One Mistake Won't Ruin Your Life. Remember That.

Latest

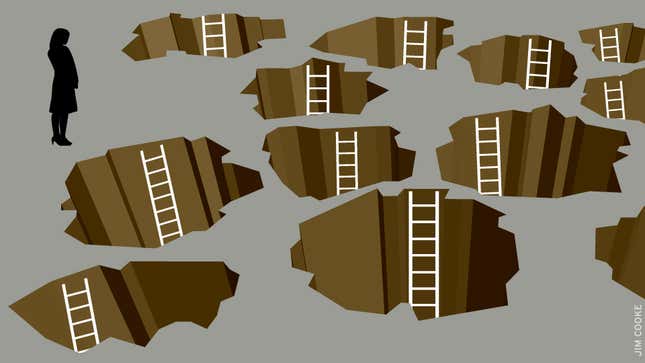

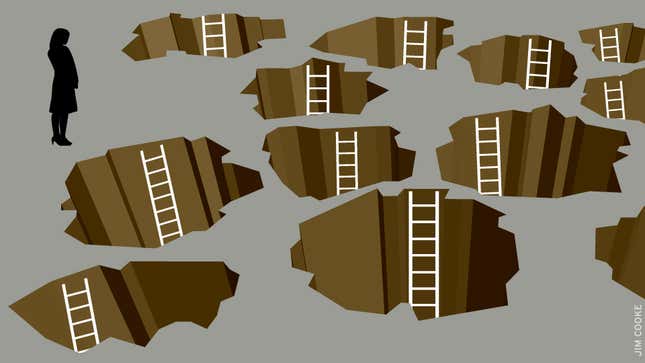

One mistake will ruin your life. For generations, adolescent girls have heard that message over and over from mothers, fathers, grandparents, teachers, pastors, rabbis, and busybodies galore. Whether the warnings are about getting their hearts broken, losing their oh-so-precious virginity, or –- worst of all –- getting pregnant, the admonitions are urgent, repetitive, and (even when they’re ignored) effective at instilling anxiety and self-doubt. Girls born as recently as the 21st century are taught that adolescence and young adulthood consists of a series of pitfalls to be avoided, and that one false step could mean a lifetime of heartbreak and regret.

This “do one wrong thing and you’ll pay for it forever” narrative isn’t just tied to perennial parental fears about high school pregnancy. Regrettably, it’s become one of the primary lessons of the Amanda Todd tragedy. Less than three weeks after the Canadian teen killed herself, her story has been hijacked to serve as a brutal object lesson about the lethality of a single lapse. In the Examiner, Angela Gaines writes “I’m sure she never fathomed what could happen to her as a result of that unforgettable few seconds of her life, but now we all know… This story is one sad example of how a life was blown to bits because of one regrettable indiscretion.”

Gaines’ piece is itself “one sad example” of the way in which Todd’s suicide has been appropriated in the service of victim-blaming slut-shaming repackaged as concern for vulnerable teens. It’s hardly the only one; a story this week on Emoderation carries the URL “Young People’s Lives Ruined by Sexting Images.” The report itself isn’t alarmist, simply warning of the very real likelihood (88%) that a naked image sent privately will end up in the public domain sooner or later. Research shows boys and girls sext in nearly equal numbers. The problem isn’t gendered. But the hand-wringing rhetoric about “a life blown to bits” is directed almost exclusively at girls.

It’s easy for girls to internalize this message. In her powerful story about being bullied into making nude webcam videos when she was 15, “Anonymous” writes of the pain of her parents’ disappointment. Despite her interest in theater, she decided that “a career as a musician or actress were completely out of the question. A job in the public eye could be ruined over a mistake I made at a young age.” No doubt Anonymous believes what she wrote. Yet given the great and growing number of celebrated actresses with nude pics or sex tapes in their pasts or presents, her fear seems grounded less in objective truth and more in culturally-reinforced anxiety about what “one mistake” can do.

The heartbreaking tragedy of Amanda Todd fits all too well into the larger cultural narrative that demands perfection from girls. Her “error” serves as a very public stand-in for all the other possible mistakes young women can make that will, we tell them, mess up their lives. The perfectionism that drives young female athletes to ignore warning signs of injury much more consistently than their male counterparts (a growing phenomenon documented in Michael Sokolove’s Warrior Girls) reflects a belief that admitting fragility or exhaustion is a mistake that can both ruin a soccer career and reflect badly on their future chances of success. The “Supergirl crisis” is far from over-hyped, made worse by a culture where male underachievement just exacerbates the pressure ambitious and anxious girls already feel. The end result is a cruel double-bind: “you can be anything you want to be,” we tell our daughters, “but you’re so fragile that a single mistake can wipe out everything you’ve worked for.” That’s a recipe for exhaustion.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-