Margo Price Surveys Her Own Destruction

Between her memoir and new album, the singer-songwriter is incapable of telling anything but the truth about years of affairs, addiction, and darkness.

EntertainmentMusic

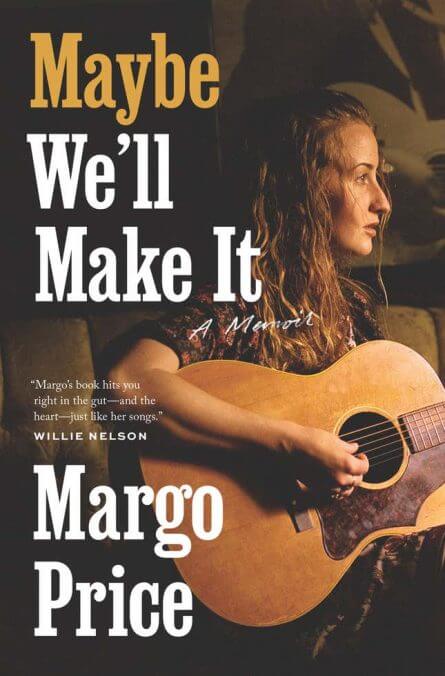

Photo: Alysse Gafkjen

Margo Price doesn’t give a fuck. At least, that’s what every publication on both sides of the Mason-Dixon has said of her since 2016, when her debut album Midwest Farmer’s Daughter arrived to critical acclaim for its plucky, purposeful take on country music. She’s a “badass,” a “Nashville rebel,” and an “outlaw.” “Unstoppable, unsinkable, and uninhibited,” even. If you judged the Grammy-nominated singer-songwriter and memoirist by her artistry (a sort of plain-speaking poetry) or latest tattoo (you belong to no one on her forearm), you might make the grave mistake of assuming she couldn’t be bothered by your perception of her. But, by her own admission, she’s a person who reads the comments. And she does give a couple of fucks, by the way.

“I get really frustrated when I’m just trying to be a writer and a musician, and I feel like people are…” Price pauses during our Zoom conversation last week, then references an Instagram post of her recent New York Times interview. “The comments on the Instagram post are just like grenades waiting to be set off. I don’t understand why these people are talking about the way that I look, because I’m a writer. I don’t know how that has anything to do with anything.”

Price has already given people plenty to talk about (and unfortunately, this occasionally includes tired comparisons to Sarah Jessica Parker and barbs about her Streisand-esque profile). It would be an understatement to call her poignant, pulverizing memoir, October’s Maybe We’ll Make It, soul-baring. Price practically plops her heart, spleen, and a couple of kidneys onto the page. Maybe We’ll Make It has been called “brutally honest” and lauded by the likes of Willie Nelson and Lucinda Williams for its heartrending anecdotes of addiction, affairs, and aspirations that cost an already-broke artist a lot more than her car. Then, Price sauntered into 2023 with the self-assurance of someone who’s seeing the fruits of nearly two decades of labor by releasing her fourth studio album, Strays, on January 13. The ten-track record follows the 39-year-old mother of two into newly revelatory territory with her husband and collaborator, singer-songwriter Jeremy Ivey. Strays plays like an auditory upper with its proud first single “Been to the Mountain” (I just know who I’m not, man, that’s alright with me), and a downer, as with the mournful “Hell in the Heartland” (Love gets you hurt, bein’ real gets you hated).

“I wanted the entire album to be like this psychedelic trip from beginning to end that could also just be like a lifecycle of somebody. Through it, there’s going to be incredible high moments and moments of euphoria and bliss and joy. And then, of course, there’s going to be some really dark times,” Price says.

Unlike past records—namely, 2020’s That’s How Rumors Get Started—Strays at its best moments isn’t quite a pound-for-pound reflection on her life, but a fluid rendering of anyone she’s met along the way. On “Lydia,” for instance, Price sings right to a young woman weighing the cost of an abortion: Just make a decision, Lydia, just make a decision/It’s yours.

“That song came to me in a very mystical way, and songs don’t often come to me like that. Most of the time, it’s a lot more work,” Price says. “It was just incredibly dark—I’ve written a lot of dark things before, but they were kind of hidden in this major key. This is just pure darkness.”

I thought for a really long time that there was like, this magic in being a hot mess—like I’m fucking Bukowski or something. I need to destroy myself in order to make good art.

Price sat on the song for three years, then decided to release it in November, five months after Roe v. Wade was overturned. “Living in a red state [Tennessee] and like, raising a daughter in this time when women’s health just seems to be this hot button topic and something that we’re not even allowed, I knew that it was time that it was heard.”

Since her debut, she’s been dubbed a truth-teller incapable of holding her tongue even if she tried, inviting comparison to predecessors like Loretta Lynn and Emmylou Harris. Lately though, Price isn’t just telling the truth, she’s examining it—on Strays, through the narratives of other beleaguered Americans, and in the case of Maybe We’ll Make It, through her own. In fact, Price is so exposed in the latter that it might seem as if she doesn’t mind being the kind of anti-hero who would keep Taylor Swift in her copper-colored coffin. There’s the affair Price had with her bandmate (“the Fleetwood Mac part of the tale,” she says), the grief she’s survived following the death of her infant son Ezra, and her fraught relationships with alcohol, the country music industry, and, pre-Midwest Farmer’s Daughter, gainful employment. Price tests her audience’s empathy, doing what so few artists in country music and the industry writ large do: allowing herself to be thoroughly unlikable. But that hasn’t come without effort. When she gave an early draft to friends to read, those who know her best sensed Price was holding back.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-