Film is a trickster’s medium, an illusion of an illusion. Though it purports to capture objective fact—as if holding it for ransom—there are few things as subjective as a frame. “It is said that the camera cannot lie,” wrote James Baldwin in The Devil Finds Work, “but rarely do we allow it to do anything else, since the camera sees what you point it at: the camera sees what you want it to see.”

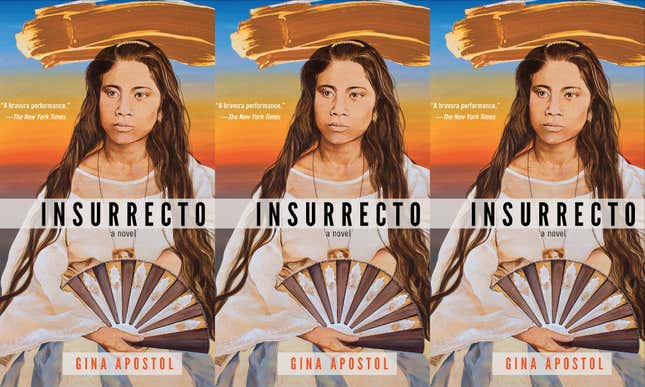

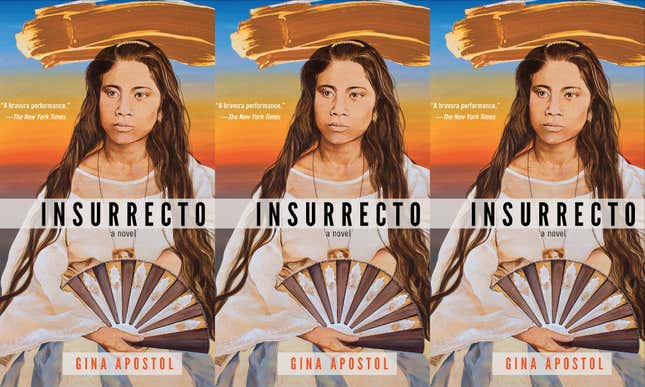

Gina Apostol’s novel Insurrecto is a tale of dual visions and dueling scripts, one written by an American filmmaker, Chiara Brasi, and the other by a Filipino writer and translator, Magsalin. Magsalin isn’t given a last name, and this reader suspects that her first is a fake one: magsalin, we are told, means to translate in Tagalog. She is what she does in the eyes of the white foreigner, what she does for her. Translation is a precarious occupation, a profession historically populated by people in slavery or servitude who, defeated by enemy armies, were forced to interpret their native language for the benefit of their captors. These translators’ relationships—to language, to nation, to family—were uneasy ones, and conquerors tended to view these natives-made-other, these double-tongued strangers, with suspicion. This mistrust lingers, still, in the Italian idiom: traduttore, traditore. Translator, traitor.

Keep that in mind when I tell you that the central set piece of Insurrecto involves a revolution. Their respective scripts in hand, Chiara and Magsalin embark on a road trip from Manila to the island of Samar, where a massacre took place during the Philippine-American War. Whether the Balangiga Massacre of 1901 refers to the killing of dozens of American soldiers in an uprising by the townspeople or to the American army razing villages, burning crops, and killing thousands of Filipinos in retaliation—well, that depends on your point of view.

The movie Chiara wants to make takes place during the days surrounding this bloody occasion and focuses on two women: the Filipino organizer of the uprising and the white photographer who documents its horrific aftermath. The photographer’s lens—yet another frame—is the opening through which Americans will see the bloody consequences of their distant, oft-forgotten war. But Chiara’s interest in Balangiga—the cause of her “unearned case of white guilt,” as Magsalin puts it—is familial. She is the daughter of filmmaker Ludo Brasi, the creator of The Unintended, an iconic movie of the Vietnam War. Ludo died shortly after the movie was made, and it’s this personal tragedy, not the larger political one, that brings Chiara to the Philippines: though set in Vietnam, The Unintended was filmed in Balangiga.

One country stands in for another, like a stunt double; the war in the Philippines is overlaid with the later war in Vietnam. This brutal elision turns the camera back on the viewer, parsing those who know the difference from those who can’t be bothered to. When Chiara asks Magsalin to meet her, for the first time, at Muhammad Ali Mall, Magsalin is skeptical: “No one in Manila calls the mall by that name.” Chiara’s words brand her a foreigner. Apostol makes tremendous use of the doubled nature of her homeland, invaded and occupied many times over: like secret agents, the streets and buildings and bodies of water all have more than one moniker.

“Choosing names is the first act of creating,” Apostol writes. Her puzzle-box of a book is filled with names both invented and historical: Casiana Nacionales, the real-life revolutionary; Jacob “Howling Wilderness” Smith, the American general whose epithet refers to the order he gave his troops after the Filipino uprising: “The more you kill and burn, the better it will please me. The interior of Samar must be made a howling wilderness.” Even the pop-cultural touchstones threaded through the book’s competing narratives jab and wink at the politics of naming: Muhammad Ali is a name chosen by its wearer, self-created; Elvis Aaron Presley is shadowed by the unused name of his stillborn twin.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-