In The Raft, 10 Human Guinea Pigs Stop Being Polite and Start Getting Real… On a Boat

EntertainmentMovies

Image: Array

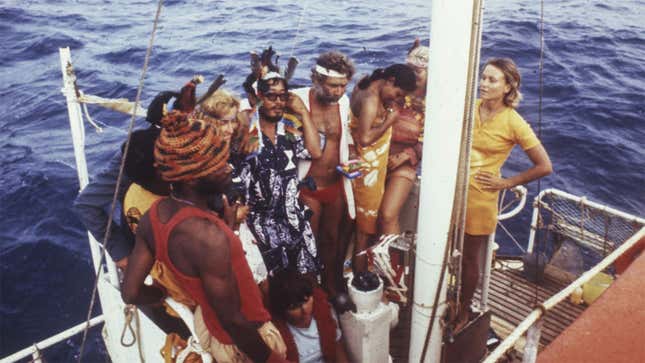

In the early ’70s, Santiago Genovés was an anthropologist from Spain with the manipulative mastery of a modern-day reality TV producer. In what became his most notorious experiment, in which he collected 10 people to live on a small boat named the Acali as it slowly floated from one end of the Atlantic Ocean to the other, he saw the subjects of his social experiment as “basically a microcosm of the world.” They were selected from varying backgrounds, hailing from such countries as Uruguay, Cyprus, Sweden, Mexico, and the United States, “to create tensions.” He let them have no outside entertainment—not even books—and forced them to rely on telling stories and singing to pass the time. He placed them in a dangerous situation to provoke their instincts, and when they didn’t deliver the drama he craved, he attempted to turn them against each other by reading out loud things they’d written in confidence. The man was a drifting ethical violation.

At least, that’s how he’s portrayed in Marcus Lindeen’s riveting documentary The Raft, which opens Friday in a handful of theaters (including New York’s Metograph) and will continue to roll out across the United States throughout the summer. The Raft hits several sweet spots as both a tale of wacky ’70s thinking and also a way for many of the crew’s surviving members (almost all of them women) to reclaim their narrative. If it were streaming on Netflix, it’d almost certainly become the latest in a long line of that platform’s crazes. It is, at any rate, worth seeking out.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-