At the end of April, the actor and activist Alyssa Milano went on MSNBC to talk about Joe Biden and the presidential election. Halfway through the interview, she shared her strategy for the Democratic Party. “This primary to me is not about policy. It’s about beating Trump, period,” she told the hosts. “That’s it, end of story.”

Milano continued, bluntly punctuating her point: “It’s not about who’s going to make the best president.”

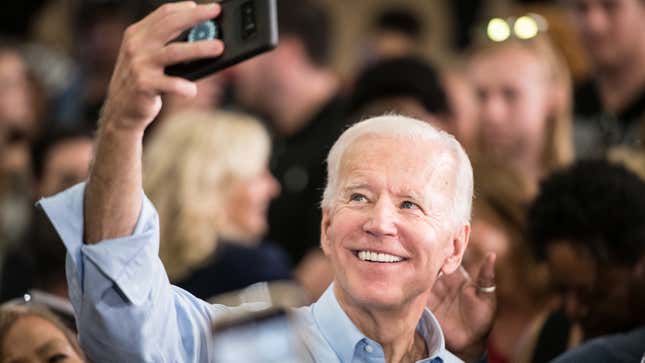

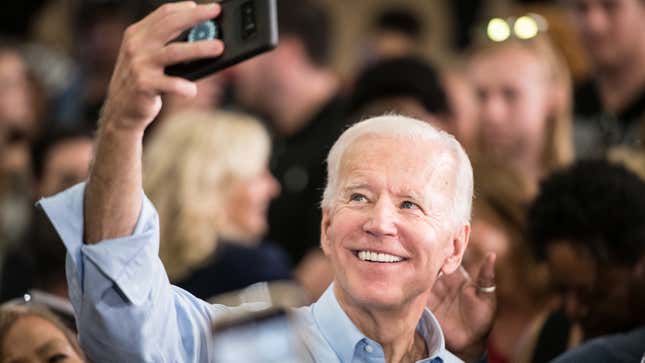

That sentiment neatly captured the central, perhaps only, promise of Biden’s campaign: that he is the Democrat best positioned to defeat Trump, a calculus that many voters have embraced. “I like Elizabeth Warren’s policies, I just don’t think she can get elected,” Greg Reed, a 72-year-old retired high school principal in Iowa, told the Los Angeles Times shortly after Biden announced his candidacy. “I believe Biden can win. That’s what I’m interested in. Beating Trump.” Perhaps, you, like me, have heard similar sentiments from friends and family members, and have wanted to rip your eyeballs out and burn them in a pyre.

Welcome to our electability conundrum, where the carefully cultivated narrative of one’s ability to win in 2020 has become the main metric by which to judge a candidate’s merits. If in 2016 we were subjected to endless takes on whether Hillary Clinton was “likable” enough to win, today, “electability” has become the new likability, which of course, was always just a fraught gendered code-word for the idea that white men with milquetoast politics are best positioned to win. (Except when they don’t!) It is, as the historian Claire Bond Potter recently noted, “a standard that history shows us was created and sold by men.”

“Electability” has become the new likability, which of course, was always just a fraught gendered code-word.

In 2016, we were told that Trump’s victory threw all of our previous ideas of who might be electable out the window; last year’s midterms were supposed to mark a referendum on politics as usual—a sign that women, and in particular women of color, were on the rise. So it’s all the more curious that as we look towards 2020, “electability” has become a coded directive, offering us the same candidates that until the very recent past, we have been used to getting—bland, centrist white men in the vein of Al Gore and John Kerry, both of whom, it shouldn’t need to be said, lost.

As Pete Buttigieg is celebrated in the media for his Midwestern roots and his intelligence, Beto O’Rourke for his ability to inspire devotion (at least until recently), and Biden for being the pragmatist next door who can win blue-collar workers, the women running, not to mention the men of color in the race, have yet to break through on similar grounds.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-