National Enquirer Reporters Were So Good at Journalism They Ruined News

Latest

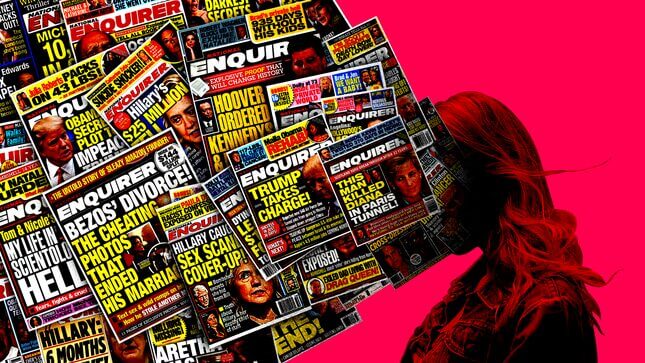

Graphic: Jim Cooke/Image Getty

Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, the National Enquirer graced nearly every grocery store checkout line in America, its lurid headlines just as innocuous a part of the shopping experience as Juicy Fruit gum or a pack of Skittles. In those days, the magazine seemed like the news equivalent of that checkout aisle candy—not sustenance but not dangerous. But just as a diet consisting primarily of sugar can have dangerous long-term health effects, the sensationalizing of the news via Enquirer headlines was a direct contributor to the slow decay of American media.

First, the Enquirer made way for talk shows, like Geraldo and Jerry Springer, where men and women who looked and sounded like news anchors dedicated hours to filling American living rooms with scandal. Eventually, America’s growing appetite for the sensational would birth 24-hour “news” organizations like Fox, where it became normal to shout unverified conspiracy theories into the ether or present a panel of guests who screamed soundbites so loudly over one another it was impossible to make out any salient debate points.

Yet every reporter who ever worked at the National Enquirer is a better journalist than I. This was not a thought I had ever entertained until I watched Mark Landsman’s documentary Scandalous—about the rise of the Enquirer and the tabloid’s lasting impact on the way America gets its news—and then spent two days speaking with former Enquirer reporters Judith Regan and Barbara Sternig. Either could have gotten me to confess to conspiring with Ukraine to hide Hillary’s server, had we stayed on the phone 10 minutes longer.

Regan and Sternig are so good at their jobs that, when speaking with them, it’s easy to forget that their tremendous ability to elicit information wasn’t used to break stories like Watergate. Instead, their unerring skills were mostly used to spin and amplify salacious details until a story had grown so unwieldy it was impossible to tell fact from fiction. The National Enquirer helped normalize news stories like Hillary’s emails—situations that become completely blown out of proportion through exaggerated or outright false information. In Scandalous, Landsman attempts to trace the history of the Enquirer from harmless grocery store confection to Donald Trump’s personal propaganda machine, a path that lowered standards for all news outlets and convinced many Americans that they couldn’t trust the news.

From the outset, Enquirer founder Generoso Pope Jr. hired a slew of crack investigative journalists with either Harvard journalism school training or backgrounds in British tabloid reporting, which was historically much more tenacious than that of its American counterparts. According to the documentary, his family’s mafia connections made him able to pay his reporters salaries and offer perks, like private jets, that most journalists had never dreamed of. For the first time in America, Pope was hiring first-rate investigative journalists to report “soft” news, tailored to an ideal reader he called Missy America. Missy America, much like myself, was interested in celebrity gossip, medical oddities, the supernatural, and true crime.

The results were staggering. In its heyday, every issue of the National Enquirer sold millions of copies, but the real genius was Pope’s distribution plan, which got the news right where we could see it in the grocery store checkout line. Whether or not customers bought it, the contents were disseminated through headlines and teasers; its articles skimmed when lines were too long. The Enquirer gave Missy America access to celebrity that went beyond the polished, posed press releases and canned PR statements of fan magazines, offering glimpses of stars as they “really” were, warts and all. But while the Enquirer was changing America’s relationship with the news and celebrity, Barbara Sternig explained to me that the intense reportage was also changing the ways that celebrities interacted with the media:

“Celebrity journalism used to be fan magazines in touch with PR departments and everyone would make sure all the stories were nice,” she tells me. “With us, it became adversarial.”

Sternig has lots of stories about the glory days of the paper’s rise: being the only woman in the newsroom, flying on private jets to hunt down reluctant celebrities, booking rooms in their hotels to bribe the staff for information.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-