Get in Shape Girl: A Century of Working Out from Home

In Depth

Illustration: Chelsea Beck

My husband emerged from the basement the other day, glowing and incredulous, and exclaimed: “Did you realize you can actually do a whole, legitimately good yoga class right at home?” A one-time college athlete, he used to hit the gym daily. But now, weeks into quarantine, he remains impressed by the endless permutations of downward dog and pigeon pose—not to mention classes from bootcamp to KidzBop cardio—available under our roof. Home exercise is a multi-billion dollar industry with roots a century old, but it’s not so surprising it took being housebound for him to “discover” it, or that my preferred platform, Obé Fitness, has a pastel-pink aesthetic: working out from home has for decades been marketed mostly to women assumed both to spend more time in the house and more energy on their appearance.

It wasn’t always that way. Men were aggressively marketed at-home fitness in the 1920s, when the whole idea of “purposive exercise” began to take hold. As the white-collar sector expanded, (overwhelmingly white) men engaged in “civilized” cerebral work learned they needed to deliberately exercise their bodies. Hours hunched over their desks, they feared, would make them weak, unattractive, and, eugenicists predicted, unable to procreate as fast as immigrants and minorities with hardier bodies and higher birth rates: effectively complicit in “race suicide.” But gyms were few and far between, and were generally considered sleazy gathering spots for men more interested in their appearance—or the company of other men—than appropriately masculine pursuits. Bodybuilder-cum-gym-entrepreneur Vic Tanny reflected that when he opened his first gym in the 1930s, getting men in the door was the biggest challenge. Men were doubly embarrassed: “to expose their potbelly and desire to get rid of that potbelly in a public gymnasium.”

Mail-order fitness was one solution. “Just a few minutes a day” and “no apparatus needed!” promised Charles Atlas, of the “Dynamic Tension” home exercise regime he began marketing in 1929. Atlas laid on the heteronormative masculinity thick, advertising in comic books with promises to beef up effeminate “97-pound weaklings” into real men who could attract beautiful women and beat up any male interlopers who tried to steal them. Any indication men sought aesthetic outcomes, like “banishing such ailments as…pimples, skin blotches, and the others that do you out of the good things and good times in life” was buried in the fine print, for such issues were embarrassingly womanly.

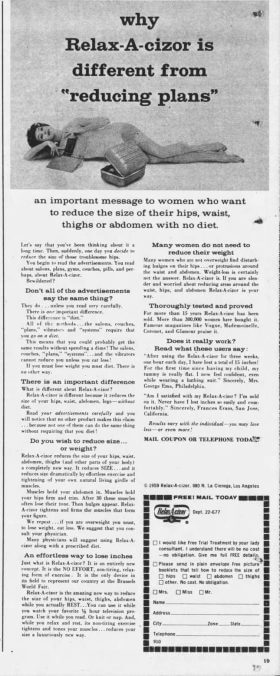

If men had to be aggressively convinced that they should exercise, fitness was far more socially acceptable for women, especially if it was in pursuit of beauty—an acceptable feminine aspiration—not a gateway to brutish sport. Cosmetics entrepreneurs like Helena Rubinstein and Elizabeth Arden built luxurious New York emporiums that offered “passive exercise” for “figure control” alongside skincare treatments. Countless products promised to replicate such miraculous results at home for women who didn’t have access to the high-end spas in New York. “You exert no effort,” declared a 1956 ad for the Relax-A-Cizor. Billed as “the normal, healthy way to pull in inches,” the device was for a “busy woman” who wanted “real exercise,” without the unseemly sweat of “bicycles, massage tables, heat, or massage.” On the contrary: “You use it while you read, rest, watch television… even while you sleep!” No surprise, the Federal Trade Commission register is chock-full of forgotten home fitness devices because so many, from reducing couches to bust-augmenting contraptions, sparked lawsuits.

But nothing established the normalcy of working out at home as much as TV. Between 1945 and 1959, home television ownership exploded from less than ten thousand sets to over 52 million, but exercise TV was no sure thing. When Jack Lalanne pitched studio executives a fitness program in 1950, they scoffed that no one would tune into a television show about exercise, much less set aside whatever they were doing to follow along in their living room. Undeterred, Lalanne launched his eponymous show out of his own pocket. Trimnastics—“I don’t like to call it exercise,” he would say. Millions of homemakers tuned in for his folksy fitness advice, completed with only a chair as equipment and offered as his dog Happy yapped around him. Lalanne soon received heaps of mail from viewers hungry for his expertise. “You know what happens when you have children,” lamented one mother about her spreading hips in a typical missive. In a tough-love tone that became typical over The Jack Lalanne Show’s 34-year run, he first cheerily assured her that “dumpiness” was in no way a foregone conclusion after 40. Yet he also issued a somber warning: only women’s own neglect of their bodies, or “using children as an excuse,” stood between the homemakers who made up his viewership and “the streamlined figure they want so badly.”

For a generation of women taught that exercise was unladylike and even dangerous, Lalanne’s thirty-minute, black-and-white show made the radical proposition of claiming that women should make time for exercise, for their own sake. Contrary to popular belief, he reassured viewers they would not ruin their figures with exercise. Metamorphosis, however, would not come from sitting on the sidelines at their children’s baseball game, or politely listening to their husbands’ war stories. “There’s only one time to start improving yourself and there’s only one time in your life and you know when it is?… NOW. N-O-W. This can make your life or break it,” Lalanne implored. He looked viewers in the eye and said, “You’re an intelligent person.” Biceps exposed, Lalanne boldly rejected ageism: “you know what age means? … Age means absolutely nothing.”

But Lalanne also made clear that looking pretty was inseparable from taking control of one’s life through exercise. “Which One Watches the Jack LaLanne Show?” a newspaper advertisement queried. If the side-by-side photos of women’s backsides identical but for their girth weren’t obvious enough, the copy explained: “the woman who follows the Jack LaLanne Show isn’t hard to spot. She usually has a lovelier figure, a more youthful looking face than other women her age.” He had little patience for those who wished for a new body, but failed to work to achieve it: “… you say ‘Dear God, give me the intestinal fortitude to do something about it.’ Then you get your new body. But you have to do it.” Exercise was becoming a required ritual of ladyhood, and thanks to Lalanne, home provided no solace from such reminders.

Ratcheting up the stakes of failing to exercise paved the way for more such TV. Debbie Drake, a Corpus Christi secretary plagued by “figure trouble” since a scrawny adolescence, launched a weekly television show in 1959. By fall 1960, “the most gorgeous calisthenics teacher in the country” was broadcast nationally on 74 stations, with a syndicated column and book on the way, The Shreveport Journal reported. “Debbie will take you through the wonderful world of exercise, to the land of slim, trim beauty,” assured a male announcer over the opening bars of the show. Drake, who favored leotards accented with a prim collar, an aesthetic equal parts propriety and Playboy Bunny, moved seamlessly from duck-walks to “build up the calves” to neck rolls for double chins, a problem about which “many girls” wrote in. One 1962 profile acknowledged that while most Cold War Americans understood physical fitness was a national security and public health issue, Drake’s motto was all about appearance: “To Make America the Beautiful—Exercise!”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-