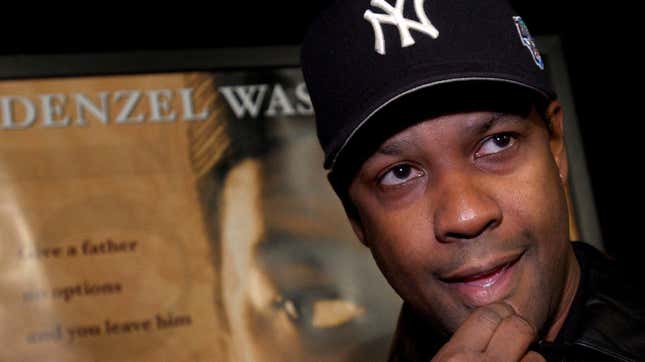

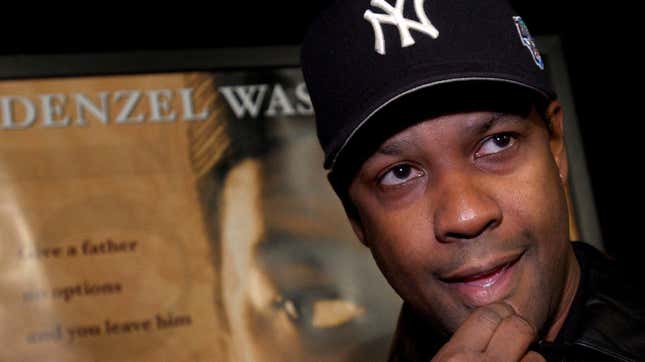

One way to measure a movie’s success is by who it offends. And as it turns out John Q., a cheesy Denzel Washington vehicle about a man who remedies a surprise medical bill with a gun, didn’t particularly impress reviewers or healthcare officials when it was released 2002. Hospital administrators called it a “one-sided caricature of healthcare” and a work of “pure Hollywood.” The Baltimore Sun took issue with the “demonizing of the managerial class (and the idolizing of the working class)” expressed by the script. Dr. Oz, who had consulted on the production, appeared in the New York Times post-release to note he was actually somewhat offended by the film’s caricatures of cold-hearted hospital staffers more concerned with purse strings than public good: “There is no bad guy in this system,” he said. “Insurers have defensible reasons for what they do.”

John Q. is about as heavy-handed as you might expect a movie to be when its title character is named after a historical shorthand for the common man. The characters—a bad cop, a good cop, an angelic youngster, a dad full of conviction and verve—aren’t so much complex people as foils for an aggressive moral arc. But if you happen to be into movies like Die Hard and think the American insurance reimbursement system is full of shit, it’s an immensely satisfying experience, a big-budget blockbuster toggling between the kind of hostage plot that defined the late ’90s and punchy explanations of the business of kickbacks and premiums. As I’m sure this must have been pitched at one point in some Hollywood conference room: just imagine Speed, but if the extortionist strapped with a bomb was the medical system at large.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-