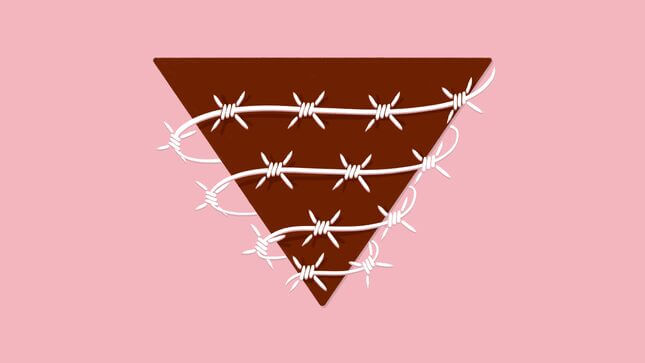

Image: Tara Jacoby/GMG

When I think about my sexual prime, I remember the summer in New York when I was 25, in my first relationship, and on my back screaming as my gynecologist poked around my vagina with a Q-tip.

“Here?” she asked.

I screamed.

“Here?” she asked again.

Another scream.

My whole body was sweating. At one point I briefly blacked out from the pain.

This was the summer I set out to understand why sex hurts.

It had always been this way: a raw, burning sensation any time anything entered my vagina. Even tampons were unbearable.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-