. You can buy it at Bookshop and Amazon.

Throughout our lives, women suffer from all kinds of extra pain. We have more nerve receptors than men and, literally, thinner skin. In the lab, women exposed to the same electric shocks and hot and cold stimuli register more acute pain. From the time girls learn where babies come from, they anticipate the pain of giving birth. From puberty through middle age, women risk cramps, migraines, nausea, and muscle aches every month. Pain is often a facet of girls’ sexual initiation, and many just accept it. “The sex was always painful but I thought that perhaps that was the price of being loved,” the sex worker Liara Roux writes of her first romance. In a survey (described in the Journal of Sexual Medicine) of over 1700 men and women in the United States, 30 percent of women say they experienced pain the last time they had sex, compared with just 5 percent of men.

The most common response to all of this is to grit our teeth. In her memoir Sick, the writer Porochista Khakpour reflects on a lifetime of physical and mental anguish—and on how her identity as a person in pain has been intertwined with her identity as a woman. Growing up, she looked forward to getting her period—“the affliction that it seemed everyone I knew got to complain about.” When she fainted after emerging from a too-hot shower, at the age of 13, it felt, on some secret level, like a longed-for rite of passage, a fast-track ticket to fulfilling her gender identity. It was also, she wrote, “the first time I got to feel like a woman”—and the dawning of her realization “that perhaps ailment was a feature central to that experience.” Dainty and fragile, she felt like an ideal woman—“like a crystal ballerina.”

No one embraces pain more fully than dancers: the pain of contorting their bodies into impossible shapes—twisting the legs to turn outward from the hips; forcing the weight of the entire body onto the tip of one toe, then hopping up and down on that toe. The pain inherent in whittling their bodies into the toothpick figure [New York City Ballet choreographer George] Balanchine preferred.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-