The hot A train is packed with post-workday commuters, and by the time I reach Tribeca it is happy hour. Suited professionals are spilling out from office buildings and into the many bars of the neighborhood. I walk past the same Irish pub three times before finally checking Google Maps; I am new to New York, and easily lost. The dergah, or house of prayer, I am looking for sits between an outdoor Italian bistro and a pop-up cocktail bar, marked only by a small sign that I don’t see until I am right outside its door.

I am already running late. I wasted 30 minutes in Anthropologie’s sale section, looking at cotton scarves and printed stoles, anything I could wrap around my head for modesty. I finally gave up and arrived at the dergah bare-headed, prepared to feel uncomfortable and underdressed. Growing up Muslim, I knew that I must cover myself up before entering a mosque, and I anxiously assumed that the dergah would have the same rule for women visitors.

When I arrive, the large carpeted room is already full of worshippers. Women with bare and uncovered heads are everywhere, alongside women with scarves wrapped loosely over their hair, women in full hijab. Women wearing short sleeves, women in kurtas, and in t-shirts. Women with their children, women alone, next to men, next to me, everywhere. My anxiety dissolves.

This Sufi dergah is like no other mosque or prayer space I have ever been to in my life. The sheikha, the leader of the entire community, is a woman. Many of the muezzin, who perform the daily call to prayer, are women. Muslim women leaders are generally rare in my experience, and women muezzin are even rarer. But here, I watch women occupy community space as freely and comfortably as men do. Some women lead the prayer, and some women lead the kitchen staff that cooks dinner for the entire community.

I talk to one regular, Maryam, a born-and-raised New Yorker who has been visiting the dergah for four years now. “I’m sure if you’ve been to a mosque, you’ve heard of somebody saying ‘your hair is not covered enough,’ or ‘you’re wearing nail polish,’ or whatever the reason is,” she tells me. I nod in agreement. This is why I was late, after all.

“As women, we spend a lot of time hearing a lot of those types of things. So to just be in a space where you don’t have to hear those things, and also feel like we’re accepted and included in the main prayer space? There’s no separate women’s space [here], there’s just the prayer space for all beings.”

The separate women’s space Maryam refers to is a common fixture. Most mosques separate visitors based on gender, at least in some capacity. Even the Muslim Students’ Association at my liberal arts college placed women at the back of the prayer room.

The men’s section is usually the main section of the mosque, closest to the imam leading the prayer up front. The men have room to spread out and pray comfortably. The women’s section is often in the back, or in a dimly-lit room off to the side, where we may not be able to hear the imam at all. It may be up a flight of rickety stairs, or present other barriers to physical accessibility. Women are crowded together, pushed practically on top of each other when we kneel.

My experience with the women’s section is one of the main reasons why I don’t attend prayers at mosques more often, or at all

The intention of a women-only space may sound noble in theory, especially stripped of its context: a place for women to pray comfortably, without the male gaze. The Quran itself does not require gender segregation and encourages men to “lower their gaze” when interacting with women. But historically, quarantining Muslim women of out general public spaces became a way to more strictly police their actions. In practice, the women’s section is often ill-maintained and under-resourced; another way to place us in the back and out of sight. Gender segregation of any kind also reinforces the false gender binary, turning the mosque into an unwelcoming space for gender non-conforming or non-binary worshippers. My experience with the women’s section is one of the main reasons why I don’t attend prayers at mosques more often, or at all.

“You know, there’s all these jokes about women in traditional Islamic settings in the U.S., or anywhere, praying in broom closets. And I’ve definitely experienced that,” Maryam tells me. “Just the access and the ability to hear properly in [the dergah] was really profound and great. I’ve been in a lot of spaces where women were listening via a mic, or with poorly done acoustics, and sometimes it was very hard to feel connected to the prayer. So this was really lovely, to have an experience just be so inclusive.”

At the Tribeca dergah, there is only the one main room, where I sit. When it is time to begin the prayer, all the worshippers turn east towards the Kaaba in one synchronized movement. Toddlers chatter in the back or weave through the praying crowd. A young girl taps her father on the head as he leans down to touch his forehead to the ground.

My head is uncovered, and I am no longer berating myself for forgetting to bring a scarf. My arms are bare, my nails are painted, and my body is mine. I sit in the back to watch, still a little unsure of my place, but the prayer is loud and sweet, and I can hear nothing else.

The room opens itself up.

The second time I visit the dergah, it is the last night of Ramadan. The room is somehow even fuller, buzzing with quiet whispers. I feel the kind of childlike excitement I always do the night before Eid, even though I am alone in the city and don’t have family to celebrate with this year. Next to me, a baby fusses in a carrier, her parents sitting with bowed heads. A young boy, somebody’s son, steps carefully through the crowd with an enormous bowl of dates. Another adolescent offers me a paper cup of mint water.

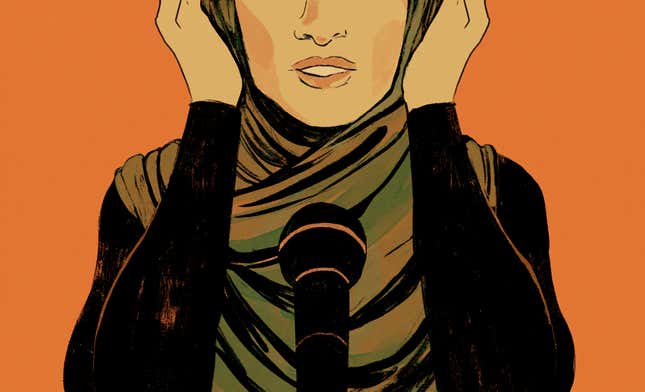

I wait for the azaan to begin, the call to worship that marks the beginning of prayer. A tall woman in a green scarf walks to the front of the room, and the whispers stop. Her voice fills up the quiet, carrying all the way to the back where I sit between two teenagers. The words are familiar, I have heard them a hundred times over. But for the first time in my entire life, I hear a woman performing the call.

Women muezzin are rare. Like most positions of responsibility in the mosque, the role is usually given to men. To have a woman take on this loud and vocal act is hugely important; it is a public acknowledgment, finally, of the risk and responsibility that Muslim women are constantly burdened with both inside and outside our community.

At its core, the azaan is an announcement informing Muslims when it is time to pray. It holds cultural and aesthetic significance, but in this climate of bigotry and violence, when mosques are constantly being targeted with hate crimes, the azaan takes on an added weight. It is a highly public symbol, which has been cited by bigots as evidence of a supposedly intrusive Muslim presence in many countries, including the United States. To Islamophobes, it sounds like an invitation for violence.

For a woman to walk to the front of this room and flood it with the sound of her voice is an incredibly powerful act. Muslim women, who face racism and Islamophobia from outside our community, proclaim loudly “We are here.” Muslim women, who also face sexism and misogyny from within our own community, proclaim even louder: “And we belong here.” Sitting there with head bowed and hands cupped in prayer, I find myself tearing up at the sound of this woman’s voice giving the azaan.

The words are familiar, I have heard them a hundred times over. But for the first time in my entire life, I hear a woman performing the call

The first woman I hear, Gulrez, is a young Turkish woman who now lives in the United Kingdom. Her voice is strong and powerful during the azaan, but when she sits down to talk with me, she speaks softly, barely above a whisper. I have to ask her to speak up to make sure my recorder catches her words.

“I wanted to use my voice,” she says when I ask her why she first volunteered for this job. “But the thing is, even if I wanted to, and I had this desire, the practice asks me to be humble about it, and to kind of wait my turn. So at some point […] there was an opportunity and I said, sure, I can, if we’re looking for somebody to call the prayer. And so I did.”

The azaan is not just an exaltation of God. It is distinct from prayer, which is addressed directly towards a god. The azaan does not gaze upwards towards heaven, but looks sideways towards one’s people. It is a calling out to fellow worshippers, urging us all to join in prayer. As I understand the azaan in my own experience, it is simultaneously an act of leadership over a community, and an act of service for that community.

But none of the women I speak to describe it as a leadership role, only as a way to volunteer their voice for the good of the community. I am told repeatedly that performing the azaan is just a contribution towards the community, a way to help out. There is something familiar in this insistence, this refusal of power. It reminds me of my mother and grandmother—women who run the house but would never call themselves head of the household.

I speak with Zhati, another regular who I notice serving food to visitors and herding young children around the dergah. “It’s not about who is leading the azaan, or who’s leading the dhikr,” Zhati tells me. “[…] It’s about who is invested in the community, and who [are] invested in sacrificing so that the community can prosper.” When I first saw Zhati, I assumed she must be one of the community leaders. And maybe this is a new definition of leadership; in sacrifice, in service.

Zhati says the community has been incredibly supportive of women giving the azaan. “The brothers have been more trained in it, because of just how things are. So they know more Quranic verses and they’re more experienced with it, you know?” she says. “They have been very supportive and helpful, they kind of take us in and try to teach us. They’re kind of rooting for us, as we’re leading the prayer, we feel their presence there.”

Despite the support from within, the dergah is still careful, still wary. Zhati tells me about the big Friday prayer, hosted by the dergah and attended by the local Muslim population of Tribeca. “There aren’t very many masjids [mosques] in lower Manhattan. And there is a large Muslim community there—of vendors, and shopkeepers, and people that need to come for jummah [Friday prayer]. If we weren’t offering that service, then many people would have to just pray outside, on cardboard, on the streets, you know?” she says. “We offer that a service to the Muslim community, and they are comprised of people that perhaps are not as exposed to the dervish teachings and Sufism. And because of that, we want them to feel comfortable and welcome. So during the jummah, men lead the prayer, and men stand in the front, and women have a section at the back.”

The decision to follow a segregated practice for Friday prayers comes from a desire to keep the dergah an accessible space for the local population. “You know, the adab calls for us to be hospitable,” Zhati reminds me. “So we don’t do that, because it’s not something that I think the more mainstream Muslim community in Tribeca would be used to.”

Muslim women, who face racism and Islamophobia from outside our community, proclaim loudly “We are here.” Muslim women, who also face sexism and misogyny from within our own community, proclaim even louder: “And we belong here.”

If there is a “mainstream Muslim community” in Tribeca, then what would this dergah call itself in comparison? The phrase “progressive Islam” has been thrown around a lot in recent years, but the women I speak to are firmly against this term. “[The word] ‘progressive’ is like a box,” Gulrez says. “It sounds as if there is a progressive Islam, and there is a backward Islam […] That’s not my experience, because to me what we’re practicing is part of the Quran, is part of the sunnah. So to say ‘progressive’ is too limited and limiting.”

This limited navigation of Islam has been around since the post-9/11 resurgence of Islamophobia, and maybe even earlier. It reminds me of the enduring myth of the “good immigrant” who successfully assimilates, that was created in opposition to the supposedly “bad immigrant” who is criminalized in comparison. Similarly, the label of “progressive Islam” valorizes some of the ways Muslims embody their spirituality, specifically those lifestyles that most easily blend into white Christian American life—particularly since the label of “progressive” is usually handed out by white America.

Many Muslims, and especially young liberal Muslims like myself, feel pressure to perform Islam in a more digestible, secular way that aligns with the image of “progressive Islam.” We fear that if we do not perform well enough, we will instead be placed into that other category of “regressive” Muslims. These Muslims are labeled backward, shamed for not meeting the standards of modern liberalism laid out by white America.

This is not to deny the sexism is still deeply rooted in many Muslim communities, a thick and gnarled root that stretches and twists through our families and spaces. I have faced sexism from brown Muslim men, just as I have faced sexism from white Christian men. I have seen patterns of gender inequality in brown Muslim communities, and at my predominantly white liberal college, and in the American workforce, and everywhere. The sexism I face from brown Muslim men is sometimes unique—justified by the use of scripture and spirituality. The sexism I face from white Christians is unique, too, when it intersects with racism and xenophobia.

But there is a crucial difference between me, a Muslim woman, critiquing my community from within, and white America laying claim to that critique, using my experience as evidence to push Islamophobic politics.

In rejecting the progressive versus regressive binary, the women at the dergah refuse to be turned into evidence. They decide how open, free, and equal their own community is. They set those standards, and decide how well the community is meeting their needs. The conversation belongs to them, just as the room does.

“This is actually not ‘progressive,’ this is the original,” Zhati explains when I ask her about the dergah’s practices. “The Prophet Muhammad […] he came as a mercy to all the world, he came for every human being. He didn’t just come for a small section of people in Saudi Arabia. He came for the gay people, for the straight people, for the women, for the men, for the young, for the old, for the people of today, and the people of 1400 years ago. He came for all of us, you know? So this was his original vision, this vision of social justice, of inclusivity, of equality.”

The framework of a return to an original Islam, rather than a forward progression towards white American feminist liberalism, seems essential here. These women suggest a way to reclaim Islam from contemporary patterns of sexism. In rejecting the allure of progressiveness altogether, they suggest to me a new way to think about my own Muslim identity in America.

Although I place great weight on the importance of rhetoric, for the women of the dergah, equality seems to be self-evident. When I ask Maryam about the issue of gender equality, her answer is almost a verbal shrug. “I like the fact that it’s not highlighted, it’s not really dwelled upon, it’s not made into a big thing. That’s just the way it is,” she says. “In terms of who gives the azaan, it’s really whoever is available at the moment, and is there, and ready, and would want to say it […] It’s not really highlighted on gender. At the same time, it is really profound, because it is not something that happens in other spaces. So to hear a female voice saying the azaan is really beautiful, and a commitment to an inclusiveness for everybody.”

There is a crucial difference between me, a Muslim woman, critiquing my community from within, and white America laying claim to that critique, using my experience as evidence to push Islamophobic politics

It is thrilling to hear that the decision towards inclusion was such a natural one in this community—so commonplace that it need not even be highlighted. Equality is self-evident, and it should be natural. Of course Muslim women should be able to take on leadership positions. Of course we should be able to pray in clothing that is comfortable and convenient. Of course we should be able to maintain a personal and private relationship with our God in whatever capacity we choose.

But these truths are so often obscured by insidious misogyny within our community. It is hidden out of sight in women’s spaces or brushed away with excuses of tradition until even the smallest move towards equality seems like a rare and precious gem; it seems miraculous that a place like the dergah even exists.

Maybe this is why the women of the dergah are so protective over the space. This is a place of worship, I am reminded again and again. This is not a place for writers and journalists—although I am one of those, too. I understand the desire for privacy, from the close scrutiny placed on Muslim communities, and especially on us as Muslim women. I have often been turned into an unwilling spokesperson, questioned on what Islam means for us all. I have been asked whether I was or was not ever pressured by family to wear the headscarf; whether I do or do not find the community regressive; whether I can or cannot defend Muslims from Islamophobia without first defending women from Islam itself.

When Gulrez is quick to tell me that her parents never made her wear the headscarf, I understand. When Maryam says she is usually hesitant to talk with journalists, I get it. Our spaces have been taken away from us for so long. Even before 9/11, when spies started infiltrating mosques to fill the cells in Guantanamo. Even before mosques became targets for arson, bomb threats, pig’s blood. It has always felt like an almost impossible task for Muslims to find safe spaces, and this stands doubly true for Muslim women.

I sit with Gulrez on the carpeted steps leading up from the main room of the dergah. Below us, community members prepare the space for the dhikr ceremony that will happen later tonight. Above us, visitors are still finishing up the iftar meal, breaking their fast with homemade lamb curry and quinoa.

On an especially busy night at the dergah, this is the only space we have found to talk. We huddle close together over my phone, which I hold up to capture Gulrez’s soft voice. She has just finished telling me about her family, her upbringing, how she rebelled against religion when she was 12 or 13, how she rediscovered her spirituality in her late-20s. I forget myself, share stories about my own life growing up Muslim. The opportunity to speak with someone who has such a similar experience to mine is so rare, it is too sweet to pass up.

“Did you do any training before giving the azaan?” I ask her, and she shakes her head no.

Just then, the chatter from the room above cuts off. The chanting of the dhikr begins, a multiplicity of voices growing louder in unison. Gulrez, who has so far been restrained and quiet, now grins widely. “I’m going to want to participate in that, using my voice,” she says, laughing. The chanting has filled the stairwell now, and she gets up and drifts away to join the ceremony.

I sit silently for a moment and let the chorus of voices wash over me. Then I follow.